Share this article

Road salt leads to bloated wood frogs

A growing body of evidence suggests that the road salt used to melt snow on highways, roads and sidewalks in northern areas is trickling into the environment, affecting both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Too much salt can kill some organisms, but it can also have secondary effects on wildlife, such as making frogs more susceptible to disease.

Now, research shows that road salt may be causing wood frogs (Rana sylvatica) to bloat in New England wetlands, which can have consequences for their populations.

“Some of them looked like water balloons, like someone poked a needle in and pumped them up,” said Steven Brady, an assistant professor of biology at the Southern Connecticut State University and the lead author of a study published recently in Freshwater Biology on the wood frogs. The bloating mostly occurred on the sides of their bodies, and just under the skin on their upper legs.

An egg-laden female migrates across a road at night to a breeding pond. Credit: Steven Brady

Brady and his colleagues examined 38 wood frog populations across New England, comparing the amphibians alongside roads with populations a few hundred meters away.

They found way more bloated wood frogs within 60 feet of roads than in wetlands farther away. The bloated frogs eventually do lose this extra water, they found, but, in areas along the road, it takes longer.

Brady and his co-authors aren’t sure exactly why the salt is leading to bloating, but they believe it has to do with the amphibians’ physiology. Wood frogs can survive cold temperatures during the winter, by moving water into extracellular areas in their body, where it can be stored safely without damaging the rest of the cell. At the same time, they concentrate sugar in their cells to stop them from freezing. The species can tolerate the freezing of about 65-70% of the water in their body in the winter. This technique keeps them alive through spring in the northern parts of their range.

Usually, after thawing in the spring, wood frogs will lose the water they stored in these extracellular spaces. But it’s possible that road salt is affecting the frogs’ ability to quickly shed this extra water.

Two frogs from a roadside pond in a mating position. Credit: Steven Brady

In the meantime, he worries that the bloating might slow frogs down, making escape from predators more difficult. This slowness could also mean they spend more time on the roads while crossing, opening up more opportunities for vehicle collisions.

What’s more, during the spring when the roadside frogs emerge bloated, it’s also mating season for the species. Bloated males may be at a disadvantage when reproducing, as mating requires them to latch onto a female without being dislodged by competitors. “Usually, the male will wrap its arms around the female and hang on for dear life,” Brady said.

Bloating is not the only issue that salt is causing for wood frogs. Brady and his colleagues’ past and ongoing studies have shown a number of other effects in frog populations along roadsides, including malformations in the larval stages and lower survival.

“In a lot of ways, those roadside populations end up maladapted compared to those farther away from the road,” Brady said.

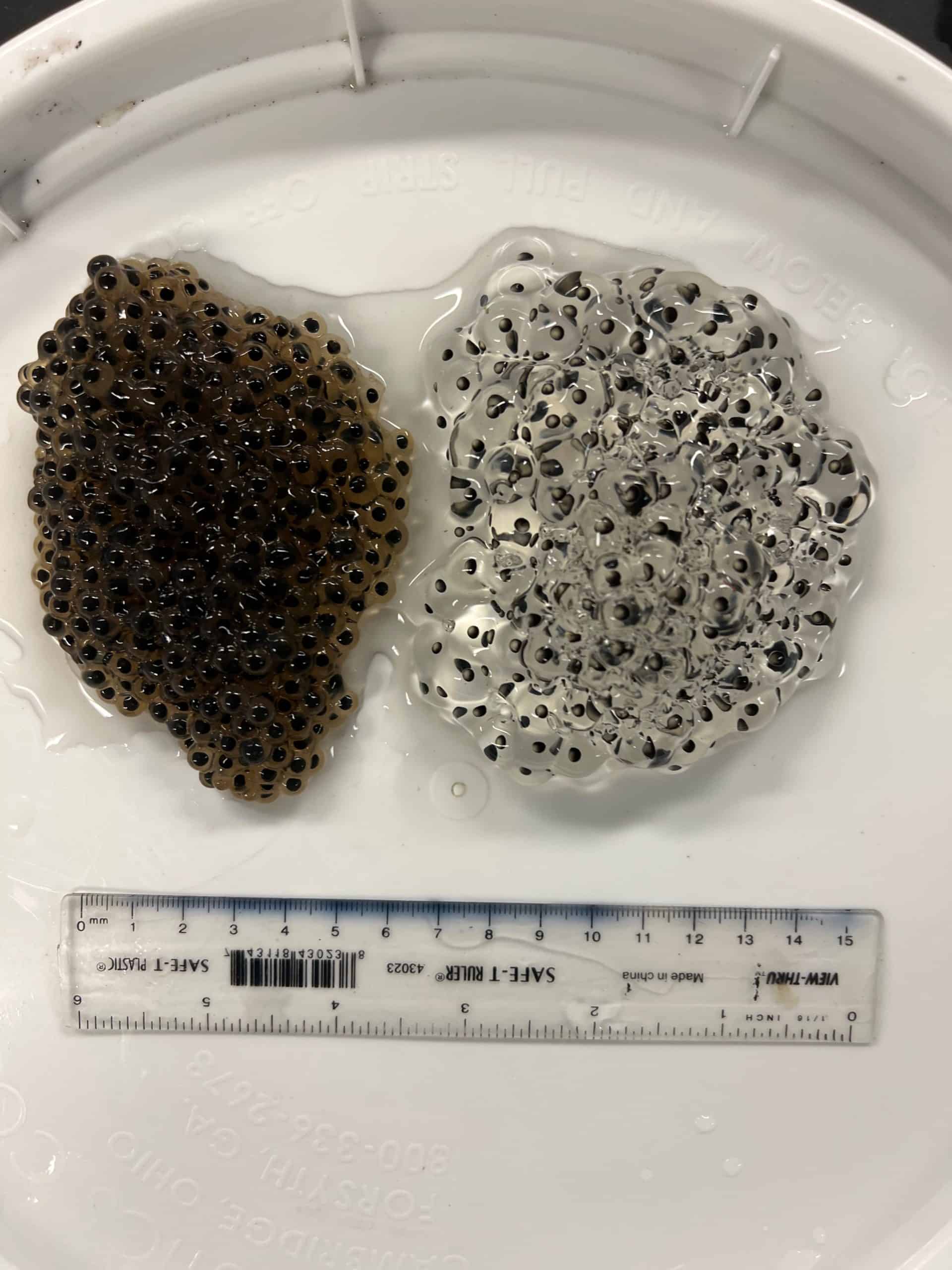

The eggs on the left were taken from a polluted roadside pond, while the ones on the right were from a clean pond. The roadside eggs are more numerous, but have darker jelly due to pollution. Credit: Steven Brady

At the same time, his research shows it’s possible that some frogs near roads are actually adapting to saltier conditions—one of his studies shows females close to roads jump farther than those that live away from roads. The females close to roads also lay more eggs.

Researcher Steven Brady holds a bloated frog. Credit: Daniel Bolnick

Altogether, the evidence shows that even smaller quantities of road salt currently seen as below the dangerous threshold by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency can have negative impacts on amphibian populations.

In addition, even if we stopped using salt tomorrow, Brady said it would take decades or longer to work its way out of aquatic ecosystems. “We have a big problem on our hands with salt,” he said.

Header Image: A bloated wood frog found near a road in New England. Credit: Steven Brady