Share this article

Every person matters for this year’s Aldo Leopold winner

It was the fall of 1943, and a young Leigh Fredrickson joined his father for a day in a Missouri River oxbow in Iowa collecting cattail leaves. A cooper, his father needed the leaves to seal oak barrels he was making for a meat-packing house.

But it was more than the cattail leaves that drew his interest. Fredrickson, who is now retired as a fisheries and wildlife professor at the University of Missouri and director of the Gaylord Memorial Laboratory, loved the direct exposure to a wetland system. “I was so taken by the habitat and representative birds, bugs and herptiles,” he said.

Fredrickson enrolled in Iowa State College’s engineering program, but that didn’t last. When a professor screened an oil company film showing bulldozers pushing over cypress trees, Fredrickson was appalled.

“I made my decision,” he said. He switched his major to fish and wildlife management to protect the sort of environments he had seen the bulldozers destroy.

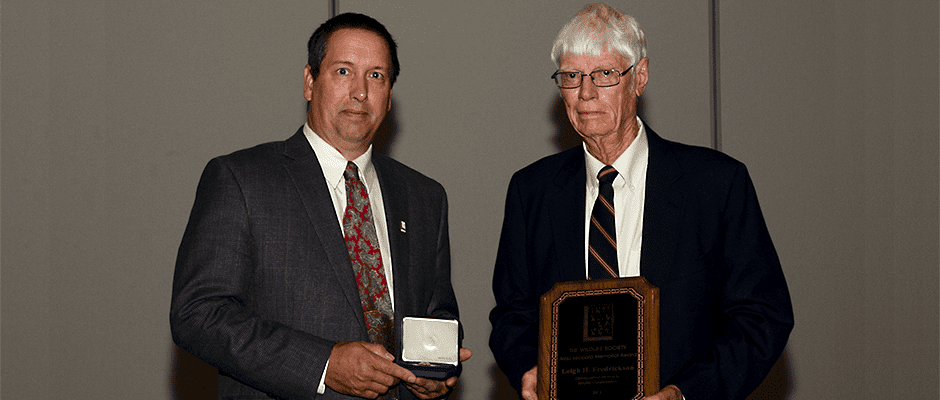

Fredrickson’s love for wildlife and the outdoors has followed him throughout his life. A member of The Wildlife Society since 1959, Fredrickson won the 2018 Aldo Leopold Memorial Award, the greatest honor bestowed by The Wildlife Society.

After earning a master’s and PhD degrees, Fredrickson accepted the directorship of the Gaylord Laboratory in southeastern Missouri, a position he held from 1967 to 2002. The lab was part of a cooperative agreement between the University of Missouri and the Missouri Department of Conservation with a focus on waterfowl ecology and access to 28,000 acres of swamp habitat.

Initially he studied nesting wood ducks (Aix sponsa) and hooded mergansers (Lopodytes cucullatus), tagging thousands of day-old ducklings. He found many female wood ducks had two successful broods each year, and some were consistently more productive than others. Hooded mergansers, he found used swamps very differently than wood ducks.

But Fredrickson’s work didn’t stop with wetlands. In 1970, he worked at Hallett Station in Antarctica in 1970, helping clean up aviation fuel and researching penguins. Penguin biology stimulated his thinking about birds back home. He returned to research how long-distance migrant waterfowl acquired and used energy — knowledge that aided managers in decision-making. Fredrickson went on to testify in court cases, providing his expertise on issues such as baiting, chemical contamination and wetlands.

Throughout a career spanning over 50 years, Fredrickson contributed greatly to knowledge about wetland and waterbird ecology as well as management and conservation of wildlife and wetlands. He gives much credit to the many he met who provided encouragement, support, mentoring, collaboration and provided him key experiences throughout his career, many of whom were former Leopold recipients.

An important part of his work is sharing insights with others, whether that’s helping landowners or managers implement management and conservation actions or guiding students interested in the field. He has mentored 79 graduate students in wildlife biology and was one of the first professors to direct female graduate students. Teaching waterfowl ecology and wetlands at the University of Missouri, Fredrickson took students on multi-day field trips to expose them to diverse landscapes and meet professionals passionate about caring for these sites.

During his career, he visited over 300 national wildlife refuges as well as state and private wetlands in all 50 states to share his wetland perspective. Fredrickson and his team of students and professionals collaborated to conduct wetland workshops to expose professionals to the dynamics of wetland systems over several decades. And although he’s retired, his work still isn’t done. This year his team conducted workshops in seven states and Mexico. He is currently working with Mexican colleagues to develop wetland and waterbird programs at the southern terminus for many northern nesting species. He recently aided in developing a national waterbird census for Mexico by coordinating with active and retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service pilots and biologists to educate survey pilots and observers on how to conduct ground and aerial bird counts.

Throughout his career, Fredrickson said, he’s learned that every person matters. “In the academic arena a common focus is to seek students with impressive grade points and GRE scores,” he said. Those may be important factors for research scientists, Fredrickson said, but research isn’t everything. “A vast array of wildlife professionals” is needed, he said, to apply research to a disrupted environment.

Header Image: Leigh Fredrickson won the 2018 Aldo Leopold Memorial Award. ©TWS