Share this article

COVID-19 lockdown affects mammals across globe

As far as the average long-tailed macaque was concerned, life was pretty good in a small Thai village near the border of Laos. Tourists came through the village temple often, feeding the dozens of macaques that convalesced around the village temple and the nearby Phana Monkey Project facilities.

But then the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Tourism came to a halt in the area, leaving many of the primates scrambling for food. This kind of problem wasn’t unique—news reports in Bali, Indonesia reported that gangs of macaques, whose populations were artificially bolstered by food from tourists, were raiding people’s during the lockdown.

But in Phana, local villagers stepped in, averting potential wildlife conflict like what had been occurring in Bali. They fed long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) normally subsidized by tourists’ food.

“The monkeys were doing just fine—they were getting plenty of food,” said Lori Sheeran, an anthropology professor at Central Washington University who studies primates like these macaques.

While wildlife managers don’t usually approve of people feeding wildlife, the fact remains that many mammals on the planet depend on humans for food. Sometimes, we mean to feed them. Other times, we create conditions that favor creatures like coyotes (Canis latrans) or raccoons (Procyon lotor) by leaving out trash. Some species would probably benefit from people not being around—especially those people hunt or that are otherwise leery of our presence. But what happens when a global lockdown stops people from feeding, disturbing, hunting or otherwise interacting with many of these mammals?

Sheeran and her colleagues surveyed the scientific literature and news reports around the world to uncover the varied effects that the pandemic and related lockdown has had on mammals across the world. They published their findings recently in a study in Mammal Review.

The researchers, led by Rie Usui at Hiroshima University in Japan, identified 92 distinct animal reports representing 48 different species across the world included in the literature.

They classified each species into different categories, including ways that they were impacted by humans during the lockdown. They found that mammals that were attractions for humans before the pandemic, such as the macaque case in Thailand, were most frequently reported.

Mammals people used as a commodity were the second most commonly reported as impacted by the COVID-19 lockdowns. This included mostly situations where the animals were harvested or poached as bushmeat. Also in that category were mammals inside wildlife preserves that were supposed to be protected from poaching. The researchers found mixed results, Usui, said.

“Some wildlife populations face poaching risks while others don’t due to the halt in international travel and flights,” she said. But she added that for many populations, information isn’t yet clear on what has happened due to lockdowns.

The researchers found that in some wildlife preserves, concerns arose about the ability of caretakers, rangers or other related wildlife workers to maintain animals. For example, in some cases, they found that the lack of supporting staff at national parks in areas that depend on tourist dollars for funding may not have had the resources to police the parks for poachers.

For Sheeran, who studies primates, this could be particularly concerning for some species of gorillas with small remaining populations and limited conservation resources to protect them from poaching.

In other cases, the so-called anthro-pause that occurred with the pandemic lockdowns resulted in increased sightings of animals that were rare in some areas, such as around urban centers. With a lack of, or lower number of human activity, some mammals even changed the pattern of their activities, whether in space or time. Examples include wild boar (Sus scrofa), foxes, nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) and pumas (Puma concolor) roaming more conspicuously in cities.

Finally, Sheeran said that the researchers provided recommendations for future wildlife research moving forward, as well as policy regarding mammals. Since many primates can contract SARS-CoV-19 from humans, one recommendation for researchers working with those animals and other mammals is to continue to wear face masks and stay farther away when contact is unnecessary.

The researchers also recommend wildlife managers who deal with heavily poached mammals like elephants should have better financial support systems for times when tourism money doesn’t come in for one reason or another.

Finally, bushmeat markets need to be better regulated to stop the risk of zoonotic diseases jumping between species, like the recent coronavirus.

“Not only are [bushmeat markets] negatively affecting the numbers of wild animals, but they are also places where disease outbreaks are very common,” she said.

