Comparison between two wildlife species detection methods—trail cameras and environmental DNA in soil—has revealed that the former is still superior, in most cases. But eDNA techniques can still be beneficial.

“Rarely is there a one-size-fits-all survey technique to capture all the animal diversity out there,” said Sasha Tetzlaff, a research biologist at the Construction Engineering Research Laboratory of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Tetzlaff and his colleagues were working on detecting populations of imperiled reptiles in the lower northern peninsula of Michigan. They set up trail cameras to capture photos of these species during the spring and summer of 2021 in front of drift fences at sites on the Camp Grayling Joint Maneuver Training Center, a nearly 60,000-hectare National Guard base. They also took soil samples by the camera and drift fences three times during this period—once in spring, once in mid-summer and once in late summer to early fall.

In the surveyed sites—including grasslands, wetlands and a mixture of coniferous and hardwood forests—they didn’t detect any of the reptile species in the trail camera images or using the eDNA analysis. But their data didn’t go to waste. The team decided to look at the species they did detect using both techniques, which included birds and mammals.

Trail cameras versus eDNA

The team analyzed hundreds of thousands of trail camera images in a study published in Ecology and Evolution. They also analyzed the soil samples using a general assay that can detect vertebrates and identify species.

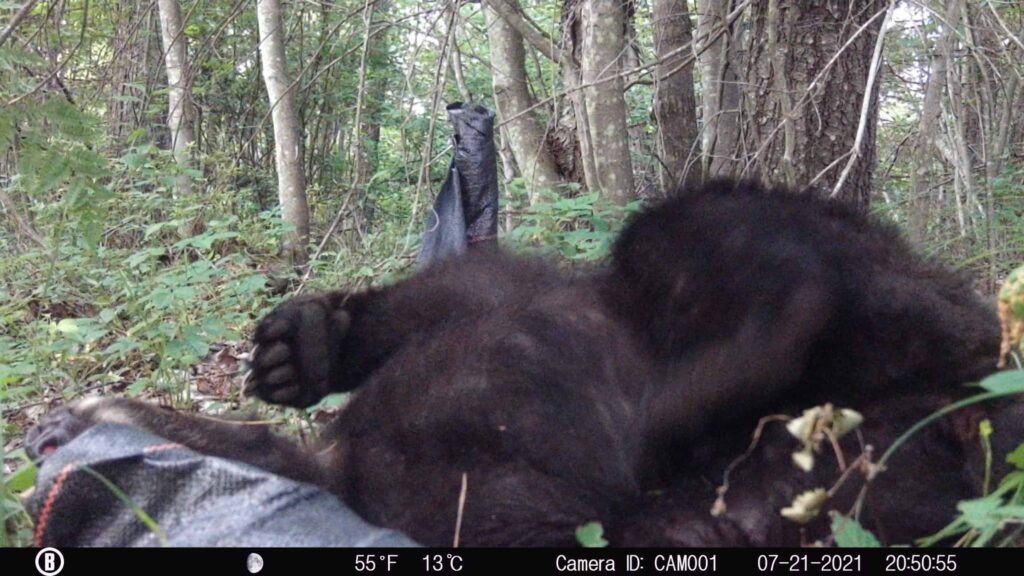

Mammals like bears (Ursus americanus), raccoons (Procyon lotor) and bobcats (Lynx rufus) were typically detected only on camera.

Environmental DNA likely didn’t detect species like bears because while they may shed a lot of DNA at once through poop or hair, they also move around a lot and don’t spend much time in a single area, Tetzlaff said.

Mammals like white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) and squirrels were detected using both cameras and eDNA analysis.

But eDNA detected some smaller mammals like shrews, lemmings and voles that the cameras didn’t always pick up—either because they were too small or not mobile enough to trigger the motion-censored cameras.

Can eDNA surveys detect birds?

For birds, the cameras were much better at detecting species than eDNA. This is likely due to their flitty nature—the images revealed the birds using the drift fences to perch, but they didn’t spend much time in one place—likely not enough to deposit significant amounts of DNA on the soil.

The exceptions to the trend in birds were larger species like sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis) and ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) that spend more time on the ground. Environmental DNA techniques were equally or more effective at detecting these species compared to trail cameras.

Because the researchers didn’t detect any reptiles by camera or eDNA, they are now attempting the survey again using an upturned bucket outfitted with a trail camera—a technique that’s gaining popularity for capturing footage of small animals.

Overall, Tetzlaff said the study reveals that trail cameras detected more species than soil eDNA analysis, but the latter still boosted the overall number of detections. For example, the cameras—but not the soil analysis—detected two species that were previously not recorded at Camp Grayling: bobcats and a Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), while the soil analysis revealed one species never before detected in the area and not seen in the photos: the star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata).

“[Soil eDNA] is not a replacement for other survey techniques,” he said. But he still sees this newer technique as adding exciting new possibilities to enhance surveys.

Article by Joshua Rapp Learn