Share this article

Wild Cam: Island spotted skunks may need protection

Ellie Bolas has been sprayed by skunks more times than she can remember — several times right in her face. But the experiences haven’t dissuaded her in her mission to learn more about island spotted skunks, even if the aromatic animals themselves don’t necessarily appreciate her efforts. Found only on two of California’s Channel Islands, the squirrel-sized skunks have an array of defensive behaviors that Bolas, a PhD student in ecology at the University of California, Davis, and her colleagues have become intimately familiar with. Before resorting to spraying, an alarmed skunk will stomp its feet and rise up on its front legs.

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

“It’s pretty amazing when you release it, and it does a handstand at you,” Bolas said. “All of these are signals telling you to back off.”

Island spotted skunks (Spilogale gracilis amphiala) are only found on Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz islands, where they are the less famous land-based predators. Most research has focused on the six island fox (Urocyon littoralis) subspecies — each endemic to an island of the archipelago off the coast near Los Angeles. Some of the subspecies are considered threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, but although the skunk is even rarer, it has received less attention.

“The Channel Islands are an incredibly rich place for biodiversity,” Bolas said, and supporting two endemic carnivores on such small islands is rare. But the skunks “have kind of been forgotten,” she said. “The island fox has gotten so much attention.”

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

She and her colleagues set out to learn more about the island skunks, partly since wildlife managers capturing foxes as part of monitoring programs had noticed a decline in accidental skunk captures since 2009.

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

Researchers weren’t sure if this was representative of an actual decline or due to the fact that fox capture methods just weren’t that suitable for capturing skunks. Island spotted skunks are difficult to monitor due to their cryptic nature. Apart from the skunks that turn up in her traps, Bolas has only ever run into a free skunk in the wild once. The species is largely nocturnal, and despite their infamous defense technique, they aren’t easy to sniff out unless they have recently sprayed, Bolas said.

