Share this article

Gone in an orange flash

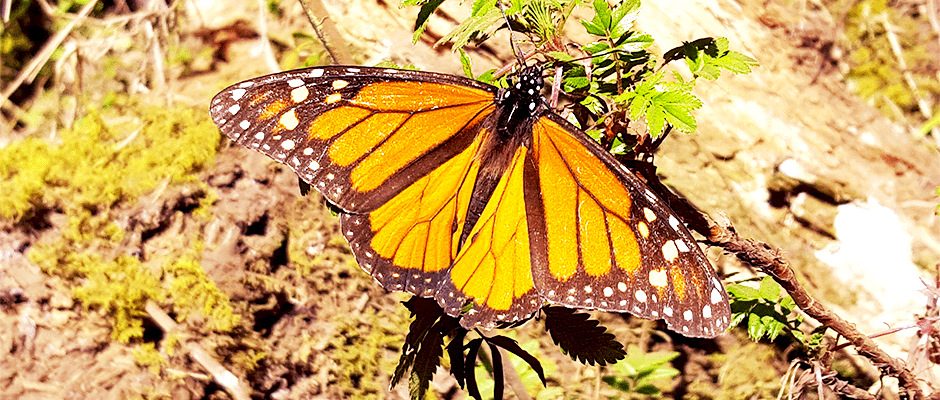

During migrations, eastern monarch butterflies used to swoosh by in an orange blur, but an 84 percent decline in over a decade has caused the colorful flashes to be a much rarer sighting.

In a new study published in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers found eastern monarch (Danaus plexippus) populations have a good chance of becoming quasi-extinct in the next two decades. “Quasi-extinction is when the population is so low it has no likelihood of recovery,” said Brice Semmens, an assistant professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and lead author of the study.

Semmens and his team looked at data from the last two decades on abundance of monarchs in overwintering forests in Mexico as well as total egg populations of eastern monarch butterflies. Estimations of population sizes were based on the geographic areas — measured in hectares — that the species covered while wintering in Mexico.

From this information, they built a population model in order to predict potential extinction risk in the future. “We were trying to determine at what point the population would go extinct and at what probability,” Semmens said, adding that they simulated when this would occur in 10- and 20-year time frames.

They found that there was about a 10 to 60 percent chance of quasi-extinction in the next two decades. For monarchs occupying a single tree in a forest in Mexico in the overwintering period, there would be a 10 percent chance of extinction.

As another part of the study, the researchers looked at what population targets would improve extinction risk. They found that by targeting 6 hectares of monarch coverage, there will be half the extinction risk over a long period of time. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is using this as a goal when planting milkweed in the butterfly’s breeding habitat, which suffers because of herbicides.

Environmental conditions also cause a large amount of variability year to year making it harder for them to recover from low numbers. “This is not something we can manage for,” Semmens said. “We can’t control when a winter storm hits Mexico, but we can control their habitat to increase their population.” Management goals for the larger population can decrease the species’ risk for extinction.

Despite a likelihood of quasi-extinction demonstrated in the study, Semmens still remains optimistic. “We’ve identified a considerable threat facing the population, and now we need to do something about it,” he said. “I’m pretty hopeful that true management action could recover the population to a point where it persists into the future.”

New Alaskan Butterfly Persists

While some butterfly species such as monarchs are fighting to survive, new butterfly species are becoming established.

The Tanana Arctic (Oeneis tanana) butterfly is the first new butterfly species documented in Alaska in the last 28 years, according to new research published in the Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera. Researchers suggest this species of butterfly might be the result of hybridization between two species — the Chrysxus Arctic (O. chryxus) and the White-veined Arctic (O. bore) — that are both adapted to the harsh arctic climate.

“Hybrid species demonstrate that animals evolved in a way that people haven’t really thought about much before, although the phenomenon is fairly well studied in plants,” said Andrew Warren, senior collections manager at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the University of Florida campus in a press release.

The butterfly has white specks on its underside and is larger and darker than the Chryxus Arctic butterfly. It also has a unique DNA sequence that’s close to the White-veined Arctics. “Once we sequence the genome, we’ll be able to say whether any special traits helped the butterfly survive in harsh environments,” Warren said. “This study is just the first of what will undoubtedly be many on this cool butterfly.”

Header Image: A male monarch butterfly rests at an overwintering site in the Piedra Herrada Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary in Mexico. ©Steve Hilburger