Share this article

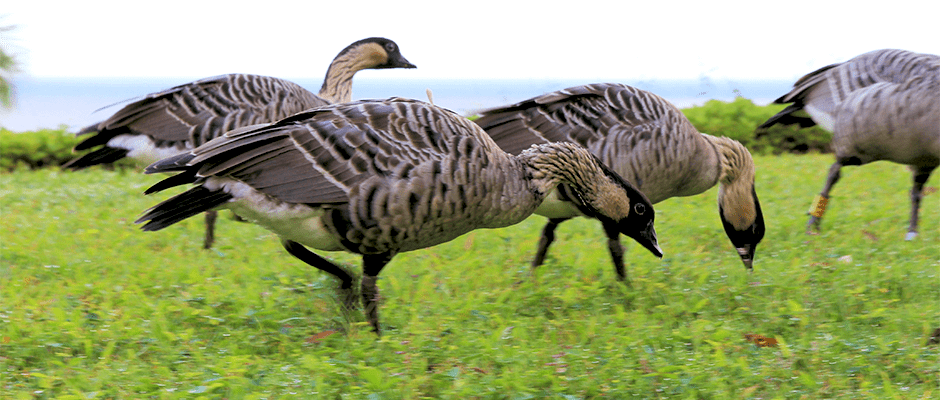

Toxoplasmosis parasite widespread even in healthy nene geese

Hawaii’s native geese may be too big for cats to hunt, but that doesn’t mean they are safe from the invasive predators. Parasites spread by cat feces kill about 4 percent of all nenes (Branta sandvicensis) — more than any other type of infection. Now, researchers have found that the parasite Toxoplasma gondii is widespread even in geese that appear healthy.

“There are so many feral cats here in Hawaii that I figured, if you’re seeing animals dying from the disease, then there’s got to be a larger number of animals that are infected but haven’t been killed by the parasite,” said Thierry Work, a wildlife disease specialist with the U.S. Geological Survey and lead author of the study recently published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases.

The nene — also known as Hawaiian goose — is the state bird of Hawaii, and like many native species endemic to the islands, it is threatened with extinction. To find out how widespread T. gondii is in nenes, the researchers sampled blood from 94 birds on three Hawaiian islands, and tested it for T. gondii antibodies. Animals never fully get rid of T. gondii, so it’s safe to assume that any goose with antibodies is infected, says Work.

On the island of Molokai, 48 percent were infected; on Kauai and Maui, infection rates were 21 and 23 percent, respectively. Molokai, the site with the highest infection rate, also had a particularly large cat population, although the sample sizes were too small to tell whether the difference between islands was meaningful.

While researchers have documented toxoplasmosis in dead wildlife in the past, few have looked for it in animals that appear healthy, says TWS member Chris Lepczyk, a wildlife ecologist and conservation biologist at Auburn University, who has worked on the feral cat problem in Hawaii and was not involved in the new project.

“Not all animals are symptomatic,” he said. “By doing blood draws, you have a better sense of exposure in the whole population.”

T. gondii could potentially kill nenes not only through acute illness, but by changing their behavior, the researchers suggest. The parasite in its dormant form causes no obvious symptoms, but there is evidence that it increases seemingly risky behaviors. For example, infected rodents lose their fear of cat urine, making them more likely to become a feline meal. This is bad for the rodents, but good for the parasites, which need cat hosts to complete the sexual phase of their lifecycle. Many nenes are killed by hazards such as cars and predators, and there is no telling yet whether T. gondii contributes to these casualties, according to the researchers.

While the full impact of T. gondii remains unclear, the new study is enough to raise concern, both for nenes and for other animals that share their contaminated environment, says TWS member Dave Jessup, a wildlife veterinarian who has studied T. gondii in other species and was not involved in the project. Animals become infected either by eating meat from infected animals, or by eating the oocysts (eggs) that cats expel with their feces. Nenes don’t eat meat, so in their case, infections presumably come through the latter route.

“[Infection] is the result of some sort of direct contact with the oocysts from cats, which are likely getting into the water supply,” he said. “That means a lot of other species are at risk.”

Header Image: Many nene geese that appear healthy are infected with Toxoplasma gondii, a behavior-altering parasite spread by cat feces. ©WiseTim