Share this article

TWS2020: Hot on the slow trail of Panama sloths

They may seem lazy and move at the pace of 2020 election ballot counting, but sloths are pretty quick to react when they feel threatened.

“They can bite and swing their arms extremely fast — you won’t even realize it,” said TWS member Chelsea Morton, a graduate research assistant at the Cooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory and Forestry Program at Southern Illinois University under the advisement of Clay Nielsen. She should know. Morton has been bitten twice by sloths at the Panamerican Conservation Association facility, which works to rehabilitate sloths — mostly orphans — affected by deforestation in Panama.

Enlarge

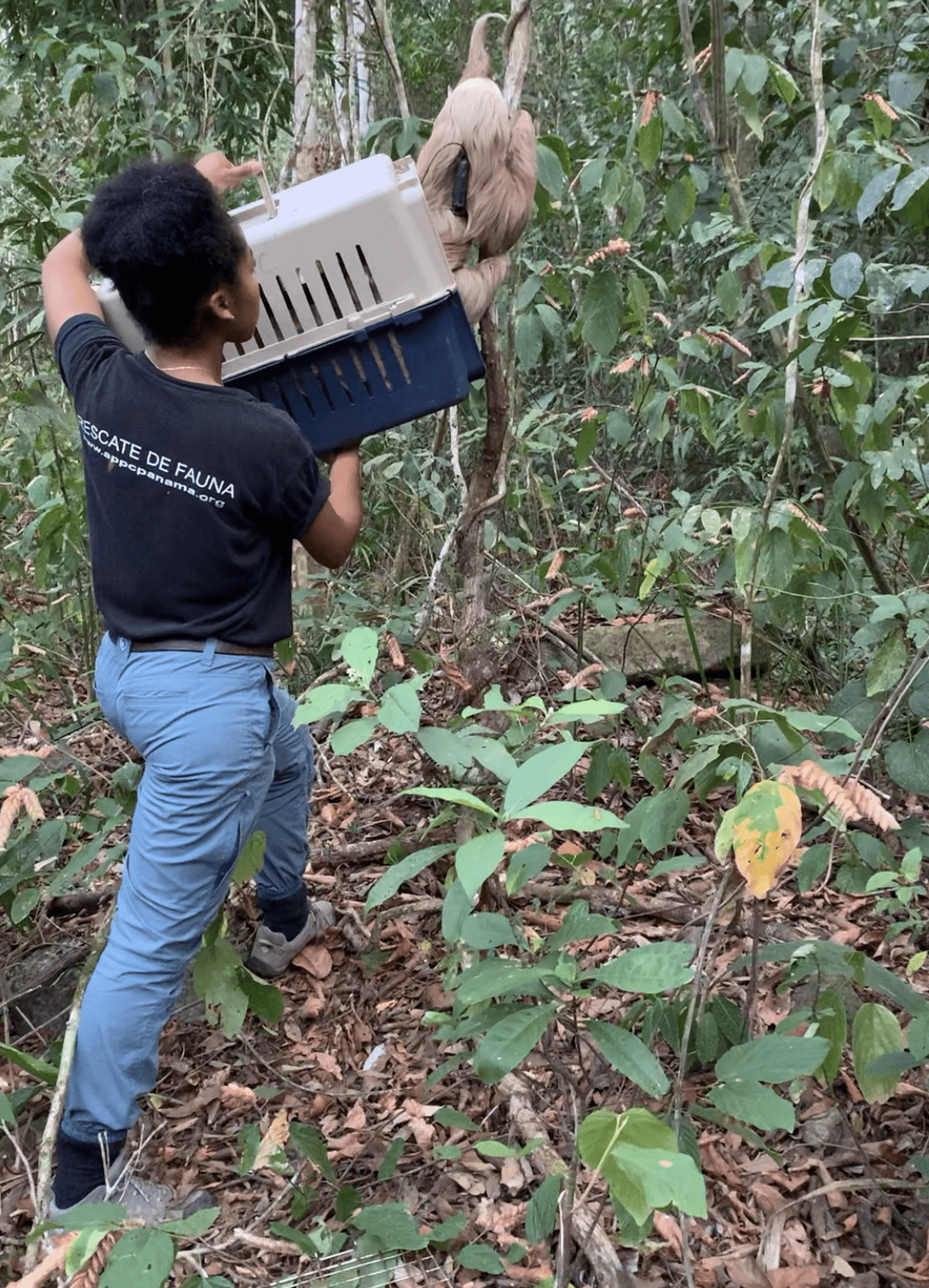

Credit: Panamerican Conservation Association.

“They’re just not in the mood sometimes — they don’t want to be bothered. They aren’t cuddly like some people think,” she said.

The numbers of orphaned sloths are increasing as development picks up in the Central American country. Morton has volunteered with the organization since 2015, but she wondered what was happening to the animals after they’re released. In ongoing research presented in a poster at The Wildlife Society’s virtual 2020 Annual Conference, she and her colleagues tracked 10 Hoffmann’s two-toed sloths (Choloepus hoffmanni) using VHF telemetry devices attached to the animals by backpacks in central Panama.

They began their fieldwork in October 2019 when some of the animals were placed in a soft release pen, a group of trees surrounded by a fence to separate them from the canopy of nearby trees. Orphan sloths in the area are typically raised in captivity until they are old enough to wean off milk. When they can eat the leaves that adults rely, they’re put into these pens.

Enlarge

Credit: Chelsea Morton

Morton and her colleagues observed behaviors of the sloths for the three months they spent in the soft release pen, before being set free about 300 meters away at Soberanía National Park.

So far, the VHF devices have revealed that most sloths have very small home ranges — not surprising given their infamous pace. Morton said that the sloths typically rely more on hiding — she once walked by a single individual she was tracking for five days before finally seeing it wrapped up in a ball of vines. “They are actually really hard to find,” she said. “They are very elusive and can hide themselves if necessary.”

In fact, the animals often don’t even move much beyond where they are initially released, Morton said.

They also become more nocturnal over time and seem to adapt to new foraging conditions, eating plants they didn’t eat in captivity.

Enlarge

Credit: Panamerican Conservation Association

Of the 10 animals they followed, some have been predated, possibly by weasel-like tayras (Eira barbara) or ocelots (Leopardus pardalis), so the animals seem to be doing well after rehabilitation.

Work on studying the sloths after rehabilitation is ongoing. But Morton said that finding out if these programs work is important, since the animals are more vulnerable to habitat loss and development due to their slow pace — it’s not as if they can just run away when they hear a chainsaw. She hopes the continuing work will help reveal ways that rescue centers can take better measures to ensure survival.

This research was presented at TWS’ 2020 Virtual Conference. Conference attendees can continue to visit the virtual conference and review Morton’s poster for six months following the live event. Click here to learn about how to take part in upcoming conferences.

Header Image: A sloth in a rehabilitation center in Panama. Credit: Chelsea Morton