Share this article

JWM: Crows contribute to Karoo dwarf tortoise decline

Human-created structures like windmills and telephone poles are giving crows and ravens a place to nest, enabling them to colonize treeless areas where they prey on young, endangered Karoo dwarf tortoises in South Africa.

Those predations are likely driving the population numbers down.

Karoo dwarf tortoises (Chersobius boulengeri) are one of five species dwarf tortoise species found in southern Africa. Four of those are endemic to South Africa, while the fifth is found in a small region across the border in Namibia. The Karoo species is found only in a small part of the Karoo—a mostly arid region in the south central part of the country—and researchers only know of one wild population that remains.

The species is considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature mainly due to habitat loss. But researchers don’t really know how the population is doing, let alone its specific habitat needs.

“No one ever looked at their ecologies,” said Victor Loehr, an ecologist with Dwarf Tortoise Conservation, a nonprofit volunteer organization focused on improving knowledge and conservation of these African reptiles.

A tortoise fitted with a radio transmitter tracking device. Credit: Victor Loehr

Loehr and his colleague Toby Keswick, also with Dwarf Tortoise Conservation, set out from 2018 to 2020 to survey Karoo dwarf tortoises and learn more about them. They published a study on their findings recently in the Journal of Wildlife Management.

Finding the tortoises to attach tracking devices proved difficult. “We knew in advance that Karoo dwarf tortoises are very difficult to find—there are very few records of them,” Loehr said. But they didn’t realize just how difficult it would be.

When the researchers discovered individuals, they removed them—adults measuring only about 10 centimeters from head to tail—from the small crevices or cracks in the rocky substrata, gathering as much data as they could about individuals and fitting some with radio transmitters.

The tracking data revealed part of the difficulty in finding them was because the tortoises spend little time out in the open. Most tortoises are active in the morning and late afternoon, but the Karoo tortoises only came out during the latter period, emerging to feed on plants for about five minutes per day, on average. Otherwise, the tortoises mostly stayed hidden.

“They are able to use the energy they get very efficiently, even for tortoises,” Loehr said.

Field personnel record measurements of dwarf tortoises in the field. Credit: Victor Loehr

Temperature measurements showed that by shifting their postures slightly, the animals managed to maintain optimal temperatures.

The researchers only found 3.3 tortoises per hectare. That’s low compared to the closely related speckled dwarf tortoise (Chersobius signatus)—the world’s smallest tortoise found in densities of about 15-20 individuals per hectare. Loehr said the low density of Karoo tortoises is strange because the region where they are found produces more plants that the tortoises eat than the regions where speckled dwarf tortoises occur.

Loehr and Keswick also found a serious problem with the population make up. Most of the tortoises were old—few juveniles and hatchlings turned up in their surveys. “That population should have juveniles that increase in size and enter the adult part of the population,” Loehr said.

They x-rayed females and found that they developed eggs. The team even found some of the three-centimeter newborn tortoises next to eggshells, so they knew they were hatching.

