Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Clouded leopard

- Common leopard

- Red panda

- Yellow-throated marten

Wild Cam: Trail cameras reveal ‘elusive’ red pandas

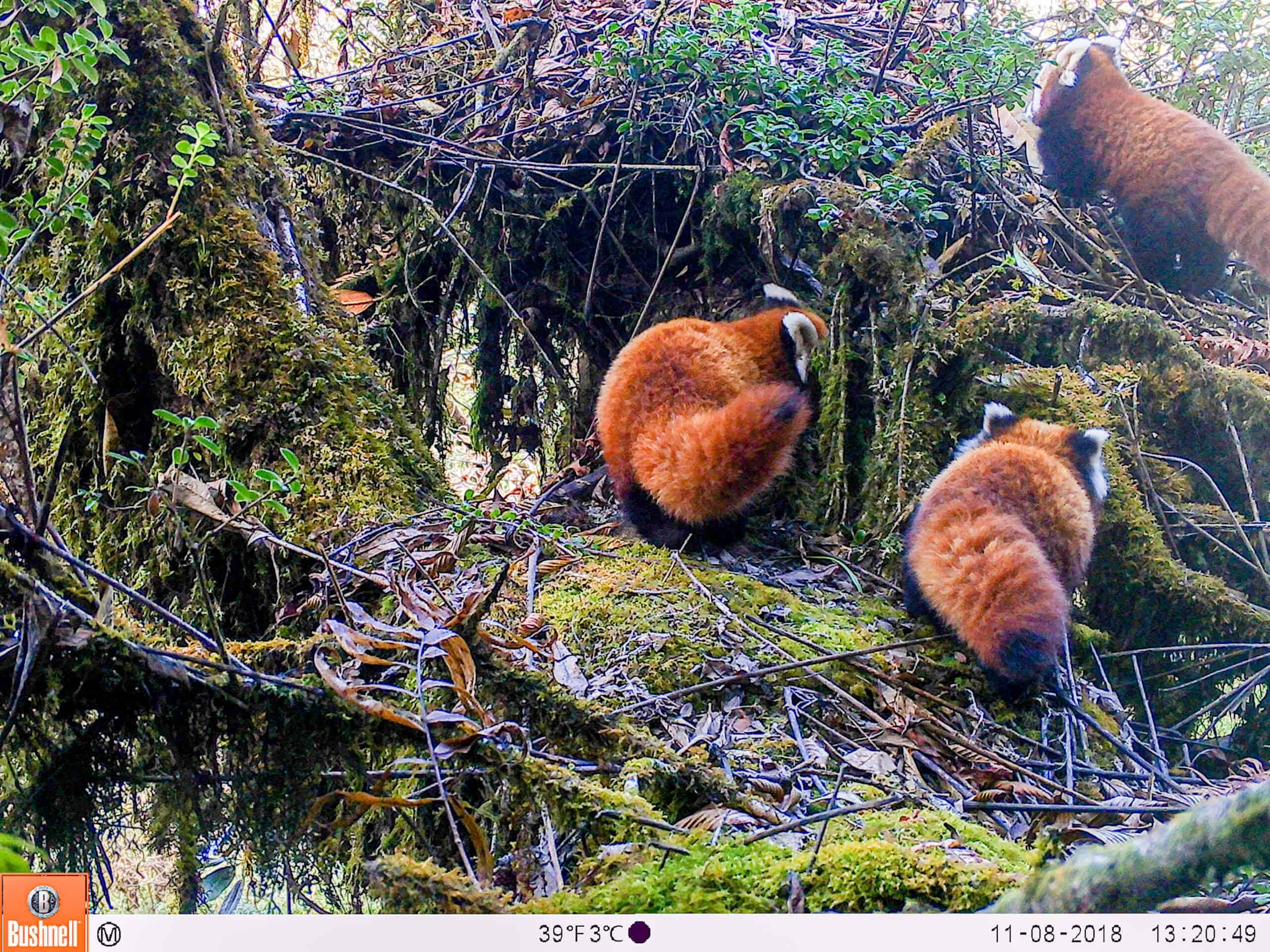

Researchers have taken camera traps to the tree canopies to find out more about endangered red panda ecology—where they prefer to live and, perhaps, what might kill and eat them.

