Share this article

WSB: Which wildlife-friendly fences work for pronghorn?

During a 2003 radio telemetry study, researchers inside helicopters took photographs of pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) capture events.

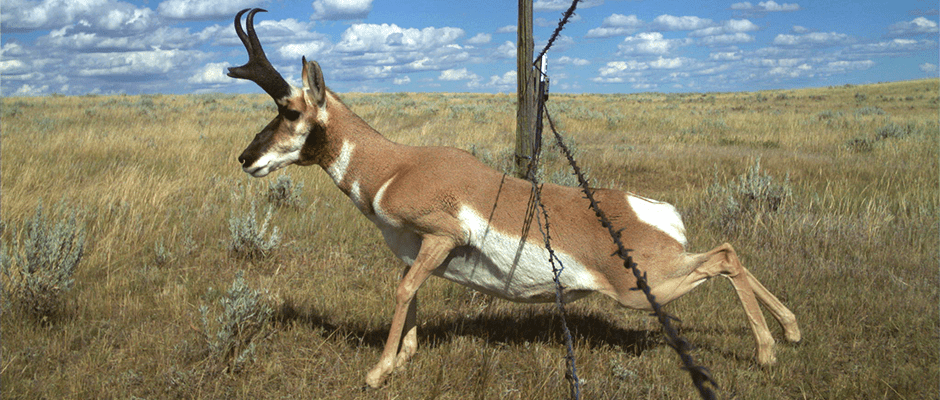

After reviewing the photos, they were surprised to find a pronghorn doe missing hair all over its back, with scratches on its skin. “Its rump was really black, almost like it was frostbitten,” said Paul Jones, a senior wildlife biologist with the Alberta Conservation Association. “We attributed that hair loss to crawling underneath fences.”

While some landowners have been using wildlife-friendly fence modifications to mitigate the issue and there’s been anecdotal evidence that they work, Jones realized there hadn’t yet been a study testing the effectiveness of the fence modifications. He led a study looking at these fences published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

In the study, Jones and his colleagues tested the effectiveness of using a few different devices on standard pasture fences used to control domestic livestock. They tested clips used on the bottom wires of the fences to allow room for pronghorn to crawl underneath, and goat bars — pieces of PVC pipe covering the bottom two wires of the fences, named after the nickname for pronghorn, “speed goat.”

A pronghorn exhibits hair loss and cuts from crawling underneath a fence. ©Alberta Conservation Association

The researchers placed trail cameras in areas where fences had these treatments, at a site where pronghorn were suspected of crossing the fence had smooth wire and a control site where there was no treatment. They then monitored which sites the pronghorn used.

Clips and smooth wire worked best, the researchers found, and 18 inches between the bottom wire and the ground was optimal to allow pronghorn to pass underneath. Pronghorn didn’t prefer to use fences with goat bars, they found.

With funds and time available, Jones suggests replacing the bottom barbed wire on fences with smooth wire, and making sure the bottom wire is 18 inches above the ground for pronghorns to cross. Without time and finances available, he suggests landholders use clips.

When pronghorn are unable to cross, Jones said, it affects their seasonal use of areas and access to forage in their home ranges. It can be particularly impactful for pronghorn, he said, because they are partially migratory.

Jones is passing on information to landowners regarding fencing recommendations. He plans to further study wildlife-friendly fencing, looking at sage grouse reflectors that signal to the grouse to fly over, as well as goat bars at the top of the fence that elk and deer may use to jump over.

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper in the Wildlife Society Bulletin. Go to Publications and then Wildlife Society Bulletin.

Header Image: A pronghorn buck under a smooth wire fence. ©The Nature Conservancy & University of Montana