Share this article

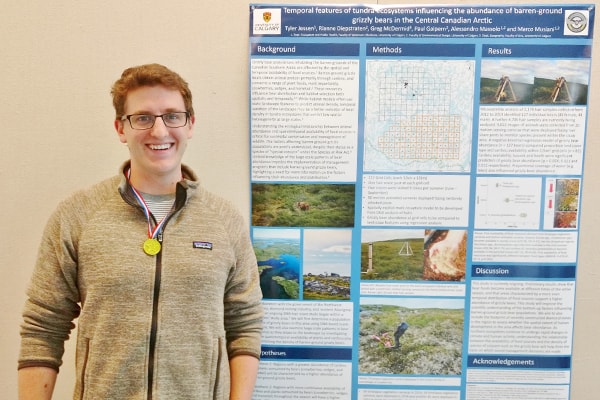

Wild Cam: Student poster winner tracks Arctic grizzlies

The largest populations of Arctic grizzly bears are sustained by a healthy balanced diet of food sources, according to research.

“The idea would be that we could really show that there are areas that are really important for bears,” said Tyler Jessen, a Ph.D. student in veterinary medicine at the University of Calgary and a member of The Wildlife Society. Jessen tied for first place in the Ph.D. category of the student poster competition at TWS’ 2015 Annual Conference in Winnipeg.

While the main staples of grizzlies (Ursus arctos ssp.) in an area around 185 miles northeast of Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories are caribou (Rangifer tarandus), berries and young grasses, the timing when these resources are available and the areas where they pop up can differ greatly. Jessen and poster coauthor Rianne Dietstraten — a master’s student at the University of Calgary — used camera traps and hair snags to track how bears use these resources and the land that contains them in an effort to figure out how grizzlies use the land and food available to them.

To show how the work was done, we used some of the camera trap photos, a time lapse video and other photography to illustrate life in a remote part of Canada for our latest entry in the Wild Cam series.

©Tyler Jessen

The study area was around 185 miles northeast of Yellowknife in more than 10,000 square miles of terrain around the tree line, a transition area where Arctic tundra takes over from taiga terrain. This shot is taken at the beginning of fall in mid-September south of MacKay Lake from one of the helicopters that carried Jessen and his coauthor to the study areas. “It’s the very first snowfall,” Jessen said. “At this point grizzlies are trying to pack on calories and fat.” Within a month, they would likely be in their dens.

©Tyler Jessen and Rianne Dietstraten

The researchers set up 100 camera traps and 217 wooden tripods with barbed wire to snare grizzly hair, which they use to extract DNA and identify individual bears. To attract the animals, Jessen said they used a lure made up of a rag soaked in scents to match the seasonal diets of the bears. The smells, which included fish oil, rotten cow blood and berry essence depending on the time of the year, can be picked up by bears from miles away. Here, you can see the mother bear rubbing her cheek on the barb wire. “They seem to like these things. They almost seem like play toys for them,” Jessen said.

©Tyler Jessen and Rianne Dietstraten

But bears aren’t the only animals with a keen sense of smell for the lure. The traps also attracted wolverines. “They are very elusive but we sure do get a lot of shots of them in our camera traps,” Jessen said. Exactly how they interact with the bears on the landscape is less understood.

Video credit: Tyler Jessen

This time lapse was taken from motion activated camera trap photos. “These bears are exhibiting the exact behavior we want from the bears,” Jessen said. “The rubbing motions and rolling around on the ground leave excellent hair samples for the genetic analysis. As the bears scratch themselves on the barb wire, small bits of hair are removed. The roots of the hairs (where tissue is still present) are where the highest quality DNA samples come from.”

©Tyler Jessen

The helicopter pilot, contracted by a diamond mine to help with research, and an aboriginal community member help to put up a hair snare post in the Northwest Territories. Jessen said that the collaboration between various stakeholders was vital for the success of the project. The color of the sky is due in part to smoke in the atmosphere from fires that burned that year (2014).

©Tyler Jessen and Rianne Dietstraten

The camera traps also captured shots of muskox (Ovibos moschatus) herds. “Many animals will come to check out the hair snare posts but it’s really only the bears which will rip it up,” Jessen said.

Adult muskox, which don’t hibernate or migrate, aren’t usually part of grizzly diets, though bears have been observed eating muskox carcasses. The large herd animals will form protective circles around their young when grizzlies threaten them.

©Tyler Jessen

Caribou form one of the three major sources of food for grizzlies, but they only frequent the study area during their northward or southward migrations in spring and fall. This individual, seen near Aylmer Lake, is likely from the Bathurst Herd, which has seen drastic declines over the past 15 years.

©Tyler Jessen

Spring over the Arctic tundra, when bears are just emerging from hibernation. During this time, the bears eat a lot of young grass. This early grass is higher in protein at this point than it is later in the season, when bears feed more on the berries that ripen in mid-summer. Jessen said the researchers used 80 time lapse cameras aimed at different kinds of vegetation to figure out when they became ripe or available. Areas that had large levels of both of berries and young grass as well as caribou during the fall and spring, seemed to sustain the highest grizzly populations and may be the best areas to conserve from future development interests.

©Tyler Jessen

This bear was being monitored by wildlife officials at a local mine site nearby. “It was being monitored to make sure it wasn’t coming into the mine. That’s the kind of intervention that we hope doesn’t happen because it can be dangerous to people and it can be dangerous to the bear.”

Part of the reason the study was conducted was to see what kind of land bears prefer. A better knowledge of prime grizzly habitat can lower potential conflicts between humans and bears in development areas. Jessen said that knowledge over what makes the best grizzly habitat can be used by land planners when deciding what areas to cede to resource companies. “The diamond mines are the most major industrial activity in the area,” Jessen said.

Image courtesy of Tyler Jessen.

Jessen stands in front of his winning poster at the TWS 2015 Annual Conference. The study is also important, he said, as it can help to track how climate change may affect grizzlies if it means the timing and availability of their food resources changes. “We are also looking at what sorts of landscape and climatic features might influence the development of the plants to determine how climate change might influence plant development,” he said.

This photo essay is part of an ongoing series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project and have photos you’d like to share, email Joshua at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image: A pilot exits a helicopter near the western edge of the study area. ©Tyler Jessen