Share this article

Climate change is disrupting bumblebee communities

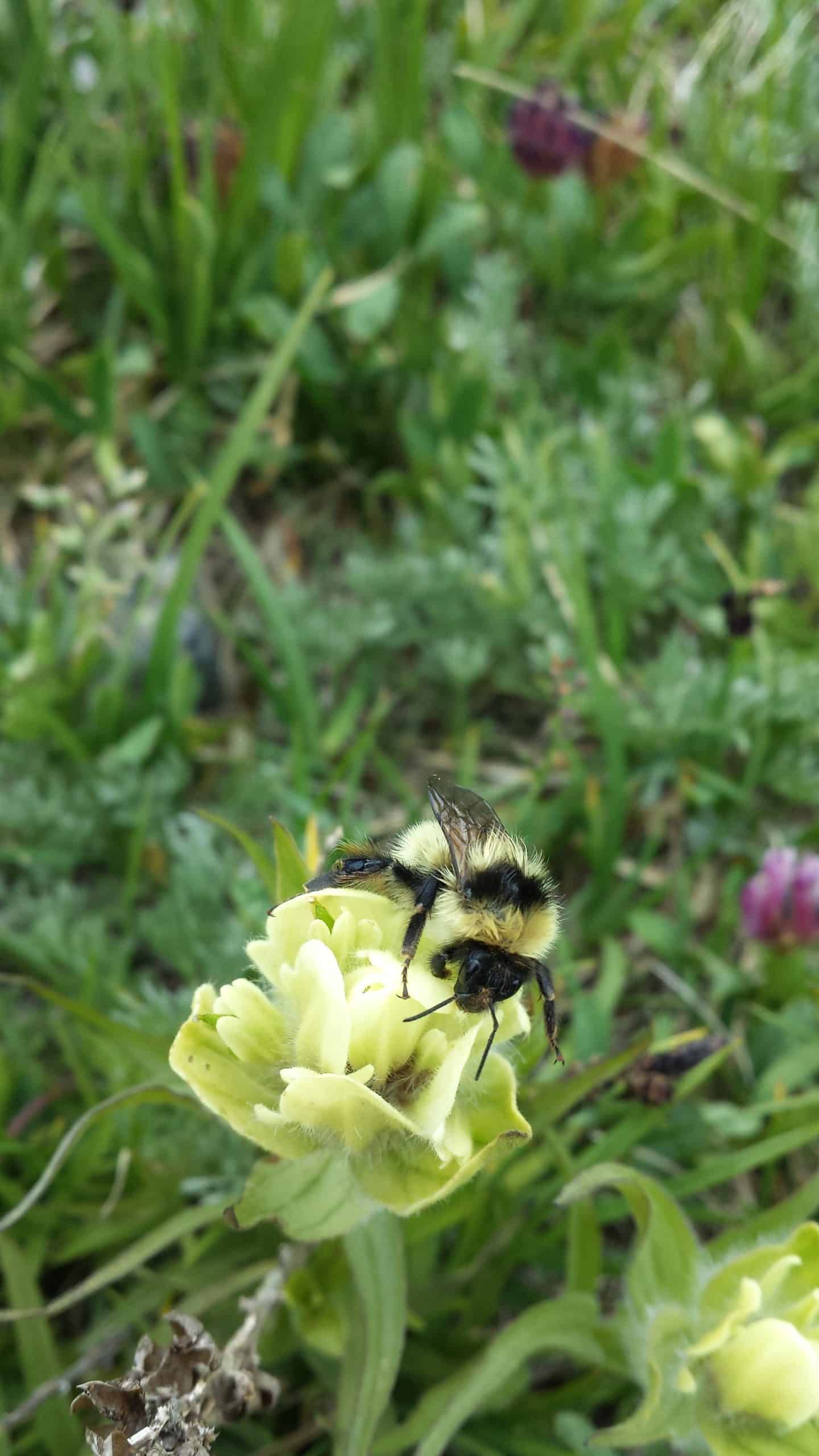

A warming climate is contributing to the decline of some alpine bumblebees and moving some subalpine populations to higher elevations.

Historically in the Rocky Mountains, two species of bumblebees stayed above timberline in high elevations, while a number of others remained at lower elevations. But as the climate has warmed over the years, researchers wondered how these important pollinators were responding.

“Bumblebees are probably familiar to most people. The fuzzy pandas of the bee world is how I think of them,” said Candace Galen, a professor emeritus at the University of Missouri. “And bumblebees, like many other kinds of insects, animals and plants are facing the effects of climate change. We often think of the animals and plants that live above timberline in the mountains, as well as in the far north in the Arctic, as canaries in the coal mine.”

Warming temperatures are creating a longer growing season at high elevations, causing the colder growing season the alpine bumblebees were once accustomed to, to be gone. Credit: University of Missouri

Galen and her colleagues wanted to find out how bees adapted to colder climates were responding to the changing climate. In a study published in Global Change Biology led by Webster University associate professor Nicole Miller-Struttmann, researchers tapped into historical data to compare the communities of bees at different elevations in the Colorado Rockies.

“In the Rocky Mountains where we worked, we were very lucky to have a long history of explorers and natural historians and scientists who have also been enamored by bumblebees,” said Galen, a co-author on the study. “There’s a lot of background information on where they were and how their populations were doing and what kind of flowers they were visiting.”

Her team set out to collect current data on the pollinators, with some help from high school students and their parents as well as college and graduate students. The researchers tried to collect the same type of information they already had from the same locations as before in order to remain consistent with the past data.

From late spring—before the snow melted—through August, they went out to alpine locations surveying for bumblebees and recording the timing and location of flowers they found. Then they compared their findings to those from the 1960s and ’70s.

Longer growing seasons and warming temperatures are allowing lower- elevation bumblebees to move upward into the alpine regions. Credit: University of Missouri

Instead of just the two bee species that historically nested above tree line, the researchers discovered eight different species. “The six newcomers were low-elevation bees historically, and now they’re among our most common species up high,” Galen said.

For her, the findings are both glass half-empty and glass half-full. “It’s glass half-empty in that for some alpine bees, they no longer have those areas all to themselves,” she said. “We don’t know exactly what the consequences of that will be.”

But the glass is also half-full, she said, because these subalpine bees were able to shift their ranges, possibly avoiding negative impacts brought on by warmer temperatures or habitat destruction. “They’ve been able to get up and get a foothold in refuge habitat up high,” she said.

The two historical alpine bee species were decreasing in abundance in the areas they studied, they found, likely due to climate change. “They can’t cope physiologically with these warmer temperatures,” she said.

Maintaining bee species is important, Galen said, because of their critical role in the ecosystem. “Their whole life history is interwoven in the natural world,” she said. High-altitude bees pollinate the wildflowers that pikas eat and nest in tunnels used by pocket gophers and voles. Elsewhere, bumblebees can serve as important pollinators for crops.

“If we lose the biodiversity of bees, then we’re beginning to tread on thin ice in a way because we’re losing backup forces for pollinating many of the crops we depend on,” she said.

Header Image: Researchers work in the high elevations of the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. Credit: University of Missouri