Share this article

The Return of an odious invader — from The Wildlife Professional

Cooperation to conquer screwworm and protect Key deer

Imagine happening upon an animal through a cloud of flies and the smell of decay, its body full of wriggling maggots as it walks around. Although this may sound like a scene from a science fiction story, it’s not.

Resembling the common housefly, the New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) possesses one terrifying difference: the fly’s larvae consume live flesh, entering through any small wound that has broken the skin. The maggots tunnel under skin through muscle tissue and enlarge the wound, attracting more flies to lay eggs. An untreated infestation can kill the host within two weeks.

Although eradicated from the U.S. in the 1960s, a recent screwworm outbreak infesting endangered Key deer (Odocoileus virginianus clavium) meant that the odious invader was back. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists made the grim discovery when the subspecies of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) began dying off in and around Key Deer National Refuge in the Florida Keys.

To protect American agriculture and preserve the iconic deer, emergency action was needed. Managing the threat required the coordinated and cooperative efforts of federal, state and local agencies to quickly contain the destructive insects.

Eradication of a killer

The New World screwworm, likely of South American origin, moved into North America by the early 1800s. With no way to control it, the livestock losses from the insect cost producers from Florida to California millions of dollars annually by the 1930s.

After an intensive research effort by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the agency launched a national eradication program in 1957 that relied upon the mass release of sterilized male screwworm flies. The infertile flies were incapable of producing offspring with wild female flies, resulting in a rapid and species-specific population decline. The new control strategy — known as SIT for sterile insect technique — was successful in less than 10 years and resulted in the eradication of screwworms from both wildlife and domestic animals.

Given the huge losses screwworms can cause, the USDA extended the eradication program beyond the southern U.S. border to reduce the likelihood of its return. With the help of foreign cooperators, USDA’s agency, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), worked to eradicate the insects from Mexico and Central America. By 2001, the effort was successful, providing an extensive buffer zone for the U.S. as well as protecting cooperator countries.

Today, USDA’s international screwworm program maintains the spatial buffer as a precaution. Along with the Panamanian government, it co-sponsors the sustained release of 20 million sterile flies per week in the Darién Gap — a remote region along the Panama-Colombia border (USDA, 2017) — to help prevent the otherwise inevitable return of the screwworm flies. In case of an outbreak, the program’s facility is also prepared to ramp up production levels to provide many more millions of sterile insects.

Despite this intensive program, sporadic screwworm reinvasions in the U.S. have always been a possibility.

Return from exile

USDA International Services raises sterile male flies as part of its sterile insect technique. When released, they prevent production of offspring with wild females. ©USDA Wildlife Services

In July 2016, USFWS staff began noticing a strange sickness in Key deer on Big Pine Key. Closer inspection revealed their ghastly condition — many animals had open wounds infested with flesh-eating maggots.

Biologists scrambled to identify the cause. Coordinating with entomologists at the USDA and the University of Florida, USFWS sent samples to the agency’s lab for analysis. On October 3, 2016, USDA epidemiologists publicly confirmed an active outbreak of New World screwworms in the Florida Keys — the state’s first in 50 years. A quarantine zone to reduce the chances of the outbreak spreading was quickly established on the island.

APHIS was prepared for just such an event. It supports a highly trained staff that is ready to respond to outbreaks. The team hit the ground quickly once the quarantine was announced, implementing a screwworm emergency action plan developed years before and regularly updated with new information on methods and risks.

Mobilization

In addition to the USFWS and USDA, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, and Monroe County—where the Keys are located — stepped up to participate. Each agency brought its own specialized expertise and personnel to the outbreak zone. A unified incident command center was set up to coordinate the efforts and help ensure consistent leadership.

Dozens of USFWS taff from other parts of the country came to support the effort. They worked out of a second command center focused on the deerprotection efforts at the refuge and community efforts.

Close inspection of potential infestations and progress of past treatments was possible while hand-feeding medicated bait to habituated deer on Big Pine Key. ©USDA Wildlife Services

USDA sent a team of first responders from its Wildlife Services, Veterinary Services and International Services programs. The eight wildlife disease biologists from the National Wildlife Disease Program, Surveillance and Emergency Response System had a history of working together and experience with incident-specialized wildlife management situations. Their regular duties include tracking, monitoring and removing urban deer populations; and they have specialized training to deal with wildlife disease events — a combination of talents ideally suited for heavily developed parts of Big Pine Key.

Their public outreach experience also proved to be invaluable. Beyond working with the deer and cooperating agencies, the biologists also coordinated with a network of several hundred citizen volunteers committed to saving their beloved Key deer.

