Share this article

Mortality Survey Shows Leading Causes of Bat Deaths

White-nose syndrome (WNS) and wind turbines have killed the largest number of bats in the world since 2000, according to a new study.

Little brown bats in a NY hibernation cave. Note that most of the bats exhibit fungal growth on their muzzles. ©Nancy Heaslip, New York Department of Environmental Conservation

“Many of the 1,300 species of bats on Earth are already considered threatened or declining. Bats require high survival [rates] to ensure stable or growing populations,” said Tom O’Shea, a USGS emeritus research scientist and the lead author of the study published in Mammal Review in a release. “The new trends in reported human-related mortality may not be sustainable.”

Coauthor Raina Plowright, an assistant professor at Montana State University, said they looked through literature dating back to 1790, recording any time in which more than 10 bats died at the same place within a year’s time as a mass mortality event. They compiled nearly 1,200 of these events from around the world and found that prior to 2000, most of the bats were intentionally killed by humans.

Many of the deadly actions were due to dangers people perceived. On the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, for example, inhabitants kill fruit bats to stop them from eating local fruit crops. In South America, ranchers sometimes cull vampire bats because they believe the animals pass rabies along to cattle.

But after the turn of the millennium, wind turbines and WNS became the leading causes of death.

The cover feature story in the spring 2015 issue of The Wildlife Professional examined the effect of wind energy on bats, among other things. Paul Cryan, a research biologist with the USGS and also part of the recent Mammal Review study, said in early 2015 that research showed the hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) accounted for 40 percent of all wind turbine-caused bat deaths in the United States and Canada. He believes that the bats might be confusing the turbines with trees where they roost, hunt insects and socialize with other bats.

Insect-eating Brazilian Free-Tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) provide a great pest-control service to agriculture and natural ecosystems. ©Paul Cryan, USGS.

WNS has so far predominantly affected bats in North America, wiping out entire populations of the small creatures in the East, but still accounts for one of the leading causes of mass bat mortality globally. Wildlife managers released the first successfully treated bats for the fungal pathogen in Missouri last May, but Plowright worries that even if researchers find a way to stop the spread of the disease, bats will still face trouble.

She said that unlike other small mammals, bats live for many years and are slow breeders, with many species only giving birth once a year.

“They are not evolved to respond really quickly to a mass mortality event,” she said. “It’s quite a worry to see these mortalities in bat populations because they won’t be able to recover these numbers.”

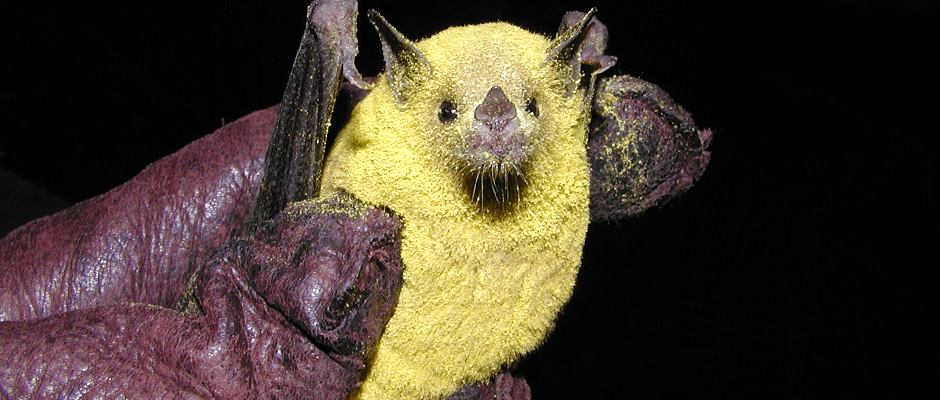

Header Image: Long Nosed Bat — A long-nosed bat covered with pollen, probably from a cactus flower. ©Ami Pate, National Park Service