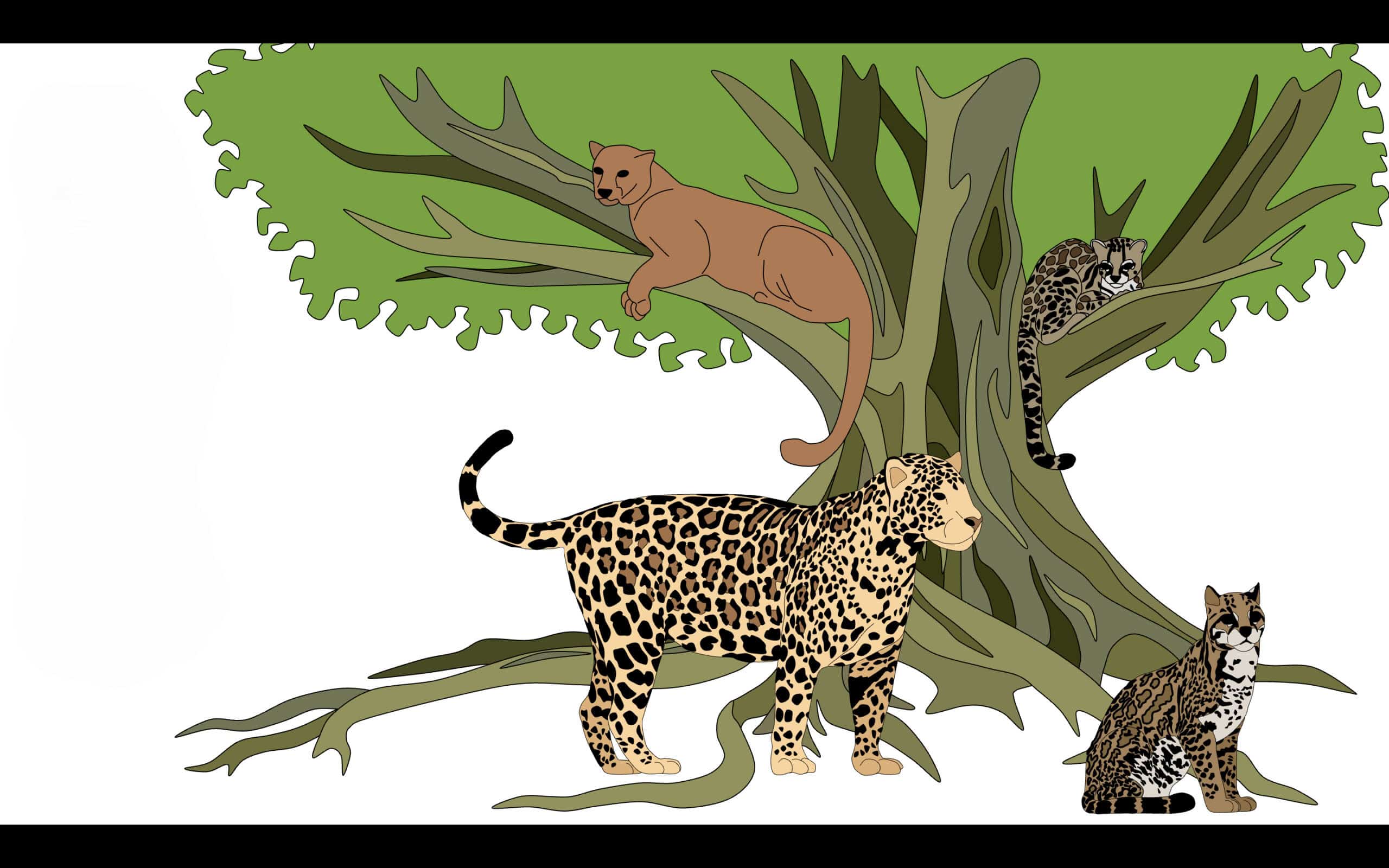

Header Image:

A long-tailed macaque from the Phana Monkey Project in Don Chao Poo Forest.

Credit: Ashton Asbury/Phana Monkey Project