Share this article

Hundreds of land snails have gone extinct in the past century

Most people don’t pay much attention to snails — especially when the pea-sized gastropods live on a rocky uninhabited islet in Hawaii and don’t even have a name.

But Norine Yeung, the curator at Bishop Museum in Honolulu, and a small cadre of fellow malacologists, are passionate about the critters. They’re seeking to survey, and in some cases protect, the dozens of imperiled land snails that are endemic to the archipelago.

Enlarge

Credit: Norine Yeung

“It’s definitely hard finding them, but it’s like a treasure hunt sometimes,” said Yeung, who tries to make her study subject exciting to others by using Star Wars-themed backgrounds (like the one above) in the snail photos she uses in PowerPoint presentations.

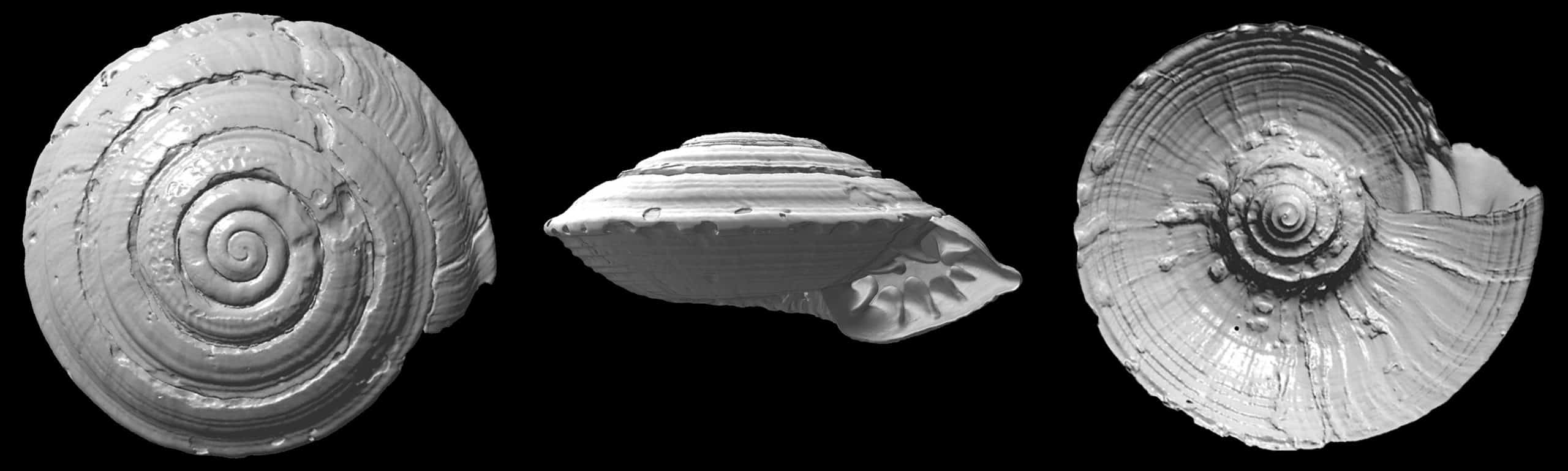

Yeung and her colleagues’ most recent hidden treasure was Endodonta christenseni. The tiny snail — the only living member of its genus — was gathered along with other specimens found on the small, uninhabited island of Nihoa, an isolated rock jutting out from the sea about 200 miles northwest of the Hawaiian island of Kauai.

During what is known as the Tanager Expedition in 1923, biologists conducted a series of surveys for a number of species on the island in which they reported the Endodonta christenseni. But that particular snail wasn’t seen again for decades. In fact, it was with the publication of a recent study in Bishop Museum Occasional Papers by Yeung and her co-authors that Endodonta christenseni was even given its name.

Enlarge

Credit: David Sischo

Over the near-century between its discovery on Nihoa, pictured above, and its naming, Endodonta christenseni has become emblematic of the types of problems all Hawaiian land snails face. Based on old museum specimens, there used to be at least 750 species of snails on the island, Yeung said. But many of these specimens were gathered in the early 20th century or earlier. Surveys she and her colleagues have conducted in the past few decades have revealed only about 300 species remaining. The rest have likely succumbed to a number of problems affecting Hawaiian wildlife in general, from habitat destruction to invasive species.

