Share this article

TWS Position Statement: The North American Model and the Future of Wildlife Conservation

Back to Position Statements page

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation (The Model) is a set of laws and policies that emerged over more than a century and collectively distinguished wildlife conservation in Canada and the United States from other forms worldwide. The Model established the following seven principles (the Seven Principles):

- Wildlife as Public Trust Resources;

- Elimination of Markets for Game, Songbirds, and Shorebirds;

- Allocation of Wildlife by Law;

- Wildlife Should be Killed Only for a Legitimate Purpose;

- Wildlife Are Considered an International Resource;

- Science is the Proper Tool for Discharge of Wildlife Policy; and

- Democracy of Hunting.

The Model provides a historical perspective on the development of modern wildlife conservation and management in the United States and Canada. The Model captures critical benchmarks in the field of wildlife conservation such as the 1842 United States Supreme Court ruling in Martin v. Waddell, and its 1896 ruling in Geer v. Connecticut, which laid the groundwork in U. S. common law for the principle that wildlife resources are owned by no one, to be held in trust by the government for the benefit of present and future generations. This law underpins the concept of democratization of hunting in which all residents have the right to hunt and fish within the bounds of scientifically established regulations. Hunting in the United States and Canada has remained open to all residents regardless of class, with hunting remaining important to wildlife management in contrast with many other conservation systems abroad. Both Theodore Roosevelt and Aldo Leopold hailed what they termed “democracy of sport” as a distinguishing feature of wildlife conservation in North America.

Conflicts between sport hunters and market hunters also led to advocacy by the former for elimination of markets for game and shorebirds, allocation of wildlife by law rather than privilege, and restraint on the killing of wildlife for anything other than legitimate purposes. Similarly, a movement led by women bird enthusiasts and clubs, largely state Audubon chapters, along with other conservation leaders, led to the prohibition of hunting birds for the millinery trade. Supported by the advocacy of these groups concerned with the dramatic declines in wildlife, the Public Trust Doctrine became a legal bedrock for state and federal authority over wildlife in the United States. In Canada, alarm over the declines south of the border also led to governmental protection of wildlife at provincial and federal levels. The subsequent collaboration of wildlife conservationists in the U.S. and Canada led to treaties establishing fur seals and migratory birds as international resources. The Migratory Bird Treaty was signed by the United States and King George V for Canada in 1916, and later by Mexico (1936), Japan (1972), and Russia (1976), which expanded the international scope of bird conservation. Other international agreements protecting wildlife have followed, including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), recognizing wildlife as an international resource.

Increased recognition of the importance of science in directing wildlife management led to implementation of the 1930 American Game Policy in the U.S., as adopted at the 17th American Game Conference, and the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937. The development and implementation of these conservation principles in the United States and Canada, with their scientific foundations, led to increased professionalization of wildlife conservation programs. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, societal concerns over international trade in wildlife and the conversion and loss of wildlife habitat that resulted in accelerating loss of species led to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 in the United States and the Species at Risk Act (SARA) of 2002 in Canada to conserve species, genetic diversity, and ultimately biological diversity. Important conservation provisions began to be added to Agricultural legislation as early as the 1930s with especially important additions (Swampbuster, Sodbuster, Conservation Reserve Program) to the Farm Bill in the 1980s.

Professor Valerius Geist created the concept known as The Model in response to challenges to public ownership of wildlife and the consequences he foresaw. The Model was never intended to capture the full suite of policies and practices that characterize conservation in the United States and Canada. Rather, it identified those rooted in treaty, law, and broad-based policy that in combination represent a unique North American approach. This Position Statement describes the role of the Seven Principles in establishing TWS policy and developing additional policy that may transcend the original tenets of the Seven Principles.

The Model’s relevancy to the current state of wildlife conservation in the U. S. and Canada is often criticized or called into question. The Model’s Eurocentric foundations do not capture societal changes or changes in the values of wildlife professionals. Moving forward, it is important that established principles are implemented across the wildlife profession, and the principle of democratization must be expanded to include enjoyment and use of wildlife by all people. The Model has been focused largely, but not exclusively, on game species; hence, application to broader taxa is needed.

The laws and policies represented in The Model did not explicitly address management of wildlife on lands of sovereign indigenous peoples or recognize either formally established treaty rights or traditional subsistence uses by indigenous peoples. Acknowledgement that indigenous rights and traditional use do not necessarily recognize political boundaries has led to formal co-management agreements in Alaska and in some areas of Canada for conservation and management of wildlife. Efforts to enact new laws and policies must include indigenous perspectives, experience, and knowledge.

Narratives about The Model have arisen that inappropriately drive a perception that The Model is primarily associated with management of wildlife to benefit hunters. While hunting clearly played an important historical role in the development of key laws and treaties to benefit wildlife, wildlife management for the sole or primary benefit of hunters is not supported. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, for example, was strongly motivated by the importance of conserving songbirds and shorebirds. That said, more explicit recognition that the laws and policies described in The Model are applied to nongame and endangered species as well as those that are hunted or trapped will greatly improve The Model’s relevancy. It is also key to recognize that the ecosystems that support wildlife are key to their conservation. Impacts from humans on wildlife populations and their habitats will require expanding collaborative conservation efforts by all people that depend on, or otherwise value wildlife across all continents. It is, therefore, important to increase the diversity of people involved in wildlife-related activities, in line with the principle of democratization of hunting. Hunters have traditionally been and remain an important source of revenue for conservation, but consistent with the principle of democratization of wildlife it is important to create new avenues of funding for wildlife and habitat conservation.

