Share this article

Salamander egg color reveals evolutionary forces at play

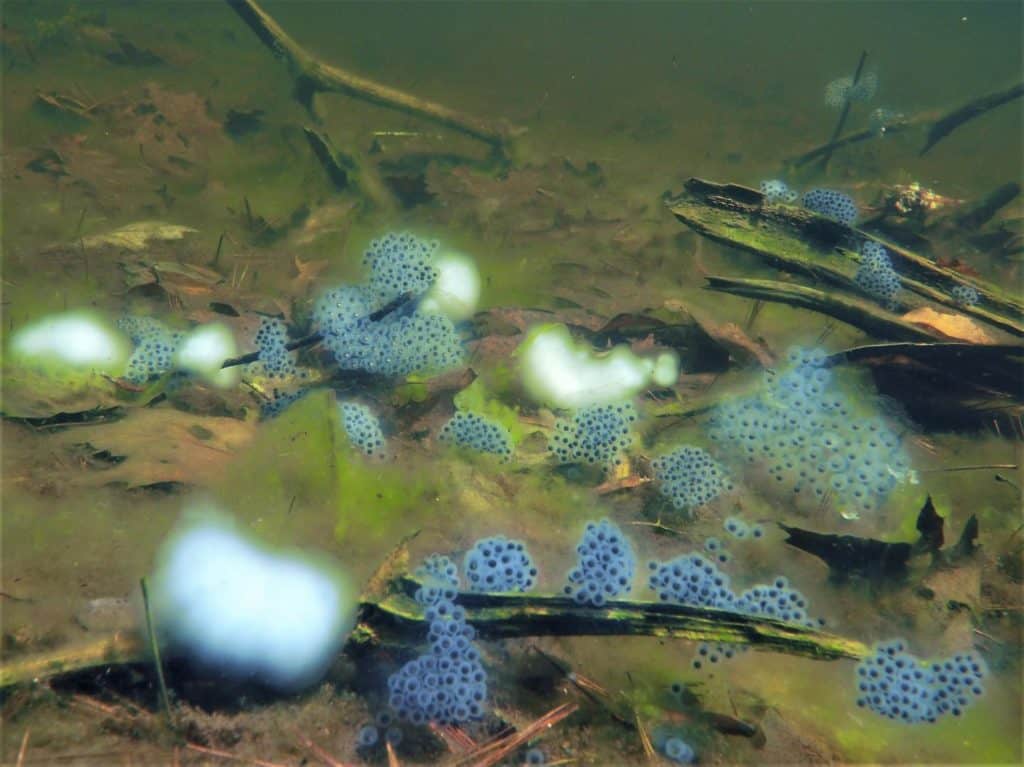

Poking through ponds in the northeastern U.S. when he was a child, Sean Giery remembers coming across different colors of spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) eggs — some that were clear and some that were white.

His curiosity about these different colorations came back to him while he was conducting other research on the salamanders as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Connecticut.

“It all started because I was working with these spotted salamanders for a previous postdoc, and one of the things we were doing was looking at inter-pond variation of traits,” said Giery, now an Eberly Research Fellow at Pennsylvania State University. “One of the things most obvious was the variation in frequency in white versus clear eggs from pond to pond, even on small spatial scales.”

Found across the eastern U.S., spotted salamanders return to ponds during the spring to reproduce. Egg mass colors are a heritable trait, and females lay the same color eggs throughout their lives. But researchers didn’t know much about the importance of these different colors and why the ratios of white-clear differ among ponds. Giery conducted some initial review of the literature and found that it could be that white masses were denser and better protect the developing salamander embryos against predators. Or it could be related to water chemistry. “Basically, something seemed to be going on, but it wasn’t really clear,” he said.

Luckily, data had been conducted on the egg masses in the ’90s, at a study site only about 5 miles from Giery’s house in Pennsylvania. “When COVID hit and I had some extra time, I resampled all of the ponds I could relocate,” he said. Comparing the contemporary and historical data from this metapopulation — a total of 31 individual populations — could help him determine if there had been any change in egg color ratios over the past 30 years.

In a study published in Biology Letters, Giery and his co-authors used these data to figure out if there were any changes in salamander egg color ratios and why those changes might have occurred. Using wetland maps from past dissertations and Google Earth, Giery tracked down 31 ponds and revisited them last spring.

The difference between white and clear eggs is pretty obvious, Giery said. “Once you have an eye for what you’re looking for, you can see them right away.” Giery went from pond to pond collecting information on egg masses and frequency of the two colors. He used polarized sunglasses to see them clearly, sometimes putting on waders and getting into the larger ponds to count the masses. The ponds are pretty clear, which helped, he said, since they are filled with either recent precipitation or snowmelt. He’d usually find the eggs on sticks or branches protruding from the bottom of the pond. He also collected some water chemistry data and information on pH of the pond, its conductivity and carbon content.

“It was an amazing way to spend the spring,” he said. “Spending a few weeks in early spring running around the woods and counting eggs, seeing new places, it’s just wonderful.”

After reviewing the data, Giery and his colleagues found that there hadn’t been a change in the overall frequency of white eggs since the 1990s. Both surveys showed that about 70% of the eggs were white, on average. “The first look at the data was sort of anticlimactic,” he said.

Egg masses inside ponds differ in color, either being clear or white.

Credit: Mark Urban, University of Connecticut

But when he looked more closely at individual ponds, there was evidence of more nuanced changes. The team saw that ponds with smaller populations, or fewer egg masses, tended to exhibit large shifts in egg color frequency.

The team decided to test a few evolutionary hypotheses for why this may be the case. Their data showed them that egg mass coloration had evolved in ways predicted by genetic drift. In small populations of less than 100 eggs, egg masses changed a lot between surveys. However, in larger ponds with 100 to 600 egg mases, there wasn’t much change at all. “There seemed to be these random processes driving rapid and drastic population-level changes in frequencies over this short time in the small populations,” he said.

But the team also found this wasn’t the only evolutionary force in play, especially since not all of the eggs in the ponds were one color. “If drift is acting alone, then those small populations should go to fixation through these random processes and just say there,” he said. In other words, they should evolve to being all white or all clear. But that wasn’t the case.

The team thinks another evolutionary process called balancing selection is countering the effects of drift. Balancing selection refers to several different types of natural selection that help prevent the loss of genetic variation in populations. For example, in a process called negative frequency-dependent selection, an evolutionary advantage arises just because a given morph is rare. Because this rare-morph advantage would apply to both color morphs, natural selection in this case counters the effect of drift, pulling populations away from fixation and helping maintain genetic diversity in the population.

Their findings about evolutionary forces are important, Giery said, as is the preservation of genetic diversity in general.

“While we don’t know what it is, there is probably an ecological advantage to being one morph or the other, and that value changes over space and time. Having processes like balancing selection that preserve genetic variation in the metapopulation is important,” he said.

The team plans to look more into whether there is a fitness advantage of one morph or the other. They also hope to identify the gene that causes these two traits.

“In general, I’m hoping this paper stimulates people to look into a lot of questions that have been around for a while,” he said.

The paper also points to the importance of preserving historical records.

“These historical surveys are potentially powerful and useful, but require preservation of data, which is something way rarer than I expected it was going to be,” he said.

Header Image: Evolutionary forces affect the color of eggs that female spotted salamanders lay. Credit: Sean Giery