Share this article

Entomologist Describes 74 New Volcano Beetle Species

To find 74 new species of beetles, you need to go through an experience.

For Jim Liebherrr, this meant flying in a helicopter to the remote rainforests on the slopes of Haleakala volcano in the Hawaiian island of Maui in near constant rainfall then beating plants and trees with a stick — often at night — so that insects would fall out of the tree.

“It’s got to be one of the best experiences of my life,” said the entomology professor at Cornell University and lead author of a new study published in Zookeys. “You know that everything that you’re finding, it might not be a new species but it’s new. Nobody’s tried this before.”

Liebherr has been on a mission since 1991 to determine what kind of insects live in the rainforests of Hawaii in an effort to provide baseline knowledge for assessing future changes to the ecosystem.

A moss covered ohia tree in Maui rainforest with a Mecyclothorax rex beetle inset. Image Credit: James K. Liebherr

Usage Restrictions: CC-BY 4.0

Over the years he and other researchers spent several hundred days collecting more than 7,600 specimens of beetles he specialized in — Mecyclothorax. Many related species in the mainland United States are ground beetles but the majority of the ones on Haleakala live in trees — perhaps spending their entire lives in a single plant. Most of the Hawaiian beetles are nocturnal and search for prey or mating opportunities on acacias, Hawaiian ohias and other trees and ferns.

To catch the bugs, Liebherr would often team up with other entomologists to survey remote areas of the roughly 550-square mile Haleakala area. They would shake plants or hit tree moss with sticks to make the insects rain down onto sheets, where they would then be collected and stored in specimen vials.

“Mosses on the trees can grow to be six inches thick. These moss mats are probably a hundred years old — they’re entire condos of insects,” Liebherr said. When it wasn’t raining, there was often a fog that contributed to a sense of constant dripping in the forest.

“It can get monotonous but you know you have to do it. It’s not a day at the beach — it’s sampling.”

The dividing characteristic isn’t that easy to spot, though. Many distinct species rely on the same diet of small arthropods like caterpillars, spiders or possibly snails and don’t appear different to the naked eye. But species on opposing sides of a valley or separated by lava mudflows had a major difference when it came to more private parts of their anatomy — the male genitalia.

It’s unclear exactly how long these beetles have been on the island, but the ancestor beetle species probably came across from Australia no earlier than 1.2 million years ago, or about the time the volcano first popped out of the ocean. This means that they evolved into new species relatively rapidly, Liebherr said. These 74 new species he describes in this paper are among the 116 total species on this volcano alone.

As many of its native bird species become extinct due to habitat loss, diseases like avian malaria and the spread of invasive species, Liebherr said that the state is increasingly trying to promote the idea of using its insects as indicators for ecosystem change: “You can use the insects as indicators of habitat health because they’re still around.”

But before they can do this, more work like Liebherr’s needs to be done to access what’s out there.

“If we understand these communities better, we can figure out how they work,” he said.

During the 1890s R.C.L. Perkins, a British entomologist, surveyed some of the same areas and found many of the same insects that Liebherr found. But some of the ones from a century ago didn’t turn up in Liebherr’s survey, giving us a century-long snapshot of how things have changed in the area.

Liebherr dreams that someday people will come back to the same areas in 100 years and conduct the same searches with the same methods he used to see how things have changed — if they have changed, that is.

“As long as the plant communities are stable, the insects should be stable. But invasive plants may be the undoing of native forests we see today.”

If researchers dig a little deeper in these remote areas, they are also likely to discover more new species as well — with these beetles and possibly with other insects.

“I’ve taken a bunch of steps in knowing what’s out there, but we are by no means done.”

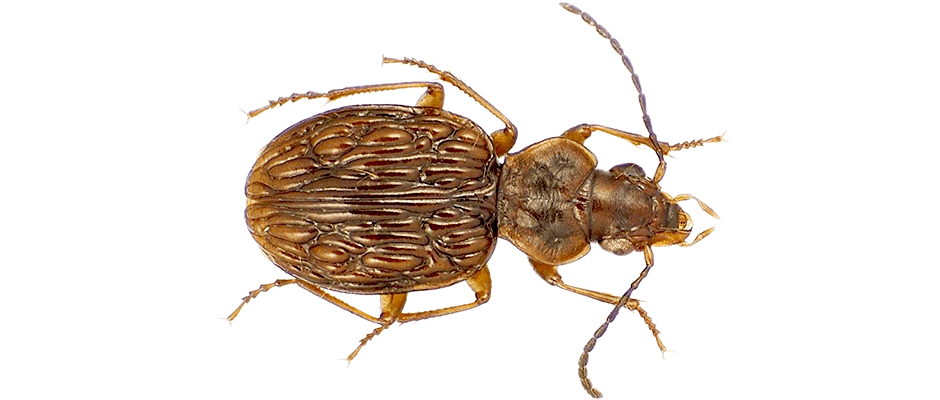

Header Image:

Mecyclothorax medeirosi, a species that lives in Hawaiian rainforest, named to honor Art Medeiros, a renowned conservation biologist and project collaborator from Maui. Image Credit: James K. Liebherr

Usage Restrictions: CC-BY 4.0