Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

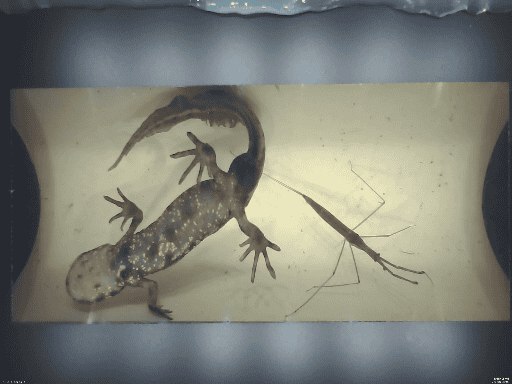

- Eurasian water stick insect

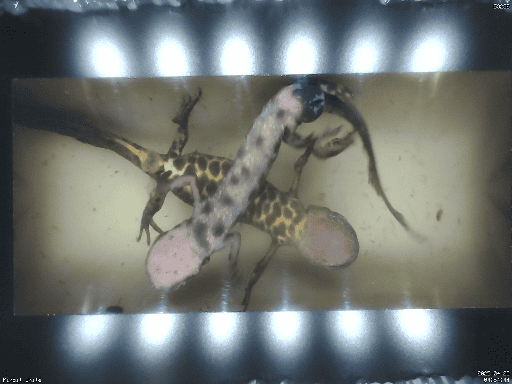

- Great crested newt

- Marbled newt

- Spotted salamander

Wild Cam: Underwater NewtCam identifies species using AI

New solar-powered device can help detect amphibians and other aquatic life without much disturbance

A new underwater camera is helping researchers automate species detection by taking candid shots of amphibians as they swim through an artificial tunnel.

The new technology can help researchers track the range of amphibian species and learn more about their habitat preferences in wetlands.

“Because it’s automated, you can survey more sites,” said Xavier Mestdagh, a biological engineer at the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST).

Researchers are now using this technology around the world to track and identify various aquatic creatures.

The great crested newt (Triturus cristatus) is protected in the European Union. To survey them, researchers at LIST were using a standard, older method of leaving live traps out overnight and counting captured amphibians in the morning. But this process took time and also likely stressed the animals, Mestdagh said.

In 2016, Mestdagh and his colleagues started to develop a new prototype system. The researchers set up the devices so that amphibians would enter a tube and motion detectors would prompt the camera into action.

Enlarge

After a few designs and years of testing, the team settled on a system with four funnel entrances leading to a single pipe in the middle. Newts would enter through one of a pair of funnels on one side and escape through a pair on the other side after their candid photo session. The bottom of the pipe was transparent in order to capture the photos—great crested newts have unique spot patterns on their bellies that allow individual identification. Follow-up image processing with artificial intelligence software in the lab then differentiated between the different species of newts found in the areas where it was tested in Luxembourg and at a site in southern France.

As detailed in a study published recently in Methods in Ecology and Evolution, the team demonstrated the ability of underwater cameras to produce observations of great crested newts at the larval stage when they already display well-contrasted belly patterns. Also, a controlled but still unpublished test revealed that larvae’s belly patterns are unique and stable a few weeks before metamorphosis. After metamorphosis, a newt’s patterns begin to become pronounced enough for individualization. At that point, each individual’s spots are more or less set for life. In the future, the team hopes to use the distinct spot patterns and device to estimate offspring production at the breeding sites.

Enlarge

In a blocked-off pond that the team used to test the device and standard live traps with a known number of newts, Mestdagh said both methods are producing observations of a similar number of individuals. “It’s a good indication that the NewtCam could be used for population estimates for the great crested newt,” he said. They also capture more photos of individuals at night than during the day, perhaps because amphibians were attracted by the light in the device. The newts may have also been attracted by the invertebrate prey attracted to the light, like the Eurasian water stick insect (Ranatra linearis) seen alongside the marbled newt (T. marmoratus) above.

Onshore solar panels power the device, so researchers can leave it out for a season with minimal maintenance visits. The buoyancy can also be shifted so that the entrance tubes either sit near the surface or rest on the bottom of the pond. Mestdagh said that the device can also be shifted onto its side so the camera takes shots from the side of animals swimming through rather than from the bottom. Depending on the species, this might improve identification of individuals.

Enlarge

Nicolas Titeux, a biologist and head of the biodiversity monitoring and assessment group at LIST and a coauthor of the recent study, said that the team is now using the NewtCam to determine how great crested newts are coping with extreme temperature at Pinail National Nature Reserve, which is the edge of their range near La Rochelle, an area close to Bordeaux in western France. He’s also interested in seeing how marbled newts, which are expanding northward, are interacting with crested newts where their distributions meet. The photo above features a crested newt female with a marbled newt male—the two species can produce hybrid offspring.

Enlarge

Mestdagh is also interested in using the technology for invertebrates, fish, reptiles and other aquatic wildlife. Early users have already validated the NewtCam in places as varied as the U.S., Brazil, Hong Kong and elsewhere in Europe. The gravid female spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) above was photographed in Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario alongside a larval dragonfly and other invertebrates.

These cameras have captured everything from still images of various aquatic species to video footage of species interactions. Researchers are seeing fights between crested newts as well as courtship displays or predation between species. These innovations point to the potential for more detailed studies on species interactions and behavior. Titeux also said that researchers could use the devices in some areas to track the species’ response to factors like drought.

In collaboration with the Natural History Book Service, the researchers are further developing the device and the related software to place on the market for use by other researchers, Titeux said. They are also looking for further international collaboration around the world.

Header Image: A marbled newt alongside two diving beetles captured in the NewtCam. Credit: Mathilde Foucteau