Share this article

Gulf Spill May Have Affected Sea Turtles Across Atlantic

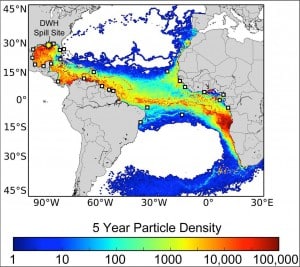

A new model combines ocean current information with sea turtle nesting data to find out which populations may have been the most affected by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

“The spill’s impacts were much wider than just that area where oil occurred,” said Nathan Putnam, a post-doctoral researcher in marine science at the University of Miami and the lead author of a new study published in Biology Letters.

He said that the information is critical for selecting mitigation strategies or in the awarding of restoration funds. “As far as restoration goes, if you want to restore injuries, to mitigate those losses, you need to know from which populations those losses occurred,” he said.

A report conducted for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in September 2015 contained estimations for the number of sea turtles that passed through oil spill areas based on the number of turtles rescue teams actually pulled out of the water in some areas. But the report didn’t look into where the turtles may have come from.

“Water surveys tell you that there are so many turtles in the water,” Putnam said. “You can’t tell what that means unless you know from which populations those withdrawals were made.”

Click image to enlarge. Yellow star Deepwater Horizon oil spill site distance from major sea turtle nesting sites (white squares). Colors indicate turtle density (counted daily). ©Nathan Putnam, Ph.D. UM Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science

Putnam’s study looked at three sea turtle species most affected by the spill: loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta), green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys kempii). They started with common predictions of the speed of ocean currents that moved through the area. They combined these with other data that predicted the number of turtles that hatched and survived into adulthood from 35 different Atlantic populations of the three species examined.

“Those models had been used in the past for fairly broad, general predictions about where turtles would be,” Putnam said.

The researchers found their initial numbers matched up very closely with the NOAA predictions for loggerheads and green sea turtles. The NOAA numbers predicted 30,000 loggerheads while Putnam and his team predicted 20,000-25,000. For green sea turtles, NOAA’s numbers were 150,000 compared to 175,000 in Putnam’s study.

But for Kemp’s ridley turtles, the numbers were initially very different, with Putnam’s data indicating only 3,000-4,000 compared to NOAA’s predictions of 212,000. This is due to a preference the Kemp’s ridlies display for going against the flow of the current and staying in the northern Gulf of Mexico area — normally good habitat for them if it wasn’t for the spill.

“The [Kemp’s ridley] turtles in that area tried to stay there. They swam in directions that would keep them in the northern Gulf,” Putnam said. “Taking into account the behavior of turtles is a useful thing to do in future modeling exercise.”

Where do they come from, where do they go?

All three turtles face problems. Around 75 percent of the turtles actually found dead around the spill were Kemp ridlies, considered endangered by NOAA throughout their range while the agency recently proposed distinct populations of green sea turtles in the North and South Atlantic for threatened listings. The agency considers some Atlantic populations of loggerheads threatened, and others endangered.

Putnam says that this is exactly why it’s important to know which populations of turtles were most affected by the spill, but current restoration assessments haven’t looked into the possible effects on turtles that come from international nesting sites, instead focusing only on U.S. nesting areas.

“Less than five percent of the turtles in that spill site arrived from U.S. nesting beaches,” Putnam said. “The most expedient way for restoration may differ whether it was Mexican turtles, Costa Rican turtles or U.S. turtles in the spill area.”

While NOAA has numbers on how many turtles were found dead around the spill area, the sublethal effects on turtle demographics aren’t very well understood. Putnam speculated that it could involve anything from impaired neurological functions in the turtles to changes in diet due to problems the oil may have caused to the blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) or other food they rely on. Or there may be little effect.

In any case, the model numbers he found in his study could be used again in the future to deduce other information. For example, researchers could use the number of known deaths into the model to predict which populations or nesting areas they may have come from.

“The same basic process we used here can pretty much be used in any situation.”

Header Image:

A heavily oiled Kemp’s ridley sea turtle recovered near the Deepwater Horizon oil spill site.

©NOAA