“It’s a sign that something’s happening in the ecosystem that we should be paying attention to,” Yeung said.

Hawaii doesn’t have any native ant species, but a bevy of invasive ants prey directly on snails, as do invasive rodents, mongoose, invasive chameleons and other species. Meanwhile, invasive plants also outcompete the native plants that land snails rely on for survival — while Hawaiian land snails don’t eat live plants or seedlings, they decompose their fallen leaves and scrape biofilm off the plants.

Part of the problem with these gastropods is their infamous slow pace. If their habitats are destroyed by cattle or the encroachment of invasive plants, it’s not easy for snails, sometimes as small as a grain of rice, to pick up and find a new area to live.

“Snails don’t move around readily,” Yeung said.

Enlarge

Credit: David Sischo

Snails play a critical role in the Hawaiian ecosystem that isn’t fully understood or appreciated, Yeung said. They eat fungi, possibly spreading spores in the process, and recycle detritus and leaf litter. “As my third-graders put it, they poop out fertilizer packets,” said Yeung, who sometimes does outreach with students.

They provide a food source for native Hawaiian birds such as the poʻo-uli (Melamprosops phaeosoma), and even for “a cool endemic caterpillar that eats snails,” she said, referring to Hyposmocoma molluscivora.

Endodonta christenseni is one of only two known live species left in the Endodontidae family.

“It’s an irreversible loss of a unique lineage that had millions of years to evolve,” she said, adding that they are also important culturally for Hawaiians. “It’s part of our story of growing up on these islands,” she said.

But Yeung likes to focus on what can be done to conserve the remaining 300 species of native land snails found in Hawaii. When she and her colleagues began to resurvey land snails in recent decades, they only knew for sure that about 75 species remained.

Enlarge

Credit: David Sischo

But there’s still hope for Endodonta christenseni. A campfire in 1885 wiped out a lot of vegetation on Nihoa, and Endodonta christenseni hasn’t recolonized much of that area. But Yeung and David Sischo rediscovered the snail in recent surveys, prompting the new study to give it a name — something many land snail species in Hawaii still lack due to the small number of people who study them.

“When we give it a name, we give it life,” she said, adding that at least 200 species of Hawaiian snails are still unnamed. “If you don’t have a name you can’t really put it on any endangered species list.”

Enlarge

Credit: Norine Yeung

Her team hopes to place the species into the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Snail Extinction Prevention Program or Bishop Museum captive rearing program, where they breed snails like the Amastra cylindrica pictured above in captivity to learn more about them and maintain backup populations in case numbers in the wild drop too low. Yeung said that a couple of the other species the two programs are breeding in captivity are extinct in the wild — the team is trying to increase the captive population inside predator-proof fences. One of the species is vulnerable since this species take nearly two months to emerge from their eggs after initial laying. Other species take several years to become reproductively mature, and produce only one offspring annually.

“If you don’t think it’s cute, it’s OK,” Yeung said after gushing over the slow-emerging species.

Enlarge

Credit: Norine Yeung

Sometimes people in the community will send in photos of snails thinking they are invasive, but they turn out to be a native species not seen in some time.

In one case, a survey of invasive snails on Mount Ka‘ala turned up a Kaala subrutila such as the one pictured above with baby, a species that hadn’t been seen since 1960 called. “Oh my god it’s still alive!” Yeung remembered exclaiming, adding that the species was named after the mountain on Oahu where it was found — many of the remaining species sit in high elevation refugia that haven’t seen the same level of habitat destruction. “We were ecstatic that it wasn’t an invasive species,” she said.

There are more than 60 invasive snail species on the island after the most recent count. Many of them were brought in nonnative plants — sometimes even on Christmas trees, Yeung said. Some snail species were purposefully introduced to control other invasive species, but those control species have since adopted a taste for native snails as well, pushing some to extinction.

It’s possible some of the others believed extinct are still out there as well. But there aren’t enough malacologists or community scientists interested in snails around in Hawaii. For now, many of the extinct species are only known based on what they left behind. It’s both a blessing that snails leave behind the shells that allow malacologists to identify their species, and a curse as they know how many have been lost.

“To go forward, we really need to have more people studying them and getting out there,” she said.

Enlarge

Credit: Norine Yeung

Header Image: Endodonta christenseni is only found on the small uninhabited island of Nihoa. Credit: David Sischo