Share this article

Wild Cam: Thermal cameras spot roosting birds in the dark

Thermal cameras are helping researchers focus on bird populations while the lights are out.

Birds at roost aren’t always easy to survey due to the darkness and the fact they don’t move around much or make much noise at night. This presents a challenge to scientists intent on investigating roosting behavior.

A team of researchers in Australia wanted to see whether using thermal cameras at night would improve their ability to find elusive birds.

“This has opened the door for us to collect data for a lot of species that have been really difficult to gather data for,” said Will Mitchell, a PhD candidate in biological sciences at Monash University in Melbourne and the lead author of a study published recently in the Journal of Field Ornithology. He and his co-authors were interested in the ecological drivers behind bird roosting. But before they could begin to get at this question, they needed a better way of finding out what species were roosting where. They compared thermal imaging to and monitoring birds by eye during the daytime.

©Will Mitchell

Formerly, Mitchell said, researchers had to attach transmitters to birds then use them to track the birds back to their roosting areas at night after release. Spotlights were also sometimes used, but as this photo shows, they can make it difficult to see some birds, like this white-browed scrubwren (Sericornis frontalis), barely visible amid the branches and vegetation.

©Will Mitchell

Mitchell’s supervisor, Rohan Clarke, had used thermal cameras in the past to detect birds at night in a recreational capacity. Mitchell wanted to see if they would be effective at finding avians while they roost. Although birds spend much of their lives roosting, researchers haven’t always focused much attention on this behavior. But knowing how avians, like these grey fantails (Rhipidura albiscapa), avoid freezing to death or getting eaten during roosting is importing for the conservation of vulnerable species.

©Will Mitchell

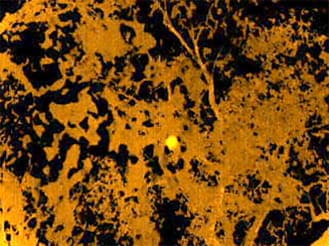

The team found that thermal cameras drastically improved detection of birds at night, as with this yellow-faced honeyeater (Caligavis chrysops), appearing in infrared as a bright golden spot amid a background of orange.

“You feel like the Terminator when you’re in the bush using these things” Mitchell said.

©Rohan Clarke

He and his co-authors spent about an hour at night taking a kilometer-long walk with thermal cameras along 44 transects in the bushland of southwestern Australia. They recorded every bird they saw, such as these laughing kookaburras (Dacelo novaeguineae), caught in the spotlight, as well as the vegetation and the type of roost. Once they found roosts, they measured how visible they were from different directions.

They then walked the same lines during the day, repeating their processes.

The researchers found some limitations when using thermal cameras at night. When roosts were located in areas with clear skies behind them, the cameras often couldn’t handle the disturbance from stars and other sources of light, making it difficult to spot any birds.

They also found that it was harder to detect birds at a distance at night using the cameras than it was spotting them during the day. This, in turn, was confounded by obstacles branches or tree trunks, which can block the thermal heat signature.

But they did discover 22 out of 23 different species commonly found in the study area.

©Will Mitchell

Mitchell said that he and his colleagues were also able to record some rough information on roosting behavior, particularly on how birds balance the need of hiding from predators with that of keeping warm in an area where temperatures sometimes drop as low as 28 degrees Fahrenheit at night.

They were surprised to find that many of the smaller species, such as the eastern yellow robin (Eopsaltria australis), a bird smaller than the American robin (Turdus migratorius), were completely exposed at night, using little buffer against the cold and little protection from predators.

©Rohan Clarke

While it may still be easier to spot birds during the day, some species don’t always forage and roost in the same area, Mitchell said, so surveys that just focus on the daytime could miss the importance of some roosting habitats for vulnerable species.

One example is the plains-wanderer (Pedionomus torquatus), a critically endangered bird representing the only species of its genus, shown here as researchers observed it both by spotlight and by thermal camera. Previous surveys using spotlights hadn’t discovered as many of these birds compared to surveys with infrared cameras.

“It’s going to be a good technique for locating and monitoring these really cryptic and skulky species,” Mitchell said.

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Joshua at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image:

A group of splendid fairy wrens (Malurus splendens) are viewed by spotlight as they roost at night.

©Rohan Clarke