Share this article

Wild Cam: Scavengers reduce brucellosis risk in elk, moose and cattle

The best way to eliminate brucellosis-infected remains before they can infect nearby moose, elk or cattle may be simple: just eat it.

Brucellosis is a major problem in western states. The point of transmission for the disease often occurs when infected elk (Cervus canadensis) or bison (Bison bison) abort their fetuses. When other elk, bison or even cattle come into contact with these carcasses, they can become infected themselves. Cattle that contract the disease often are euthanized.

The transmission of brucellosis has become a point of contention between conservationists, who want to see more elk or bison on the landscape, and cattle ranchers, who are concerned about the threat to their livestock.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Wildlife managers currently employ a number of strategies to control the spread of brucellosis, such as vaccinating bison and hazing or harvesting elk near ranchlands. But new research on scavengers in Montana shows that animals like coyotes (Canis lantrans) and eagles provide an important service to cattle ranchers and wildlife managers by quickly clearing infected dead animal remains.

“It was cool to see that there already was a tool on the landscape to help clean up and reduce that risk,” said Kimberly Szcodronski, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and the lead author of the study published recently in Ecosphere.

Enlarge

Credit: Torrey Ritter

Szcodronski and co-author Paul Cross, also with USGS, set out to learn more about how scavengers feed in different kinds of environments. They placed cow fetuses that were brucellosis free on three different kinds of landscapes in southwestern Montana. They aimed trail cameras at 264 of the dead animals from February through June in 2017 and again in 2018, on private land (80% of cameras) and on U.S. Forest Service land (20%). They collected about 250,000 photos from 233 camera placements.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

The researchers were initially surprised at the scavengers’ promptness in finding and eliminating the carcasses. Across all habitat types and on private and public land, the fetuses were removed in an average of 3.6 days. The animals worked fastest in grasslands, which saw a 2.9-day average removal, and slowest in sagebrush habitat, where it took scavengers about 5.4 days to eat. In forests, it took an average of 5.2 days for the feast to end. Szcodronski said the fast removal on grasslands likely has to do with better visibility, which especially helps avian scavengers home in on animal remains.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Land management also impacted the speed of scavenger removal, they found. Both ranches and Forest Service land have mixtures of grasslands, sagebrush and forested areas. The researchers found that tissue remained on the landscape the longest—an average of 6.5 days—on ranches that lethally removed scavengers like coyotes.

Forest Service lands saw the fastest removal at 3 days, while carcasses on ranches that tolerated scavengers were gone in 4.1 days on average.

Szcodronski and her colleagues were surprised by the quick removal on Forest Service lands, as they expected that hunting that occurs there might reduce the activity of some scavengers. But the research shows that perhaps the Forest Service land is big enough that hunting doesn’t have a major impact on limiting scavengers.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

The cameras revealed a number of species stopping to eat. Coyotes, red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), ravens (Corvus corax), turkey vultures (Cathartes aura), red-tailed hawks (picture above, Buteo jamaicensis) and crows all ate the remains the researchers placed out.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

