Share this article

Vast online data stores are treasure troves for ecologists

The Tour of Flanders is one of the most prestigious cycling events in the world. The Belgian bicycle race is broadly and closely watched globally. But while sports commentators are analyzing every turn of the athletes competing in the race, ecologists are now looking at the background.

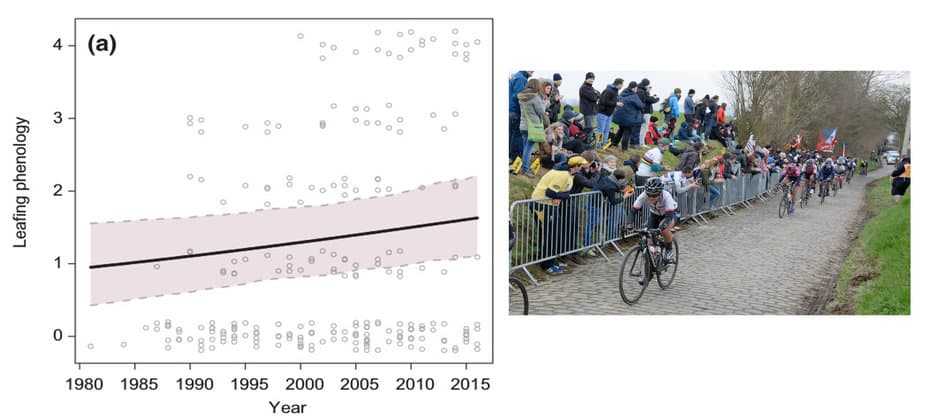

Since the race has occurred at the same time and in the same area every year since roughly 1913, scientists realized that by watching the trees along the route over the decades, they had an accurate record of how climate change was affecting the timing of their bloom.

Researchers tracked changes in bloom times of trees based on archived media videos of the Tour of Flanders cycling race.

©S. Yuki.

A growing number of scientists are starting to delve into this type of data — information that wasn’t collected with ecology in mind but could present a wealth of free information.

The new field of potential research, referred to by some as iEcology, involves using any of the vast number of online resources to answer ecological questions. Some researchers have used Facebook photos people posted of fearsome looking tarantulas to identify previously unknown species in South Africa. Others have tracked geotags on social media photos to determine some of the most popular parts of natural areas for tourists.

“There will probably be many more things we haven’t thought of here,” said Ivan Jarić, a scientist at the Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences and the lead author of a study published recently in Trends in Ecology and Evolution that reviews some of the possible uses of the expanding field.

Jarić said the frequency and amount of data being generated is astounding. “More than eight hours of YouTube videos are posted every second,” he said.

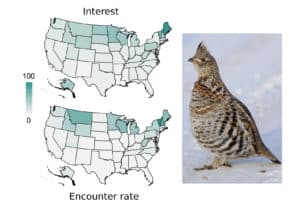

Researchers found a correlation between ruffed grouse encounter rates and Google searches for the bird based on Google Trends. ©D. Faulder

Meanwhile, NASA satellite images can contain all kinds of information about forest cover, and technology like Google Street View or geotagged Flickr images can reveal the presence of wildlife.

While citizen science includes hobbyists knowingly gathering information on things like wildlife distribution, iEcology is made up of data collected from people who may not know they are even helping or programs not intended for scientific research. But the two forms of data collection can be used together. For example, geotagged photos from Flickr or Google Street View can be included in the citizen science app iNaturalist, a program that has algorithms that can sometimes identify wildlife species by photos.

“I’m really curious to see over the coming years what directions we could go,” Jarić said, adding that potential ecological uses of collected data will only improve as machine learning algorithms improve.

He said that he doesn’t believe iEcology will replace traditional fieldwork, but it can be used to bolster it. Some researchers used information tracked by Google Trends to find that common searches of many bird species such as ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) on Google matched well in geographic location to where these birds are known to occur in the United States. The discovery shows that Google Trends could help scientists better determine where to focus their research.

Plus, Jarić noted, many of these online data tools are free and easy to access — even for scientists on lockdown.

“It’s the perfect tool for these lonely days of home offices,” he said.

Header Image: Cycling fans watch the Tour of Flanders for the action, but biologists turned their attention to the trees. ©VISITFLANDERS