Share this article

Migrating birds choose native fruits over invasive berries

Migrating birds passing through New England go out of their way to find native berries to fuel up on for their southward journey, despite a plethora of invasive fruits available.

New research shows that despite growing numbers of late-season invasives, they may not serve as a good substitute for native fruit as climate change prompts birds to migrate south later in the fall.

“Birds are discerning, and they prefer native berries to invasive fruits,” said Amanda Gallinat, a postdoctoral researcher in biology at Utah State University and the lead author of a study published recently in Biological Conservation.

Gallinat was part of a team looking at how climate change was affecting bird migration timing while conducting her doctoral research at Boston University. Records from a long-term bird banding site in Manomet, Mass., near Plymouth, indicated that native species like hermit thrushes (Catharus guttatus) and Baltimore orioles (Icterus galbula) were migrating through the area later in the fall as temperatures warmed.

A gray catbird eats native pokeweed berries. Credit: Ann Stinely

She wondered whether the availability of the fruits that some migratory birds rely on was impacted by climate change, so she started to look more closely at when berries were ripening.

Gallinat and her colleagues Richard Primack at Boston University and Trevor Lloyd-Evans sampled the types of fruits available around the trails and mist nets that bird banders used at the Manomet site. They also collected fecal samples that the birds left during the mist netting process and analyzed them for fruit seeds.

During the late autumn when banding was taking place, they found invasive berries like Asian bittersweet, Japanese barberry and multiflora rose more often than native fruits like blueberries, black cherries and raspberries on the landscape.

Based on more than 450 fecal samples, native frugivorous or omnivorous birds consumed a small number of invasive berries — particularly bittersweet ones — but generally, they didn’t prefer invasive fruits.

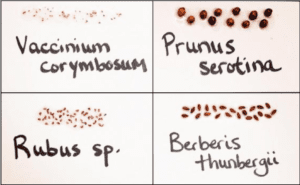

Researchers used a reference collection of seeds from plants in the field at a bird banding station at Manomet, Mass., to identify seeds. Clockwise from top left: native blueberry, black cherry, raspberry and invasive Japanese barberry. Credit: Amanda Gallinat

“Even though [invasive berries] were much more abundant in the environment in the late autumn, the birds were preferentially consuming native fruits during that time,” Gallinat said, adding that previous research showed that many of the invasive berries had lower nutritional value than the natives.

“These migratory birds need to store up for what can be incredibly long autumn journeys, so they can’t afford to eat nutrient-poor fruits,” Gallinat said.

Research elsewhere has shown that some native birds do make use of invasive plants, Gallinat said, but because migratory birds need fat to make their long-distance trips, they may find a diet of nonnatives has a greater impact on fitness and mortality.

Since climate change may be affecting the timing of migrations in relation to fruit blooms, she said, it’s important for land managers to make sure enough late-season fruits are available on the landscape for birds — they shouldn’t assume that invasive berries can fill those gaps.

“Climate change and invasive species are really combining to change what possibilities exist for bird-fruit dynamics,” she said. But maintaining native fruit availability will continue to be important in allowing for flexibility in migrations.

Header Image: Birds like this hermit thrush will increasingly encounter invasive fruits like multiflora rose as they migrate later due to climate change. Credit: Jeremiah Trimble