Share this article

Turtles survive oil spills better after rehabilitation

When the Enbridge pipeline burst into a Michigan creek in 2010, Josh Otten was ready to help with the cleanup, especially since he knew wildlife was being affected.

“I was there day six after the oil spill occurred and quickly realized most of the wildlife that had been affected were turtles,” said Otten, who was working at an environmental consulting company at the time.

Spilling about 843,000 gallons of oil into a creek that drains into the Kalamazoo River, the accident put a particularly heavy burden on turtles, Otten realized. While affected birds could fly away from the contaminated waters, turtles didn’t have that option. When they left the water to bask, they became coated with oil.

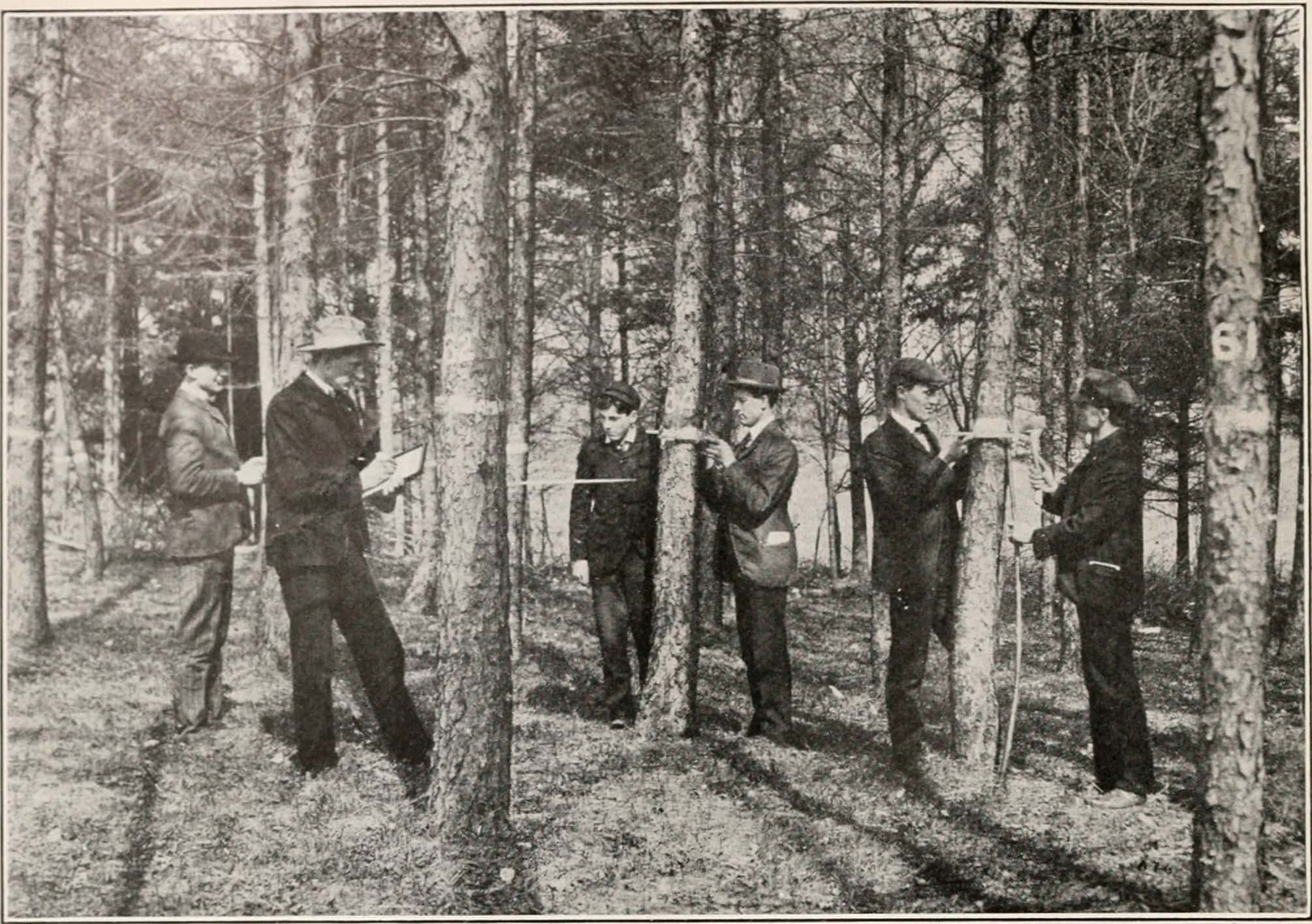

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other agencies set up a rehabilitation facility to clean up northern map turtles before returning them to the wild. Credit: USFWS

Biologists and volunteers spent months rescuing and rehabbing turtles, removing the oil with brushes and Q-tips. “In a rescue situation like that, it’s ‘Emergency! All hands on deck!’” Otten said. When they were ready to return northern map turtles (Graptemys geographica), the most common turtle species found in the Kalamazoo River, to the wild, they implanted some with PIT tags, collected measurements and released the turtles in areas free from oil, where they could eventually work their way back to where they were captured.

Fast forward about eight years. Otten’s advisor, Jeanine Refsnider at the University of Toledo, was looking for a PhD student to help her learn more about how these turtles had been faring after rehabilitation. Her team hoped that studying survival rates of turtles that had been individually marked in the aftermath of the 2010 oil spill would provide critical data on the long-term success of expensive and labor-intensive animal rehabilitation efforts, and could inform similar efforts following other oil spills in the future.

A biologist cleans a turtle after the 2010 oil spill in Michigan. Credit: USFWS

Otten had the experience she needed. He led a study published in Environmental Pollution trying to answer these questions. Otten and his colleagues looked at survival after three different rehabilitation treatment types. The first involved turtles caught in 2010 and 2011 with little or no oil on them that didn’t need rehabilitation. The second comprised individuals that went to the rehabilitation facility temporarily and were then released. The third included turtles that stayed in the facility over the winter, when they would typically go into a hibernation period.

They found that rehabilitated turtles fared better than the turtles that didn’t have any oil on them in the first place. “If they had gone through any type of rehabilitation, it increased their monthly survival,” he said. Turtles that had been kept over winter had the highest monthly survival. Otten suspects it may have something to do with them being well fed and avoiding any negative effects from the oil during hibernation.

The study suggests that rehabilitating turtles after an oil spill is worth the cost, Otten said, particularly since turtle populations can be impacted for years after disruptions in the environment. Because turtles are long lived and can take 14 years to reach sexual maturity, losing individuals can have devastating impacts to a population.

“If a population of turtles takes a hit like from an oil spill, a decrease in survival can cause detrimental impacts down the road,” Otten said. “Going through this process of rehabilitation was worthwhile for the population.”