Share this article

Warming climate may have ushered moose into Alaska

Moose recovering in the Arctic may be benefiting from higher shrubs than were present in the past 150 years, according to a new study.

“If you’re a moose you’ve got to be near those shrubs both for forage and for cover from predators,” said Ken Tape, an assistant professor and ecologist at University of Alaska Fairbanks and lead author of a study published yesterday in PLOS ONE.

But the warming climate seems to be affording shrubbery north of the tree line in Alaska to grow higher, which may be ushering in a growing moose population in the state.

“Moose were actually absent from the tundra in the early 20th century,” Tape said. But today, around 200,000 of the animals can be found in the state, many of them in the tundra.

Tape and his coauthors set out to determine whether higher shrubs they had witnessed were one of the reasons behind this population explosion. A previous study they conducted looked at how moose populations and shrub may have changed since the 1960s, but this work took them back another century.

They built a relationship between the amount of warmth in the summer and the average shrub height across northern Alaska. “Shrubs really respond sensitively and rapidly to increases in temperature,” he said.

Once they had numbers on this, they could apply known temperature information back to around 1860. They estimated that the shrubs were shorter in years past, around a meter in height.

“From our data, it looks like the habitat wasn’t there 150 years ago,” Tape said. “If you put [a moose] in a one-meter shrub patch, he’s sticking out like a sore thumb.

During the winter, shrubs less than 1.25 meters tall are probably not tall enough to stick out of the snow and provide the moose with something to eat. Tape said they could find no evidence of moose browsing with low shrubs — otherwise they usually find browsing marks.

Way back when

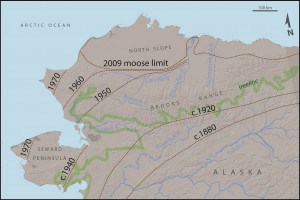

This image shows changes in moose distribution (dashed lines) in northern Alaska since 1880. Shrub plots were distributed along the Chandler and Colville Rivers (orange ellipse), and temperature records were derived at two locations therein (gray dots). The green line represents the tree line. ©Tape et al.

Tape says that this data shows that overhunting didn’t cause the disappearance of moose in Alaska, though it’s difficult to know what happened before the 1850s: “The data gets really murky really fast.”

The first evidence of moose in Alaska turned up around 12,000 years ago — around the same time humans first showed up on the archaeological record. But no moose bones were found in the state’s north from between 3,000 and 9,000 years ago. From 3,000 years ago up to the present, there is at least a sporadic moose presence — a fact that leads some to point to the possibility of overhunting leading to the animals’ extirpation in the area within the past few hundred years.

Tape says the arrival of guns is a possible explanation for this disappearance, and the subsequent decline of indigenous people in the north eventually allowed the species to come back.

But Tape and his coauthors’ study shows that the habitat likely wouldn’t have supported moose, at least 150 years. He says that he’d like to look at the population dynamics in a longer term in future studies to understand more about the driving factors between these population fluctuations.

But in the meantime, he says the larger issue at stake is that the moose may be indicators of the shifting climate across the whole tree line.

“The moose are really telling us what’s changing.”

Header Image: A bull moose in tundra shrub habitat in Denali National Park and Preserve in Alaska. Image courtesy of Ken Tape.