When the team arrived, they found that mammals other than Key deer had been infested with screwworms. The discovery led Florida agriculture officials to immediately quarantine the Florida Keys and establish a mandatory checkpoint on Key Largo, the gateway to the Florida peninsula. A check point was set up to inspect vehicles for live animals to ensure no infested animals inadvertently left the area. USDA and Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services veterinarians at the checkpoint would ultimately inspect 16,902 animals during the quarantine.

Sterilized fly release began as quickly as USDA’s Panamanian facility could boost production. The first shipment reached the Keys on October 10, only seven days after the outbreak was officially declared. Over the course of the eradication effort, over 150 million sterile flies would be released in the affected areas.

Saving an endangered species

Livestock feed troughs — shortened and outfitted with rollers containing an antiparasitic drug — created self-medicating stations for remote and more wary deer. ©Kate Watts, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

In the late 1940s, only 50 Key deer were left. Now with a population of about 1,000 animals, they were still considered critically endangered. The outbreak occurred during the rut season, which meant bucks with open wounds were the primary casualties. The team knew, however, that control and eradication before fawning was especially critical because of the potential impact on does giving birth and justdropped fawns.

While every effort was made to save the lives of infested animals, some were too far gone; and field staff needed to make tough decisions and humanely kill individuals to prevent further suffering and limit the spread of infestations. USFWS and Florida Wildlife Commission veterinarians treated mild and moderate wounds whenever possible. But first, the deer had to be found and captured.

WS staff supported this mission, conducting regular patrols while responding to public tips to a USFWS hotline. Their target response time to a possible infested animal was 15 minutes or less. On location, they maneuvered close enough to view possible wounds through binoculars. Depending on the nature of the wounds and the animal’s behavior, veterinarians were called in to treat the animal. Using their experience in tranquilizing and handling large animals, WS biologists also supported the field treatment activities, assisting the veterinarians in on-the-spot surgical procedures that ultimately saved many infested deer. The team removed the maggots, cleaned and dressed the wounds and marked the animals before releasing them. These treatments were all accomplished in the field, often under difficult conditions on dark, swampy terrain or in view of the concerned public. Decisions on how to treat screwworm-infested deer were often difficult. Some in obvious extreme stress and pain with baseball-size holes in their flesh — signs of advanced muscular and vascular damage — had to be humanely killed. Lethal removal of an animal is always a difficult decision, but even more so given the public’s strong emotional attachments to many individually recognizable deer. Discharging a firearm in populated areas also leaves no room for error. In these situations, WS biologists carefully evaluated their options and guided the affected animal to an appropriate area where they could fire a single, effective shot from a suppressed firearm. Each decision prioritized conducting lethal removal in a safe, humane, and publicly acceptable manner.

The Incident Command formulated a plan to help prevent additional infestations. Biologists and volunteers treated deer preemptively by hand-administering feed containing Doramectin, an anti-parasitic veterinary drug. It was also administered therapeutically to mildly infested individuals. Some deer living in populated areas of Big Pine Key had lost their fear of humans, so they readily took the feed.

In instances where a small herd contained one or two lightly infested individuals needing medication, understanding deer behavior was important. WS biologists drew upon their experience with urban deer in order to manipulate the herd in a way that allowed feeding the targets without causing the group to flee.

Most affected Key deer, however, inhabited the trackless wilderness of the National Key Deer Refuge — about 9,200 acres of multiple undeveloped islands composed of a mosaic of salt marsh, brackish wetlands, dense tropical mangrove and rocky pine forests. Tracking the deer through these areas was futile. Biologists could only catch a glimpse before the skittish animals disappeared into the mangroves. A better approach was needed.

For the refuge’s inaccessible backcountry, incident managers devised a passive treatment system adapted from USDA Veterinary Services’ fever tick work with cattle in Texas. USFWS set up Doramectin-coated rollers in front of feeder stations, forcing the deer to rub against the rollers as they ate. Twenty-seven stations spread across multiple remote islands served as the main method to administer the drug to remote populations.

Innovative tactics

Wildlife Services wildlife disease biologists Jay Cumbee and Wes Gaston work with a veterinarian and biologists from the Florida Wildlife Commission and USFWS during field treatment of an infested buck. ©USDA Wildlife Services

Once everything was in place, the coordinated eradication tactics started working. Between the release of sterile flies, treatment of infested animals and dispersal of medicated feed, severe screwworm cases declined. In a single month, the team’s priorities shifted from euthanasia to treatment, and then to monitoring and verification.

