Share this article

WSB: ‘Snotbot’ drones can track whale health and populations

A good drone operator knows fairly well how long a whale stays submerged before it needs to take a breath above water. The flying device isn’t allowed to get within 12 feet of whales without a federal permit, so it buzzes high above the basking cetaceans, in wait.

Just at the right moment, the whale exhales, blowing a mixture of seawater, mucus and other material well past 12 feet in the air. The drone swoops in, collecting the droplets of liquid in special petri dishes attached to the side using Velcro. Mission accomplished. The drone heads back to the researchers controlling it in the boat.

Many kilometers away in a laboratory on land, researchers can now use the small bits of genetic material to determine information about the individual whale, from its identity and family to its health. By gathering material from the proverbial snot spewed forth from the blowholes of several whales, the researchers can make larger determinations about the population health of species like humpbacks (Megaptera novaeangliae) or blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus)—a feat that biologists have struggled to accomplish in the past due to the difficulty in tracking whales in the wild.

“We can use that drone for all kinds of things,” said Shannon Atkinson, a fisheries professor at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks.

In a study published recently in the Wildlife Society Bulletin, Atkinson and her co-authors describe how they are using drones to better track the health and populations of blue whales, humpbacks and even orcas (Orcinus orca) using this technique they refer to as the Snotbot Program.

“One thing that impresses us as lab scientists is how many different things you can find from one exhale,” Atkinson said.

By flying drones above whales from boats, researchers can snap photos of tail flukes to identify individuals with the help of online catalogues put together from various organizations tracking whales.

“It’s sort of like their fingerprint,” Atkinson said.

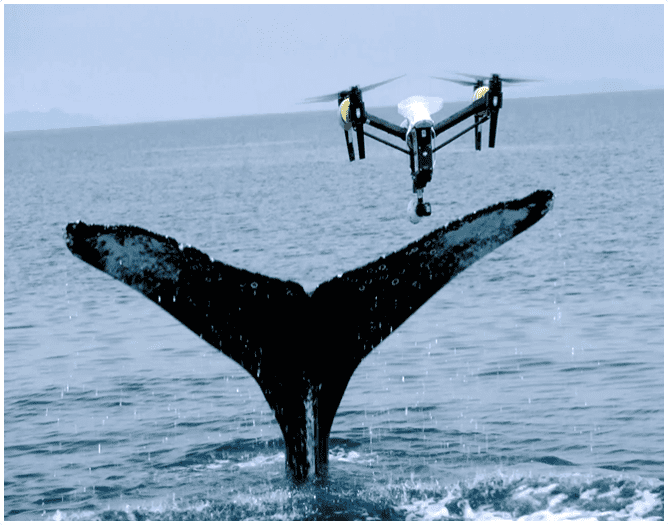

Petri dishes attached to the sides of the drones gather DNA material exhaled by a humpback whale.

Credit: Ocean Alliance, NMFS Permit 18636

Atkinson said the researchers have been able to use the drones along with previous sighting data recorded in a database to track one female humpback from the coast of British Columbia all the way to Hawaii, where it calved.

The material gathered in the petri dishes also contains DNA that can reveal a number of things about whales.

The team can tell what the whale’s sex is, its reproductive history and even if its pregnant. “If you applied it to humans it would almost be kind of creepy,” Atkinson said.

This use of drones is a game-changer for marine biologists, especially since whales travel so far and swim so deep that they are often difficult to track using conventional wildlife techniques.

Atkinson said that other possible techniques to study the mammals include using infrared cameras that can detect the body temperatures of whales. Infrared can also be used to scan whale bodies for injuries from ship strikes.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: A drone flies over a blue whale’s blowhole. Credit: Ocean Alliance, Permit: sgpa/dgvs/00207/17