The policy of The Wildlife Society, in regard to the conservation of wildlife in North America is to:

- Promote and support concordance between the laws and policies of municipal, state, provincial, federal, and tribal governments, and the core principles of wildlife conservation in North America.

- Advocate for new laws and policies necessary to address current and emerging conservation challenges, while considering the following:

- Recognizing and integrating the role of indigenous perspectives and the cooperative or co-management of wildlife among sovereign indigenous governments and those of federal, state, provincial, and municipal entities;

- Supporting access to public lands for responsible wildlife-related activities;

- Continued and expanded conservation of all taxa on public and private lands;

- Recognition of increasing threats and the critical value of habitats and ecosystems in supporting the conservation of populations of fish and wildlife;

- Expansion of opportunities for a broader range of people to gain exposure to wildlife-related activities.

- Protecting existing sources of funding and establishing expanded funding sources for wildlife management and conservation based on a diversity of wildlife-related activities and the people that enjoy them.

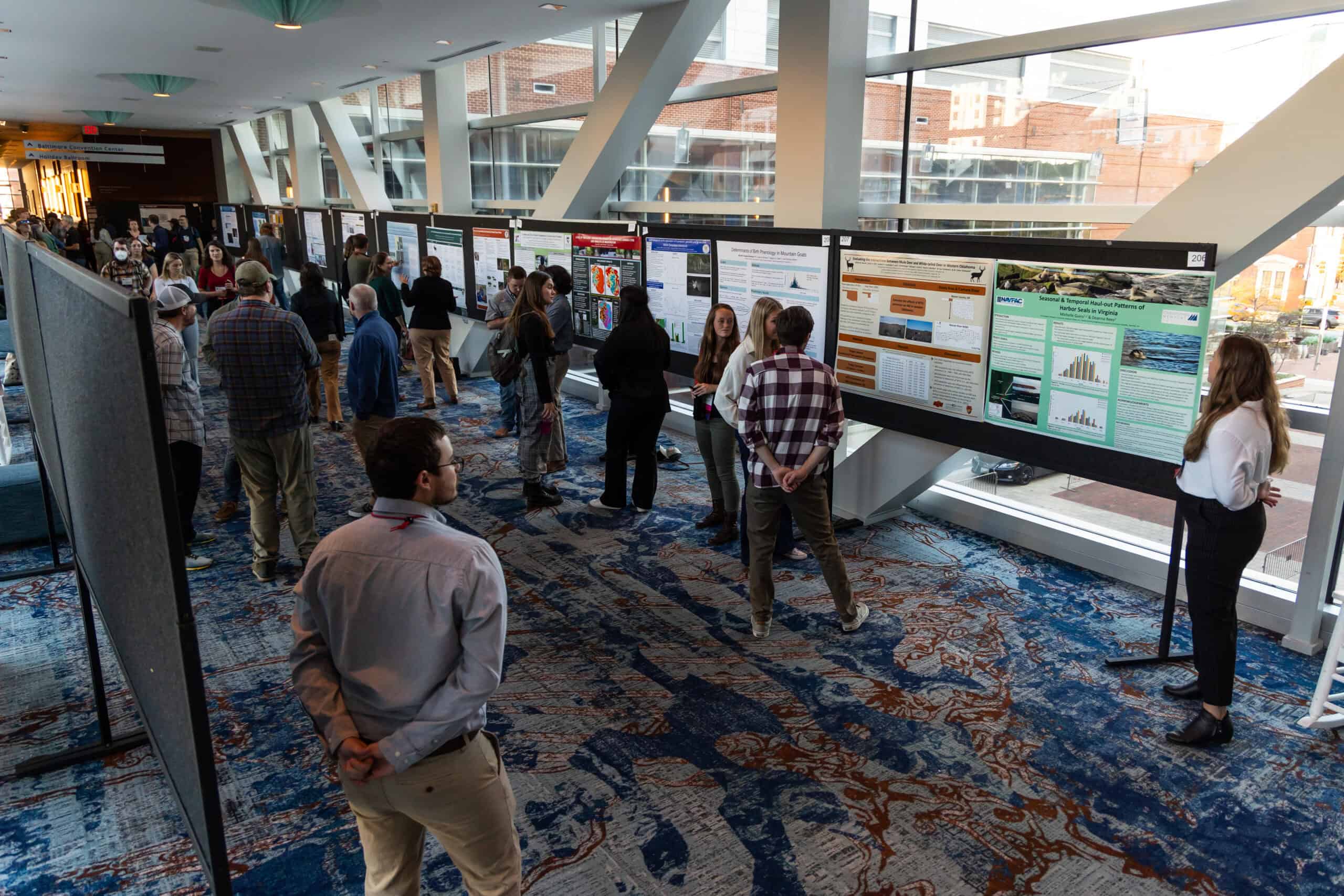

- Foster educational opportunities to increase awareness of the breadth of the Seven Principles as expanded in this document for conservation of all wildlife among wildlife professionals, wildlife students, and the broader public.

- Support the identification of threats and challenges to each of the Seven Principles as expanded in this document, and as appropriate, use the diverse scientific and educational resources of the Society to address these threats.

Approved by Council November 2024

North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Position Statement pdf