“Red pandas are very elusive,” said Sonam Tashi Lama, conservation program manager with the Red Panda Network. That makes it difficult for researchers to learn about them from direct observation.

The forests of eastern Nepal used to be prime habitat for red pandas, considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. In recent decades, these forests have become fragmented due to a combination of increased grazing and tree harvesting for cooking and heating in the mountains. Poaching is also an issue—poachers target the animals for fur sales.

Enlarge

Credit: Sonam Tashi Lama/RPN/Lincoln University

The Red Panda Network is a nonprofit organization that uses a network of citizen scientists to educate locals and restore forest ecosystems in Nepal. But scientists involved with the network didn’t know how well trail cameras were going to work for monitoring this species whose red fur camouflages well with the moss often found on trees in the area.

In a study published recently in the Wildlife Society Bulletin, Lama, who conducted this work as part of his master’s thesis, and his colleagues tested the best way to place trail cameras to capture footage of red pandas.

In 2018, the team placed 19 pairs of cameras in the winter and again in the pre-monsoon season from March to May. They put the cameras in both the tree canopy and on the ground—red pandas are mostly arboreal but sometimes travel on the forest floor, often when accessing water.

Enlarge

Credit: RPN/Anish N. Vaidya

View from above

The arboreal cameras were eight times more effective than the ground cameras at capturing red panda footage, Lama said.

One of the challenges with getting cameras into the canopies is that it can be difficult to climb the branches, especially during the pre-monsoon season when branches can get slippery. But Lama said that Forest Guardians—citizen scientists who monitor red pandas from the area and get some funding from the Red Panda Network—are skilled tree climbers.

In addition, setting up these trail cameras is time-consuming, as citizen scientists often have to go back and change batteries and memory cards. Another problem is that in the tree canopy, things like leaves in the wind can prompt the motion sensor. These create false triggers for the camera traps that could mean extra lab work. Still, the tree cameras were effective.

The best places to record were basically bathroom cams. Red pandas will often return to the same latrine sites to defecate, usually on big oak trees next to the bamboo they feed on. They often live around these areas, as they can use the numerous sturdy branches of the oak to access bamboo.

Enlarge

Oak trees in this area are also often covered in a reddish moss that the pandas can blend well in. The camouflage is so effective that the researchers sometimes confuse pieces of moss with red pandas from afar. “It really helps to protect them from predators,” Lama said, adding that those predators likely include clouded leopards (Neofelis nebulosa), common leopards (Panthera pardus) and sometimes yellow-throated martens (Martes flavigula). The latter usually hunt in pairs and could easily take down a red panda, Lama said.

Enlarge

The data from the trail cameras revealed that in eastern Nepal, red pandas are active during both the day and the night. Lama said the animals are eating constantly, with only brief naps between gorging on bamboo.

Enlarge

The trail cameras didn’t capture any predation events, but they revealed that clouded leopards used some of the same trees as red pandas. In fact, a clouded leopard visited an area where a red panda mother was raising two cubs while the pandas were out foraging for the day.

Other work to learn more about the pandas is ongoing. Lama said that the Red Panda Network has fitted 10 of the creatures with GPS tracking collars, which has revealed that the animals almost exclusively stay in the larger, unfragmented sections of forest and rarely cross into neighboring India as a result of grazing and tree clearing around the border.

Enlarge

Meanwhile, the Red Panda Network continues to put up fences in some areas to keep out humans and livestock and support natural forest regeneration. Members of the network are also planting nurseries with endemic trees that red pandas prefer. They also go through red panda habitat four times a year, monitoring the animals and keeping an eye out for poaching or other illegal activity. The Guardians help to educate the local populations about red pandas and the need for reducing firewood gathering in prime forest ecosystems, Lama said.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: The Union for Conservation of Nature considers red pandas endangered. Credit: Sonam Tashi Lama/RPN/Lincoln University