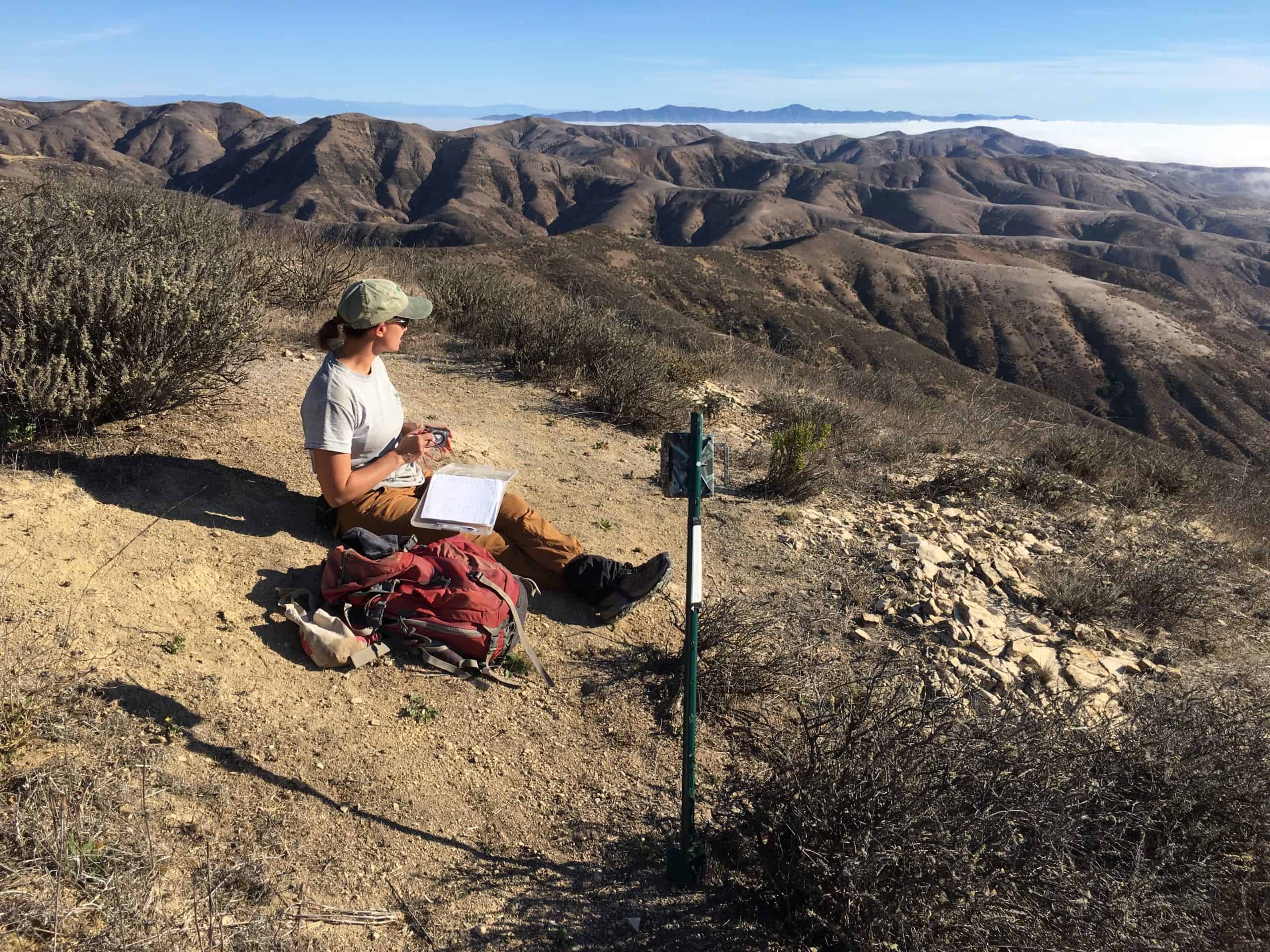

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

Starting in 2016, the team began deploying wildlife cameras like the one above on both Santa Rosa (pictured) and Santa Cruz islands near areas where the types of baited cage traps used for foxes were set. Bolas and her team were looking to better understand the best ways to track the small skunks.

“The big picture here is one of the major things we need to do in conservation biology is to learn how to effectively monitor rare species, because otherwise how are we going to conserve them?” Bolas said.

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

Trapping wild skunks can come with risks for Bolas and her colleagues. “They’re tiny, and they’re fierce,” she joked.

The researchers put them in plastic bags to block the spray when possible, but the spotted skunks’ spray has different toxins than their larger cousins on the mainland, striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis). While removing the smell of the latter can be a trial, Bolas said, a long shower can get rid of the smell of island spotted skunk spray.

“Thankfully my roommates on the island also work with skunks,” she said.

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

After analyzing the photos and traps, they discovered that both monitoring techniques — camera traps and fox traps — revealed similar numbers of skunks. They reported their findings in a study published recently in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

“That gave us a lot of confidence that either traps or camera monitoring are good techniques,” she said.

There were some differences, though. Cameras that operated into the fall showed an increase in skunk detections as compared to either method during the summer, meaning that fall may be the best time to get an accurate idea of numbers.

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

Yet both techniques turned up skunks less than 1% of the time, suggesting island spotted skunks may be rare on both islands. Similar methods detected the plains spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius interrupta) on the mainland less than 1% of the time, Bolas said, and it is a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act.

“That gives us an indication that this is a species that needs some conservation attention,” she said.

Conserving the skunk is important because of its role in the larger ecosystem of the islands where it lives. The skunks are one of the only two land predators for rodents, lizards and other species, and create burrows that may be used by other species.

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

They also appear to interact with island foxes, which Bolas is currently analyzing for future publication. The two have been coexisting for at least the past 7,000 years or so, and may compete for some of the same food. While the foxes usually come out on top, she’s seen instances of skunks chasing foxes off.

“Sometimes the island skunk also wins,” Bolas said.

Enlarge

Credit: Ellie Bolas

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Joshua at jlearn@wildlife.org.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: Santa Cruz Island plays host to two mesopredators. Credit: Ellie Bolas