Share this article

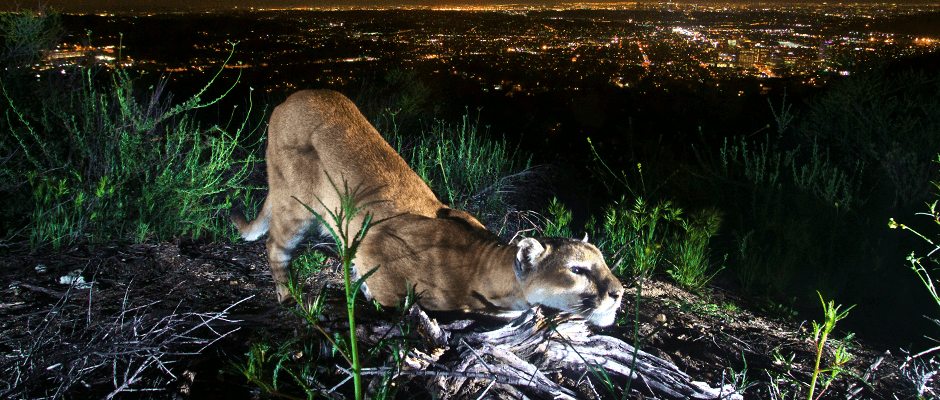

Mountain lions face inbreeding threat in Santa Monica Mountains

A small population of mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains might be facing inbreeding problems and potential extinction in the next 50 years, according to new research.

In Los Angeles, the second largest metropolitan area in the country, there are problems of urbanization and fragmentation for wildlife, especially species such as mountain lions that need a lot of space, says TWS member Seth Riley, who is a wildlife ecologist with the National Park Service at Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area and a senior author in the recent study. The area’s mountain lion population is especially fragmented due to Highway 101, a nearby eight-lane freeway — putting the population’s genetic diversity at risk.

“It’s an amazing thing to have a large carnivore left in Los Angeles, and it’s a testament to open space being preserved,” Riley said. “But not surprisingly, there are serious challenges.”

As part of the study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B., the researchers conducted a population viability analysis of the mountain lion population in the Santa Monica Mountains where they looked at population demographics including survival and reproductive rates of the animals to determine how likely the population is to go extinct. Further, because the researchers had genetic data collected on the individual’s that were studied throughout the years, the team was also able to model different scenarios of genetic diversity for the mountain lion population.

The initial result of the population viability analysis showed that population is reasonably stable, with good rates of reproduction and adult survival, according to Riley. He says this means the habitat in the Santa Monica Mountains is good for the species, there is enough deer for them to eat and they are staying out of people’s way. But the model still suggested that there’s a 20 percent chance of extinction for this population in the next 50 years due to the small size of the population and habitat fragmentation. “Our job working with the Park Service is to make sure this doesn’t happen,” he said. “Just based on demography, it’s already a concern.”

The team then looked at how genetics and inbreeding would play into this. They found that genetic diversity would continue to decline steeply, and that once inbreeding depression begins to affect vital rates, there is a 100 percent chance of extinction in 50 years if nothing is done to connect the species’ habitat. Riley says increasing migration of mountain lions into the Santa Monica Mountains would lessen their chances of extinction. In fact, if migration levels increase even to just one every two years, the 20 percent chance of extinction based on demography will drop to 2 and a half percent, and genetic diversity is maintained, he says.

One way to remedy the situation is to create a wildlife crossing over the freeway, Riley says. There have been crossings around the world, but no one has ever put up a crossing over a freeway this big, he says. “It’s a unique and exciting project but it’s also an expensive one,” he said, adding that it would likely cost about $50 million.

According to Riley, increasing movement is critical. “But it’s not like you need a parade of mountain lions. Just one every couple of years is enough to make a big difference.”

Header Image: ©National Park Service