Share this article

Conservation of the future

On more than one occasion, the Utah Community-Based Conservation Program has been touted as the embodiment of Aldo Leopold’s vision for wildlife conservation in North America. Ranchers Jay and Diane Tanner, long-time participants in the CBCP, have noted that the program has deepened and enriched stakeholders’ interest in and appreciation for the role of science in public and private land management.

It is no surprise, then, that the CBCP was recognized with The Wildlife Society’s 2016 Group Achievement Award — given each year to an organization exemplifying outstanding wildlife achievement consistent with, or assisting in advancement of, the objectives of TWS.

“I think the award recognizes the process and the people involved,” said Dr. Terry Messmer, Director of CBCP and the Jack H. Berryman Institute at Utah State University, and longtime TWS member. “The award really belongs to the communities. It’s validation of a process that if you get involved early on, you can shape the future of conservation.”

According to Messmer, the idea started when a group of landowners realized they had a problem — greater sage-grouse populations in the area were declining, and they weren’t sure why. That’s when, in 1996, Utah State University Extension and the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources began collaborating with communities to develop a community-based adaptive resource management working group process throughout the state. The goal was to enhance coordination and communication between local, regional and state governments, private stakeholders, and state and federal management agencies to reverse the decline of the ESA-candidate species.

It worked.

The CBCP has translated conservation planning into management, and management into population change. Local working groups, with their partners, have restored over 500,000 acres of sage-grouse habitat, protected 94 percent of the species’ population across 7.5 million acres, and effectively stabilized the species’ population throughout the CBCP area. Along the way, those affiliated with the program have engaged thousands of stakeholders through regular meeting, communications, two program websites, state and national forums, facts sheets, special reports, newsletters and even a mobile app.

“One of the biggest and most unsung contributions of the CBCP is the long list of graduate and undergraduate students who have been a part of the program,” Jay and Diane Tanner of Della Ranches wrote in a nomination letter for the Group Achievement Award. More than 80 peer-reviewed journal articles, dissertations and theses by more than 30 graduate students have come as a result of the program. “These students have developed a deeper appreciation of the role of private lands as part of the working landscapes which are essential for conservation. Thanks to them we have also developed a deeper appreciation of professional wildlife management. Many of these students are now employed in positions at state, federal, and academic institutions throughout North America. All continue to remain true to Aldo Leopold’s land ethics and the role of private land in wildlife conservation.”

Through the CBCP, local working groups — consisting of various stakeholders ranging from industry and private landowners to wildlife management agencies and environmental advocacy groups — share their perceptions, concerns and ideas, develop plans to identify key ecological aspects, and then pool their resources to conduct research that gives feedback on how to manage landscapes and the effectiveness of their efforts. The groups are defined by physiographic regions based on 11 known sage-grouse populations in Utah. In 2015, a plan signed into action by Utah’s governor that was built on the local working group’s efforts provided the science foundation for long-term sage-grouse conservation. Though the local working groups had been achieving success on their own for nearly two decades, the state-endorsed plan has provided the certainty to ensure long-term viability of sage-grouse populations.

Messmer believes the success of the program can be attributed to relationships built on trust. The selflessness and altruistic attitudes that these communities have shown toward conservation have brought them together in a common goal. He says they embraced the concept that if landscapes are managed for the whole, everyone’s interests and concerns will be protected by the process.

“I think this kind of process, this kind of engagement at the eye level, with local working groups and communities, is going to be the way conservation needs to be done in the future,” Messmer said. “I don’t think there’s going to be enough resources to buy, to lock up all the land areas that we need for conservation. For conservation to work, it’s going to have to engage all the partners to sustain working landscapes.”

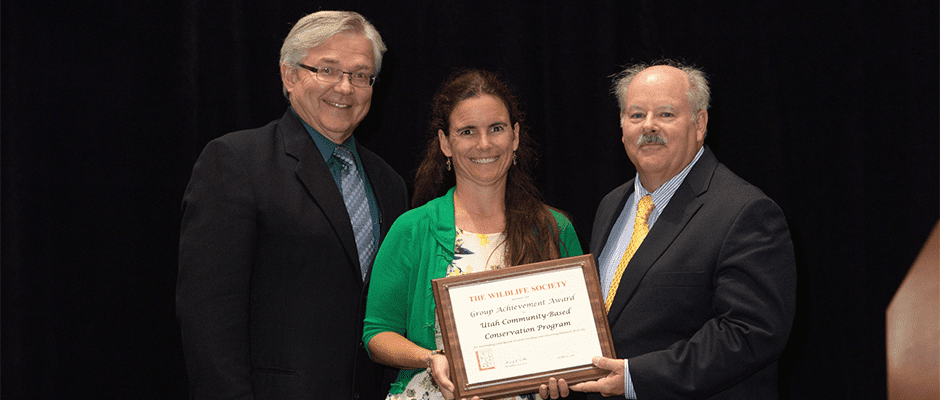

Header Image: Utah's CBCP Director Dr. Terry Messmer and Utah State University Extension colleague Nicky Frey accept the 2016 Group Achievement Award in Raleigh, North Carolina, on behalf of the program.