Share this article

Disappearing Arctic Ponds Could Affect Threatened Ducks

Ponds from north Alaska that provide “a mecca” for migratory birds and some threatened duck species are shrinking and disappearing, according to a new study.

“These birds will likely be affected because most of these birds feed on this system and in these ponds,” said Christian Andresen, a postdoctoral landscape ecology research at the University of Texas at El Paso and lead author on a study published recently in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences.

36 years later in August 2012, Christian Andresen, Ph.D., revisits the same pond once sampled by Butler, but it looks completely different; the pond has become overcome by plant growth.

Photo courtesy of Christian Andresen / UTEP

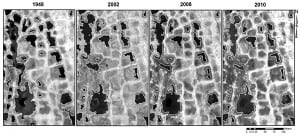

The study team analyzed satellite and historical photos from 1948 to 2010 to track long-term changes in more than 2,800 ponds on the Barrow Peninsula in Alaska. Researchers found that the number of ponds had shrunk by around 17 percent while the size of the small water bodies had diminished by around a third.

“This decrease in size and area and number is mainly due to warmer climate in this region, which contributes to permafrost thaw,” Andresen said, adding that the increased plant growth from the warmer temperatures could also result in water loss as the vegetation absorbs more liquid.

“[Vegetation} is encroaching these ponds. Over time this would lead to the disappearance of the ponds,” he said. “This has huge implications both on wildlife and on a global scale.”

For instance, disappearing or shrinking ponds could impact species like the steller’s eider (Polysticta stelleri) and the spectacled eider (Somateria fischeri), both of which are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. These species spend the winter in the Aleutian Islands in the south of Alaska then migrate to the north of the state and in parts of Siberia during the summer to nest and feed.

Satellite images show how Arctic ponds have slowly decreased in size since 1948.

Image courtesy of Christian Andresen / UTEP

The study also has implications for global climate change.

“The Arctic tundra is about 8-10 percent of the global terrestrial area,” Andresen said — and much of it is covered in these ponds. As they disappear and that surface area becomes covered in more vegetation, it could reflect the sun differently and affect climate change. The increasing amount of plants could also have implications for the carbon balance in the atmosphere, though Andresen said the study didn’t look at whether this would contribute to or mitigate a warmer climate.

Aside from analyzing images, Andresen also spent five of the past six summers in Alaska testing for thaw depth and water depths and comparing the results to test samples taken in the 1970s — what he referred to as “a life-changing experience.”

The team had to watch their backs for polar bears and carry shotguns to scare them away, though the closest call he had was coming within a few hundred yards of a bear.

“It’s a whole different world,” Andresen said.

Header Image:

Mac Butler, Ph.D., samples an arctic pond in northern Alaska in August 1976.

Photo courtesy of Christian Andresen / UTEP