Share this article

Watch: Afraid of change? Try returning rare mynas to the wild

Learning about neophobia—or the fear of new things—can help researchers figure out how to contribute to bringing back a bird species that’s nearly extinct from the wild in Indonesia.

Only about 50 Bali myna (Leucopsar rothschildi) remain in the wild. But some zoos have built captive populations of the species with the hopes of introducing them back into their natural environments. Researchers wanted to learn more about the birds’ behaviors to help ensure they survive after being reintroduced.

“All of us encounter novelty all the time,” said Rachael Miller, a biology lecturer at Anglia Ruskin University in England. “For both humans and other animals, it impacts almost everything we do.”

Miller had initially looked at how corvids like ravens and crows responded to new things. Corvids are quite neophobic, she found, and there is a social and developmental aspect to their neophobia as well. Just as children may respond similarly to their parents in facing new things, corvids were also influenced by their social environment.

But when she was a zookeeper about 10 years ago, the Bali myna always stuck out to her because of how endangered they were. She wanted to find out about their fear of new environments and foods once reintroduced. “Suddenly, they’re out there in the wild, and we want these animals to survive,” she said. “So if we can learn about their different responses to neophobia in captivity, we can pull that into techniques to use to increase their survival rate when they’re reintroduced.”

In a study published in Royal Society Open Science, Miller and her colleagues conducted experiments in three different UK zoos, including Waddesdon Manor, Cotswolds Wildlife Park and Gardens and Birdworld, to see how Bali mynas responded to new situations. In one experiment, they created objects of different colors and textures that the birds had never seen before so they could study what happened when they placed the novel object next to a food bowl. “It was a fun arts and craft experience, sticking things together,” she said. In another, they placed jelly—a novel food that’s even a little weird for humans—next to their food bowl and recorded how long it took them to eat their food compared to normal conditions. And none of them ate the jelly.

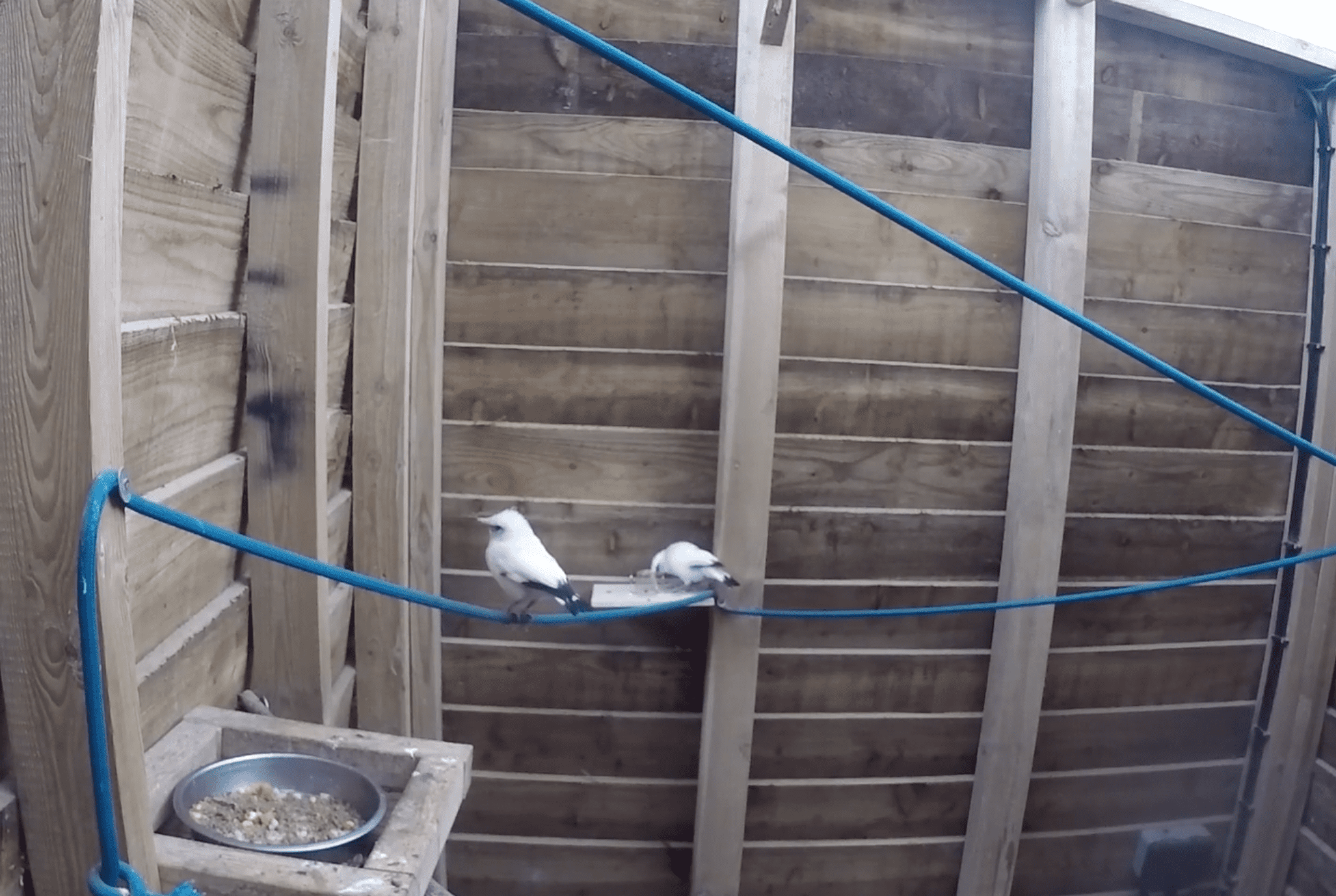

Bali mynas work on solving a task for a reward. Credit: Rachael Miller

The team found that age plays an important role. Juveniles approached the food much faster than adults. “This reminds me of children,” Miller said. “They tend to go through these developmental stages of not having a lot of fear of things.”

The team also provided some problem-solving tasks, including having to remove lids or cups to get to a worm underneath. They found that the birds that went to the food bowl more quickly were also the quickest to solve these tasks.

They also noticed that the Bali mynas behaved differently with other species present in the aviary. If the other species was a competitor, like a white-spotted laughingthrush (Lanthocincla bieti), and it tried to take food the Bali myna wanted, the myna was less neophobic than if the other species wasn’t a competitor, like Edward’s pheasant (Lophura edwardsi).

“It seems like you need to go quickly to get the food when there are competitors around, though not if these other species are non-competitors,” Miller said.

Miller hopes some of these findings can help reintroduction efforts. For example, juveniles might be better able than adults to adapt to the new environment. Social groupings may also be important.

It’s not just mynas, she said. Miller believes behavior should be considered alongside genetics and other factors when returning species to the wild.

“What I hope will start to come from this work is an openness to starting to use more behavioral and cognition research within conservation applications, such as in pre-release training and individual selection for release,” she said.

Header Image: Juvenile Bali mynas are less scared of new objects than older mynas are. Credit: Gavin Harrison