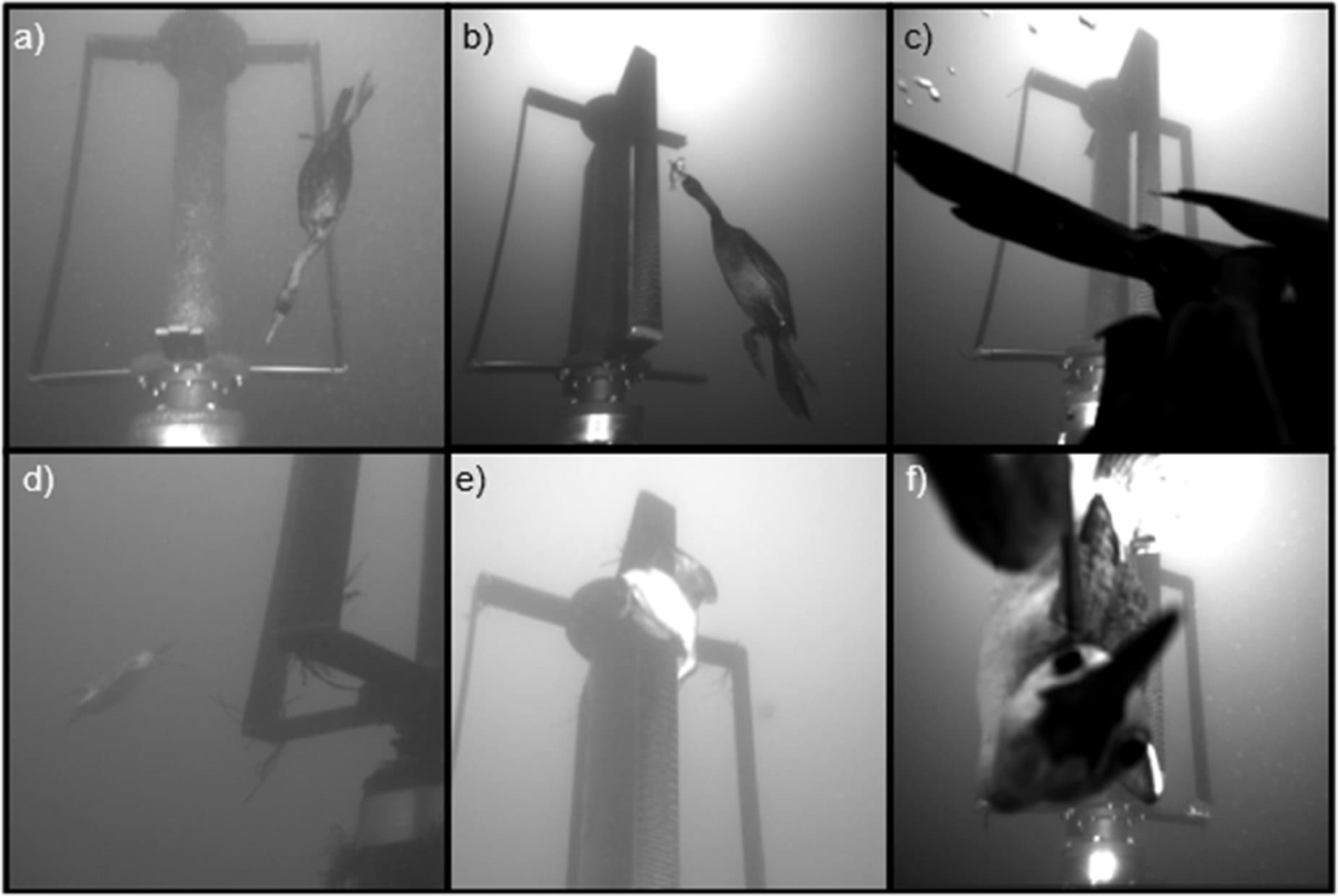

The researchers suspect the lack of juveniles in the population is due to pied crows (Corvus albus) and white-necked ravens (Corvus albicollis) in the area persistently preying on them. The researchers didn’t witness this predation directly, but they found Karoo tortoises smashed open—corvids are known to drop tortoises on rocks to crack open their shells for easier feeding. “Every day, we saw ravens patrolling for prey,” Loehr said.

The ravens and crows are native to South Africa, but crows, especially, aren’t usually found in these parts of the Karoo. The Karoo dwarf tortoise population was about 60-70 kilometers from the nearest town—“it’s really in the middle of nowhere,” Loehr said. There are low levels of sheep herding, but the sheep themselves don’t seem to be a problem—the area is almost like a nature reserve.

“We had imagined that a tortoise population that lived that far from people would be safe,” he said.

But farmers erect artificial basins to provide water for their flocks—water that could also be sustaining the crows and ravens in an area they wouldn’t normally be able to access.

Furthermore, many windmills have been constructed to pump the water, while telephone poles also run through the area. These structures act like “artificial trees,” Loehr said, giving the corvids places to nest and perch while they survey the land for prey.

Crows and ravens are probably dropping tortoises on rocks to crack open their shells for easier feeding.

Credit: Victor Loehr

There are a few remote roads in the area, but even these sometimes produce roadkill that likely subsidize the birds as well.

The roadkill problem would be difficult to solve, Loehr said, since people drive fast in these remote areas. But some of the other problems would be easier to fix. Nobody in the area uses wall telephones anymore with the advent of cellphones. The telephone poles could just be removed. Meanwhile, the water troughs could be made crow-proof.

Predation may have also led to the disappearance of other populations of Karoo dwarf tortoises, Loehr said. Overgrazing in areas where the reptiles were previously found may have led to habitat degradation, especially during drought, isolating some populations that then blinked out due to predation.

Researchers record the body temperature of a hatchling Karoo dwarf tortoise. Credit: Victor Loehr

“Analysis showed that 90% of the range of Karoo dwarf tortoises is degraded. That’s probably why the species is not doing so well,” Loehr said.

To deal with this situation, Loehr said, the government would need to take action, working with farmers to decrease overgrazing and maintain a better-quality native ecosystem.

“There isn’t necessarily a clash between Karoo dwarf tortoises and sheep farming, if you do it sustainably,” Loehr said.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: Adult Karoo dwarf tortoises only measure about 10 centimeters from head to tail. Credit: Victor Loehr