Share this article

Black Bear Reintroduction Shows Population Growth

In the first-ever comprehensive evaluation of the long-term success of a bear reintroduction technique called winter soft-release, researchers found that a reintroduced black bear (Ursus americanus) population in the Big South Fork area of Kentucky and Tennessee exhibited a high growth rate and that its genetic diversity has remained constant since the reintroduction occurred despite the population being demographically and genetically isolated.

In the study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, researchers used hair snares to sample bears that were first introduced to the area in 1996 and 1997. “There were no supplementations that occurred since the original 18 bears were released,” said Sean Murphy, a graduate student at the University of Kentucky and a Large Carnivore Biologist at the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries as well as lead author of the recent study. “They were pretty much left to be. Since 1998, there was no management and little research conducted until 2010 when we initiated our hair snare study.”

A black bear cub stands up against a tree in Big South Fork. In a recent study, researchers determined that the reintroduced population in Tennessee and Kentucky is increasing and has maintained its genetic diversity over time.

Image Credit: Sean Murphy

The bears were reintroduced using a technique developed by Joe Clark, a research scientist and branch chief with U.S. Geological Survey, and Rick Eastridge, a wildlife biologist with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Typically, when bears are translocated, they are moved during any season and hard-released without an acclimation period, Murphy said. In this winter soft-release method, researchers capture and remove females and their cubs from their natal dens during winter months and move them into either an artificial den or a natural one determined suitable for its size. “The general concept is that when the bears wake up, they are still in a den and acclimation occurs, improving the chances they stay in the release area,” Murphy said. “For them, they are still in the physiological phase of denning. The idea is that they’re more likely to stay there, especially since the bears are translocated as a family group because of the strong maternal relationship between mothers and their cubs.”

The reintroduced bears started with a small founding population of 18 bears in 1998 and grew to about 38 bears in Kentucky and 190 bears in Tennessee, suggesting that this method of reintroduction was successful at establishing a resident population. The average annual growth rate of the bear population was about 18 percent from 1998 to 2012, the researchers found.

“As a result, we believe this bear reintroduction technique can be effective at reestablishing bear populations,” Murphy said. “Although a small founder group was used, if bears are released in high quality habitat with protection from harvest and other mortality, relatively rapid population growth may occur.”

To conduct their research, Murphy and his team created a grid of the area surrounding and including where the bears were reintroduced in the Big South Fork River and National Recreation Area. They then established about 230 hair snares in this grid that were baited with pastries and sardines to attract the bears. Every week, the team re-baited and collected hair samples from barbed wire.

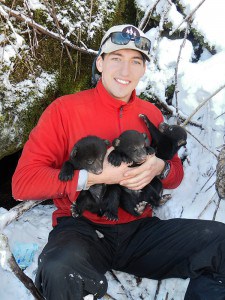

Lead author of the study Sean Murphy holds three black bear cubs. In a recent study, Murphy and his team used hair snares and collected data on the black bear population that was reintroduced in the late 1990s.

Image Credit: Tristan Curry

One of the researchers’ main findings was that genetic diversity remained relatively constant for the bears over time even though the population remained isolated. When comparing the genetic characteristics of bears sampled during 2010-2012 and bears sampled during 2000-2002, only two to four years after the reintroduction, Murphy and his team found that genetic diversity did not change all that much. They also found that the effective number of breeders, an alternate expression of effective population size, remained low but increased since the reintroduction. “You would normally expect diversity to decline because there’s little to no gene flow into the population,” Murphy said. When a population is under isolation, diversity can be lost at a rapid rate due to genetic drift, according to Murphy. However, there was no evidence of this occurring in this population. “We attributed that to initial high genetic diversity of the original founding 18 bears and the overlapping generations inherent to bears,” he said. “When you combine those things with rapid population growth, we think that allowed genetic diversity to be maintained despite isolation.”

Murphy recommends that continued monitoring should occur for this particular bear population since the population is still relatively small compared to other bear populations in the Appalachians and remains genetically and demographically isolated. But for now, he said, this research shows the potential success that can result when the winter soft-release method is used to establish a bear population from a small founder group.

“Few black bear reintroductions have occurred using this translocation method, but they were spearheaded by Dr. Joe Clark from USGS, who developed this technique and put it into action,” Murphy said. “Bear recovery and restoration in parts of the Southeastern United States may not have happened at the rate it has without his efforts and foresight.”

Header Image:

Four researchers hold black bear cubs. From left to right: Steve Bakaletz (Wildlife Biologist, National Park Service), Mike Ross (Forester, United States Forest Service), Joe Metzmeier (Wildlife Biologist, United States Forest Service), and Sean Murphy.

Image Credit: Stratton Hatfield