Share this article

Virus discovered infecting bald eagles

Researchers recently discovered a virus infecting bald eagles across the country.

The virus is a member of the hepacivirus genus, the same genus of viruses that cause hepatitis C in humans. Until recently, it was not known that this type of virus could infect a bird.

Biologists discovered the new virus as they sought the mystery cause of the fatal Wisconsin River Eagle Syndrome — which affects eagles along the river in southern Wisconsin. Scientists have known about the syndrome for about 20 years, but no one could figure out what caused it.

“The typical story is someone — a member of the public or a scientist out in the field — sees an eagle that’s stumbling, falling over, seizing, vomiting or just in really bad shape,” said Tony Goldberg, a professor at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “The eagle isn’t starving or thin, but it looks really sick. Someone would rush it to the nearest rehab or veterinary clinic, but it would die on the way or soon after.”

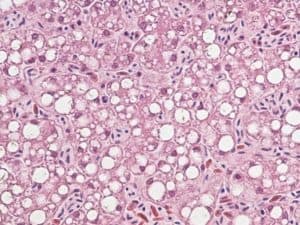

A microscopic image of bald eagle liver that died from Wisconsin River Eagle Syndrome. The white spaces are tissue damage characteristic of the disease. ©Marie Pinkerton

Post-mortem exams showed liver cells with big holes in them. Scientists began suspecting that a toxin or pesticide may be involved, but investigations turned up nothing. Others suspected a link with West Nile virus which was known to cause neurological symptoms in eagles and kill them, but that was also ruled out.

That’s when Goldberg, the lead author of a recent study published in Scientific Reports, got involved. “My lab specializes in identifying the causes of mystery diseases in wildlife,” he said. “We use new technologies for virus hunting. We began working with the USGS National Wildlife Health Center to investigate some of their most frustrating unsolved disease cases. Wisconsin River Eagle Syndrome was at the top of the list.”

Bald eagles in Wisconsin are nine times more likely than eagles in other states to have hepacivirus. ©UW-Madison

The National Wildlife Health Center, also based in Madison, Wisconsin, provided Goldberg and his colleagues with data and samples of eagles that had died from the syndrome as well as other eagles across the United States. After processing the eagles and conducting their virus hunt, “out popped this entirely unexpected virus,” Goldberg said.

The team also noticed that the liver damage looked similar to the end stages of hepatitis C infection in humans.

“At this point, we were ready to pop the champagne corks because we suspected that we’d solved the mystery of the syndrome,” Goldberg said. “But not so fast. It’s never that easy.”

Wisconsin eagles weren’t the only ones affected, they discovered. Eagles as far away as Florida and Washington state also had the virus, although Wisconsin eagles were about nine times more likely to have the virus than eagles elsewhere, and those along the Wisconsin River were 14 times more likely to be infected.

Wherever eagles live close to humans they suffer human-induced causes of death, such as being shot, hit by cars or electrocuted by power lines, Goldberg said. He speculates that the virus may weaken birds and make them more likely to frequent urban areas where scavenging opportunities may be greater but where the dangers of living near people may also be higher.

The next steps are to look at the prevalence of the virus in healthy eagles and to follow infected eagles over time to see if they appear weak.

“Bald eagle hepacivirus is not a slam dunk,” Goldberg said.

Despite the diseases, eagles continue to rebound from their declines that began in the 1960s due to the pesticide DDT. “But it’s easy to get complacent and stop looking,” he said. “We don’t want to ignore eagles and say, ‘They’re fine. We can leave them alone now.’”

Goldberg said this is just one confounding disease that has been showing up in wildlife recently. “We’re seeing diseases emerge in species that are really important to our culture and that affect our health indirectly,” he said. “This may be the tip of the proverbial iceberg.”

Header Image: Researchers discovered a virus in bald eagles related to hepatitis C in humans. ©ThreeIfByBike