Share this article

Does better habitat quality mean less disease for bees?

Past research has suggested that more pollinator biodiversity means less virus among bees. But researchers wondered if it was that simple and what mechanism may be behind it.

Was habitat quality driving patterns of bee biodiversity and having downstream effects on disease? Or could better habitat quality actually be making bees less susceptible to viruses?

In a study published in Ecology, researchers set out to measure two different pathways that could be affecting bee disease on winter squash farms in Michigan. One suggested a more direct effect of habitat on disease, also known as the habitat-disease relationship. The other suggested that habitat quality was influencing biodiversity, which then influenced disease, or the biodiversity-disease relationship.

“We were trying to see which pathway might be at play,” said Michelle Fearon, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan and lead author of the study. “Also, to be clear, both can be co-occurring, or happening at the same time.”

Fearon hoped to see what factors might help improve bee health. But she also hoped to shed light on an ecological theory known as the Dilution Effect—the hypothesis that diverse ecological communities limit infectious disease spread.

To conduct the study, Fearon and her colleagues looked at the surrounding environment at both local and landscape scales. On the local scale, they recorded floral density and richness (the number of flower species). On the landscape scale, they looked at the proportion of natural areas and the number of different landcover types surrounding the bee communities. Assessing the habitat quality, they tried to gauge the impacts on the richness and abundance of pollinator species.

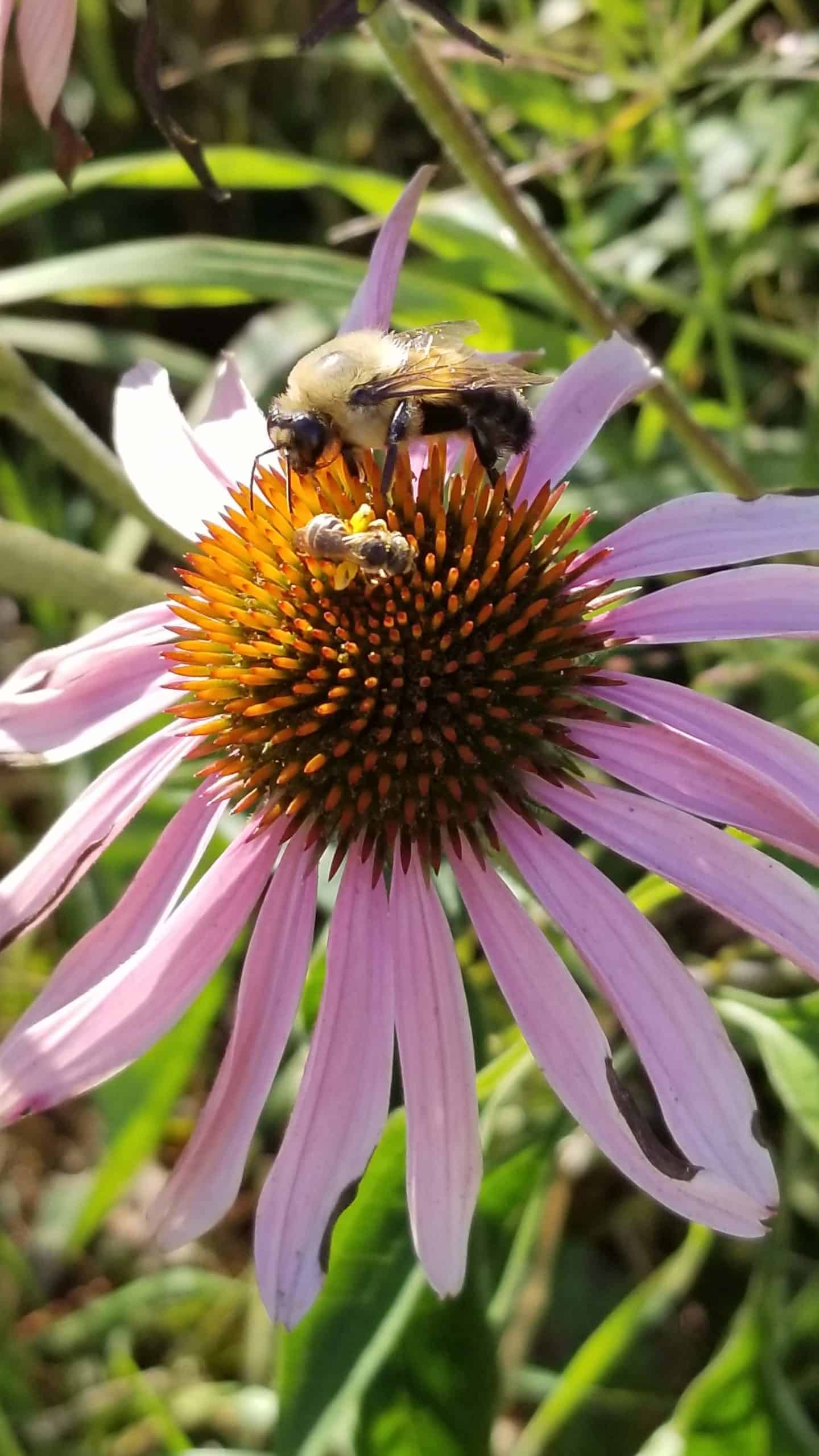

A male eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens) and a sweat bee on a coneflower.

Credit: Michelle Fearon/University of Michigan

They also looked at prevalence of three different bee viruses—black queen cell virus, deformed wing virus and sacbrood virus—and modeled for the two different pathways that could affect them.

Both pathways were occurring, Fearon said. Habitat quality was affecting pollinator diversity, which was then impacting virus prevalence. Consistent with the team’s prior work, greater pollinator biodiversity led to a reduction in viral prevalence. This showed that habitat quality could be driving the Dilution Effect by increasing pollinator diversity, Fearon said.

“But then it gets a little more complicated,” Fearon said of the evidence that habitat also had direct effects on virus prevalence.

The team found that greater habitat quality can have both positive and negative direct impacts on pathogen levels in bee populations, evidence for the habitat-disease relationship. “In this case, the direction of the result was dependent on the specific habitat quality metric and the virus we were looking at,” she said.

On the landscape scale, for example, more natural areas and land cover types may lead to more bee species and abundance. But they were also associated with increased viral prevalence. On the local scale, greater floral density was associated with reduced viral prevalence, likely because more pollen and nectar sources were available to help bees fight infection.

Overall, Fearon said, the study shows the importance of looking at how the different pathways work together.

“The combination of these two different pathways has the potential to either completely obscure the Dilution Effect in natural systems, making it hard to observe them, or compound on each other and make it appear stronger than they are in certain circumstances,” she said.

On a more practical level, she said, simply improving habitat quality may not be the answer to benefit bees’ health.

“We need to look at specific habitat quality factors we’re improving,” she said. “Just because high-quality habitat is likely to improve pollinator diversity doesn’t necessarily mean we’re also going to improve pollinator health as a whole.”

Header Image: University of Michigan researchers studied 14 winter squash farms across the state. European honeybees and wild native bees help pollinate the squash flowers. A diverse array of native bees occurred in the fields and along the field edges. Credit: Michelle Fearon/University of Michigan