Share this article

Window decals create sticky situation for deterring bird strikes

Researchers found the decals only work when placed on the outside

People often put decals on their windows to deter birds from striking the glass. But researchers recently found that many of them may be placing them wrong, rendering the decals ineffective.

The most effective way to use these decals, they found, is to place them on the outside of the window, where they are more visible, rather than on the inside.

“A lot of birds die each year because of collisions with windows,” said John Swaddle, faculty director of the Institute for Integrative Conservation. “In the U.S. alone, hundreds of millions of birds die each year from hitting windows. It’s a major conservation problem. We have potential solutions that can be implemented, and individual action can make a difference. So, we are working on various aspects of understanding what solutions are effective and helping people learn about the problem and the solutions and to incentivize action.”

Although producers and vendors tell purchasers that window films and decals should be applied to the outside surface of windows, doing so can be challenging. If the window isn’t at ground level, it could require a ladder—or even a professional’s help. To avoid these inconveniences, some people simply put them on the inside. But researchers weren’t sure how well they would work that way.

In a study Swaddle led published in PeerJ Life & Environment, he and his colleagues conducted a controlled experiment to find out the most useful way to use window decals. “We wanted to simulate a real-world experience for birds, of interacting with windows, while having experimental control so we could isolate the effects of window film products,” he said.

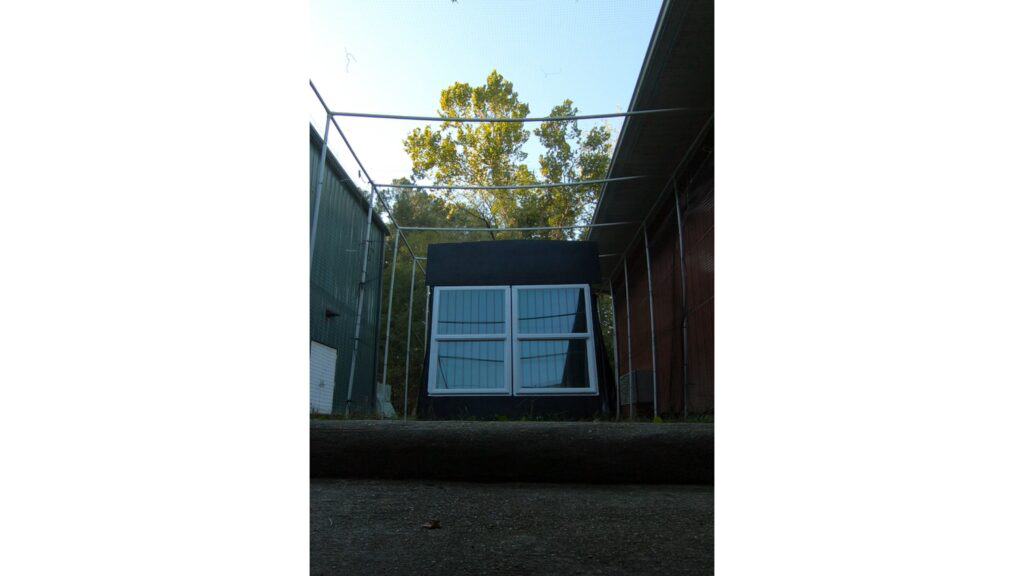

To conduct this experiment, Swaddle and his colleagues built a flight arena and released zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) from a darkened area, so they would naturally fly toward a brighter area. In this brighter area, the team had two windows. In one trial, they tested films from a company called BirdShades compared to a window without a film. In the other trial, they used a product from Haverkamp and another window without a film.

The team tested what the birds would do if these films were placed inside and outside the window. A mist net in front of the windows prevented actual collisions. “We wouldn’t conduct a study that deliberately increased real collisions,” Swaddle said.

The team found that both window film products, which both used different wavelengths of light and different shapes to deter the birds, worked. “That’s good,” Swaddle said. “We believe that both products would be useful in reducing real-world collisions.”

But they found that both films only worked when applied to the outside surface of the windows. They found no benefit at all from films placed inside.

Swaddle suspects that the films are more visible to the birds on the outside because the glass reflects and filters the light. On most modern windows, light would have to pass through two panes of glass to reach decals on the inside of the window, making them less visible.

“Based on our study, we doubt there is much benefit, and we need to help people apply the films and decals more appropriately,” he said.

Header Image: A team of researchers tested how zebra finches pictured here responded to decals placed inside and outside windows. Credit: Stephen Salpukas