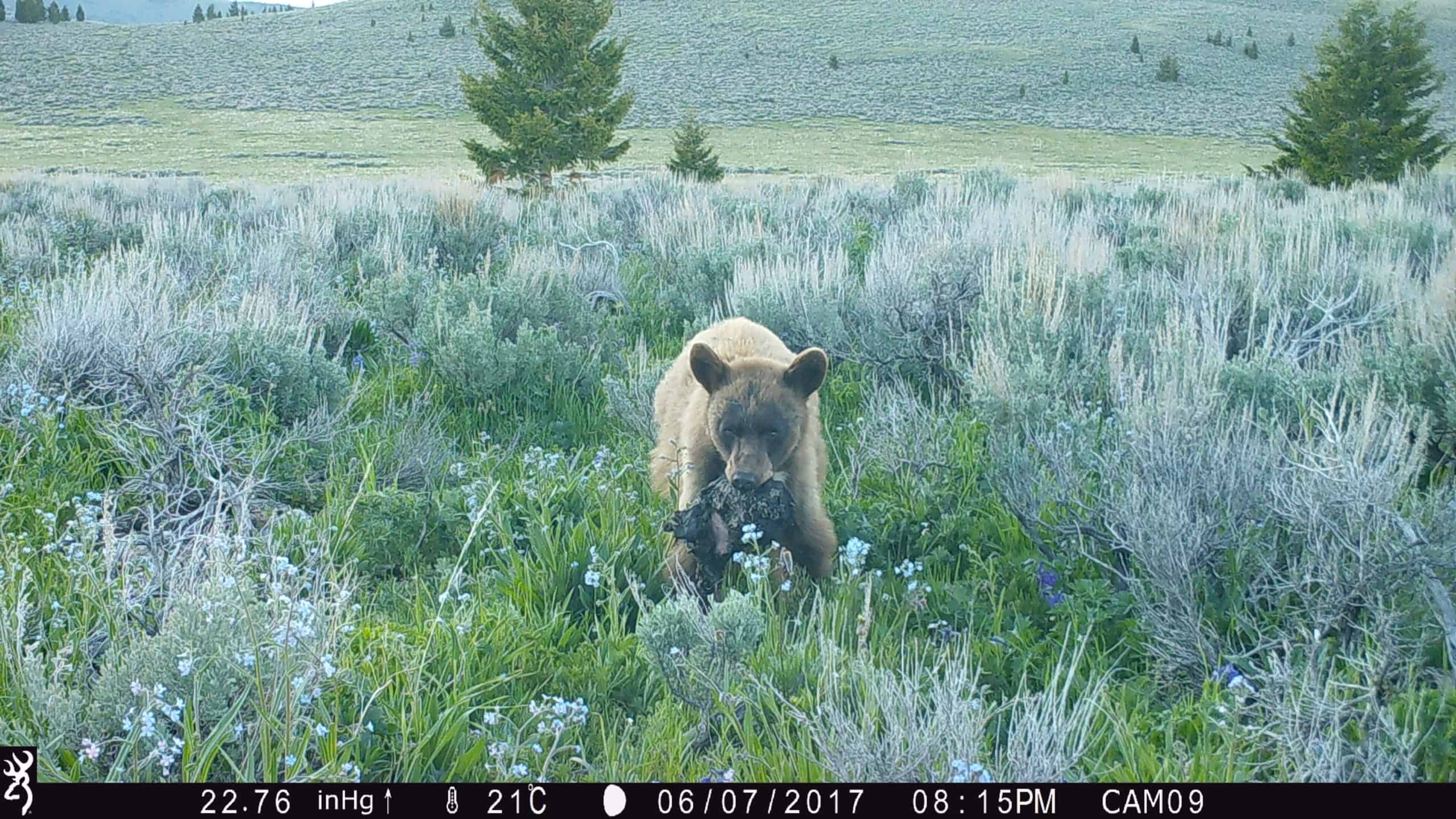

Other large mammals like wolves (Canis lupus), cougars (Puma concolor), grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis), bobcats (Lynx rufus) and black bears (Ursus americanus) also showed up occasionally but didn’t consume as much of the carcasses.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Overall, birds did the most work, contributing 55% of the cadaver removal.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Coyotes and golden eagles consumed the most carcasses, each removing about 24%. Those two species combined accounted for nearly half of the scavenging services.

“In cases where scavengers are unlikely to be a carrier of a disease, they can provide an important ecosystem service of removal of carcasses on the landscape that might harbor disease,” Szcodronski said.

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

She added that even though the ranches that focused heavily on removing coyotes, and sometimes foxes, for the fear that they might prey on their cattle had among the slowest cadaver removal, 6.5 days is still pretty quick. Especially considering the time that it would otherwise take to remove the threat of disease transmission.

“Brucellosis can remain viable on the landscape for weeks to months depending on the conditions,” she said. “[The study] shows that scavengers are really great cleaning agents. They take those risks off the landscape a lot sooner than they would be [removed] without scavengers.”

Enlarge

Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

She also noted that while ranchers might have reasons for removing coyotes, a focus on improving habitats for eagles and reducing the use of lead ammunition on their land may help speed up the removal of carcasses infected with brucellosis.

Enlarge

Credit: Torrey Ritter

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Josh at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image: Coyotes and ravens eat cow fetuses scientists placed out as part of an experiment to determine if scavengers reduce brucellosis risk. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey