Share this article

Translocating young Hawaiian monk seals improves survival

Shifting young Hawaiian monk seals from their whelping beaches to safer areas free of sharks and the threat of entanglement in marine debris may improve survival for the endangered marine mammals.

“We had way higher survival than would have been expected if they had just stayed at their native sites,” said Jason Baker, a marine biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Services and the lead author of a study published recently in Animal Conservation.

Hawaiian monk seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi) are listed under the federal Endangered Species Act due to declining food resources, shark predation, male aggression, entanglement in fishing nets and habitat loss, among other threats. Only about 1,400 individuals remain, occupying the Hawaiian Islands and occasionally turning up in Johnston Atoll, about 800 miles southwest of Hawaii.

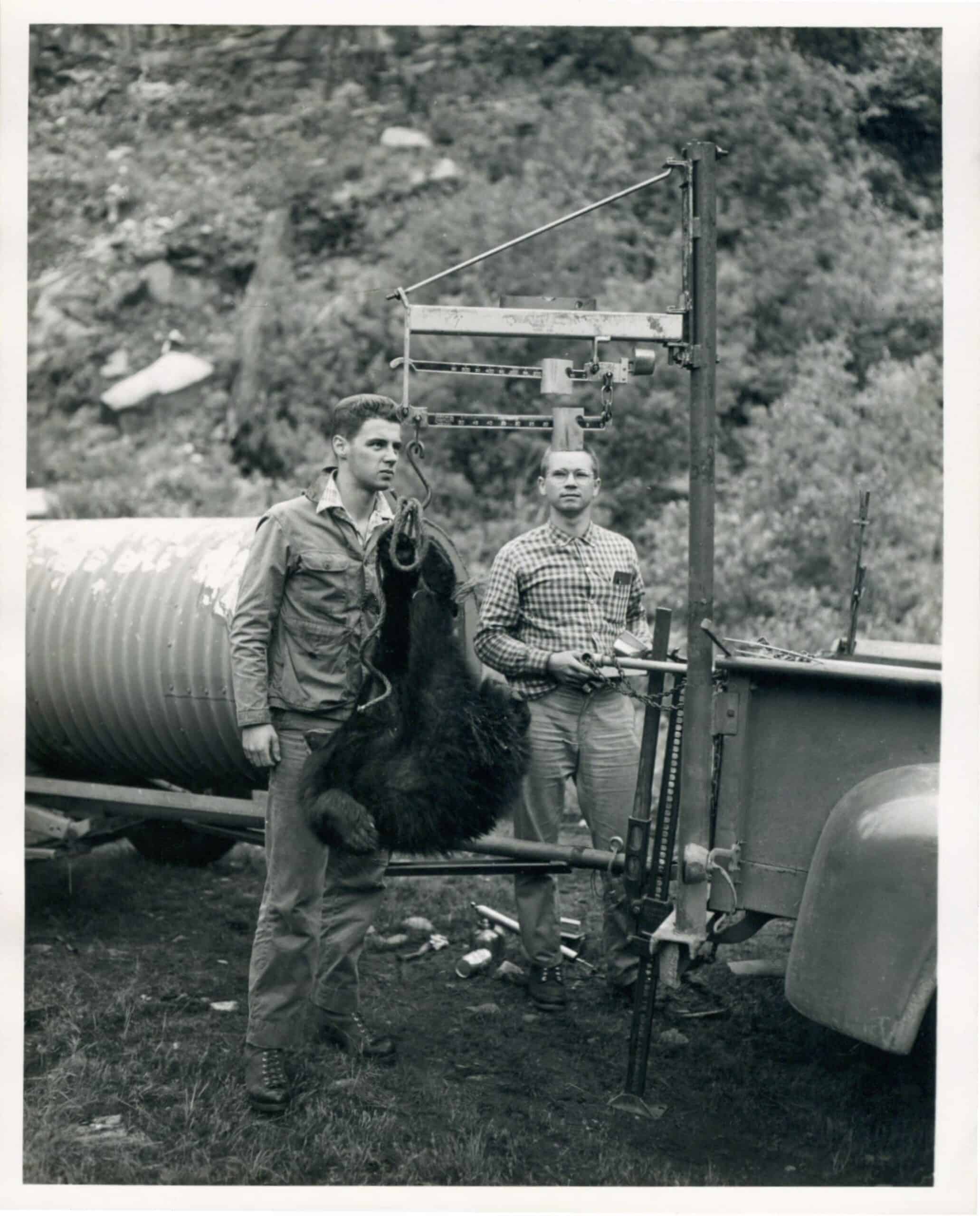

A seal captured for translocation gets transferred to a small boat. Credit: NOAA

Monk seal mothers usually abandon their well-fattened pups on the beach about five to seven weeks after birth. The weaning pups remain mostly on the beach for over a month living off fat stores, gradually increasing their forays into the water. The seals are most vulnerable during these first few swims, when it’s easy for sharks to pick them off.

In an effort to boost survival of young seals during this vulnerable weaning period, wildlife managers translocated pups among islands and atolls within the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, placing them at sites that were safer from threats

“Weaned pups are at the best age at which to do an intervention like this to do an intervention like this,” Baker said. Translocating older animals doesn’t work as well, he said, since they often try to return to where they were born. “Translocations are pretty rarely used in marine mammals.”

Young translocated monk seals wait in a pen just before re-release. Credit: NOAA

Baker and his colleagues analyzed survival of the pups released on the new beaches and compared it to the survival of pups left on their birth beaches. Initially, they found little difference between the two groups, but when they took a closer look at the pups themselves, they found that when they accounted for how fat the pups were when they had weaned (a factor already known to be related to survival chances), the boost in survival due to the translocations was significant.

Of 13 female seals they studied, researchers would have expected only one to survive on the more dangerous beaches. But after translocation, seven survived. In 2019, one of the survivors already has had a female pup.

“This demonstrates the compounding interest of being able to save females,” Baker said. “Females are the ones that are really going to provide long-term benefits.”

Header Image: Only about 1,400 Hawaiian monk seals remain in the wild. Credit: USFWS