By late November, WS biologists confirmed that treated animals were healthy. These previously captured and tagged deer now served as “live sentinels.” They created a sentinel deer list and checked each animal at least every other day to ensure they remained maggot-free, a sign that the antiparasitic treatments were working and flies were not reinfesting the animal.

The team also took another unconventional approach to preserving the endangered deer. With its perilously small gene pool, each death represented not just the loss of an individual, but a major deletion from an already limited amount of genetic diversity. To help preserve the pool, biologists collected semen from dead male deer for breeding efforts should it become necessary for survival of the species. They also collected tissue samples to test for chronic wasting disease and blood to test for other pathogens that could, if missed, one day threaten the deer.

Unconditional surrender

On January 6, 2017, USFWS humanely removed the last screwworm-infested deer on Big Munson Island.

Wildlife Services wildlife disease biologist Wes Gaston prepares the anti-parasitic Doramectin for bait before feeding to the deer. ©USDA Wildlife Services

But that same month, an affected animal outside the quarantine area turned up near Homestead, a town near the tip of Florida and over 70 miles from the original outbreak zone. USDA officials verified screwworm as the cause of infestation in the stray dog, which was quickly isolated and treated locally. The implications, however, were dire, and highlighted the risk of the flies spreading beyond the Keys.

The origin of the dog’s infestation could not be determined, a major concern for officials. To protect against further spread of the flies, the interagency team launched a monitoring effort and expanded the release of sterilized male flies to the Florida mainland. The quick identification and response to this anomaly so far outside the target management zone demonstrated how public education efforts across and outside Florida worked to limit the invasive pest’s spread and impact on other communities.

On March 23, only five months after the outbreak was confirmed, the agency declared that screwworms had been eradicated in Florida.

The toll had been heavy on the endangered Key deer: 135 deer were killed by the screwworms or euthanized due to an advanced infestation. The outbreak had killed well over 10 percent of the estimated 1,000 Key deer. In 2016, USFWS began a collaring and telemetry project to help assess the impacts on the deer population. It also plans to continue passive monitoring via trail cameras indefinitely (Parker et al 2017).

Keeping a watchful eye

The swift interagency effort to eradicate the New World screwworm may have saved the Key deer from extinction in the wild. With a narrow range and small gene pool, the population likely would not have survived the loss of many more individuals during the outbreak.

Six months later, the species faced another threat — a direct hit by Hurricane Irma in September 2017. With its population already smaller, the beloved deer might not have walked out of the storm’s devastation if not for coordinated interagency action to wipe out the odious invaders.

This real-life story of a potentially devastating invasion of a tiny endangered deer ended well, thanks to the readiness and specialized training of an interagency team that came together to safeguard our country’s wildlife resources.

Learn more

For more information on screwworm eradication and response, see the USDA Story Map and Investigation into Introduction of New World Screwworm into Florida Keys and these two reports, Florida Key Deer Screwworm: Final Report Phase 1 (Fall 2016) and Phase II (Spring/ Summer 2017).

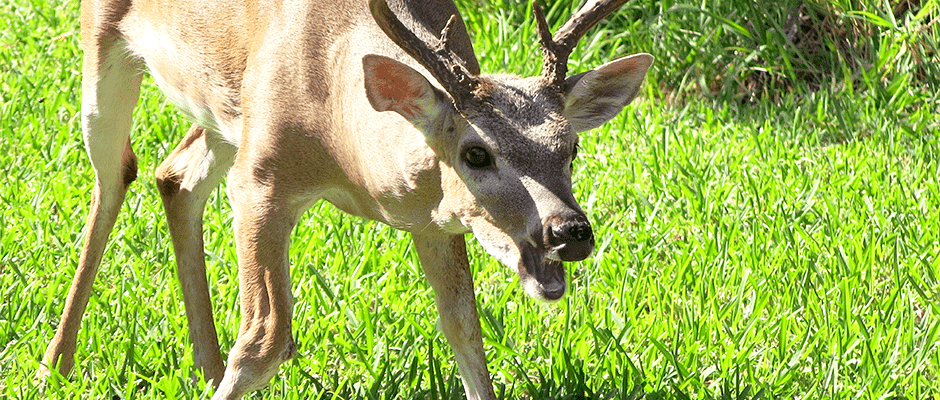

Header Image: A Key deer with an apparent mild infestation of New World screwworms at the base of its right antler is coaxed in for treatment. ©USDA Wildlife Services