Share this article

Can internet memes help conserve uncharismatic wildlife?

When researcher Magdalena Lenda was spending long evenings at Australian University, far from her home in Poland, she often waited for her family back home to wake up so she could call them. Just to kill some time, she would scroll through Facebook.

“I looked at news about logging in the Bialowieza Forest, some other news from Poland and some silly content as everyone does on the Internet from time to time,” Lenda said. “I was trying to be up to date with topics that were ‘hot’ in my country.”

One day, one of Lenda’s friend back home sent her a meme — one of those images with text conveying a timely idea that spread virally through social media. This particular meme was a photo of two strange looking monkey with long noses. Lenda went down the meme rabbit hole and discovered a whole page of amusing memes using proboscis monkeys (Nasalis larvatus) to depict themes about everyday Polish life.

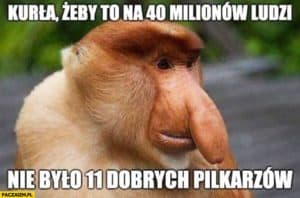

A Polish meme translated to English.

Credit: Nosacze Polskości

“Since then, I was [in] tears from those memes almost every evening,” she said. But Lenda also followed World Wildlife Fund and Greenpeace on Facebook and noticed their memes included more well-known, cute or charismatic animals like pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) or elephants. Those memes had the same number of — or even less — “likes” and “loves” than the monkey memes.

“I also discovered that people who liked amusing memes started discussing serious practical problems with extinction of this species,” she said. “Reading all this inspired me to check if it could be the case this rather silly entertainment could turn into a nonstandard way of informing about the species and basic facts about its ecology.”

In a study that Lenda led published in Conservation Biology, she and her colleagues set out to find if memes of not so charismatic species, like proboscis monkeys, gain conservation support.

The team first checked people’s interest in proboscis monkeys in Google Trends for Poland as well as in the rest of the world. They also looked at trends for well-known animals typically used in WWF charities. “In Poland, the proboscis monkey was almost as popular as panda and koala,” Lenda said. “It was much more popular than any other well-known monkey.”

Elsewhere in the world, though, proboscis monkeys were far less popular on the Internet than well-known species like koalas, pandas, macaques, gorillas or orangutans.

The team then looked at how the peaks for searching the proboscis monkey in Google Trends in Poland matched to the time when Polish memes began appearing on the internet. “We found that it matched closely,” she said. “Amusing memes appeared in late 2016, then become the most popular in 2017 and 2018. The popularity of memes and their number on the internet correlated with the trend in Google Trends.”

This meme, created after Poland lost a 2018 World Cup match, reads in English: “Oh no, we have 40 million people in Poland and we can’t find even 11 good football players among them.”

Credit: Nosacze Polskości

The researchers then compared the numbers of “likes” on Polish memes of proboscis monkeys with photos from WWF and Greenpeace that usually included photos of sad animals or cute species without amusing text. “We found that amusing memes gained more or similar number of “likes” on Facebook as pictures of cute animals presented by WWF of Greenpeace,” she said. “They gained also more “loves.” Facebook likes and emoticons are considered as indices of popularity.”

Finally, Lenda and her colleagues looked at public donation events and found the same people who started the profiles with proboscis monkey memes also began some small fundraising actions. “The funds were collected by completely unknown people, with no documented connection with nature conservation, and such actions always arouse some reserve and distrust, despite the noble purpose,” she said. “Nevertheless, the fact that several hundred people have made individual decisions to support the conservation of proboscis monkey, while they could choose another, more well-known charity event, or spend money on a cinema ticket, deserves attention.”

Lenda said the research is only correlative, so more research should be done by marketing specialists. “However, it is definitely worth trying to apply humor in actions promoting nature protection,” she said. “In our work, we suggest that specialists responsible for conservation marketing could try to keep up with emerging popular content related to nature (species, regions) in online communities.”

Header Image: Polish memes often include the proboscis monkey. Researchers recently found the use of their photos has increased searches for the monkeys as well as donations for their conservation. Credit: Peter Gronemann