Share this article

35-year study sheds new light on alligators’ lifespan

American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) can live as long as humans, making it difficult for scientists to conduct long-term studies on them. But Phil Wilkinson, a retired manager of South Carolina’s Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center and biologist with the state Department of Natural Resources, has been studying the species since the 1970s, creating a dataset from over 35 years of research. Some of his findings, recently published in the journal Copeia, upend common wisdom about how alligators grow and age.

“To my knowledge, there’s no other crocodilian study like this in the world,” said Thomas Rainwater. A research scientist and wildlife research coordinator with the Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center and Clemson University’s Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science. Rainwater is the second author on the paper. “It’s remarkable to have such a long-term dataset on the same population,” he said.

For the study, a research team collected and reviewed 35 years’ worth of data on alligators at the wildlife center in Georgetown, S.C. Over the years, researchers had captured, marked, and measured hundreds of alligators and collected blood, urine and skin samples for a variety of projects.

What they uncovered overturned some conventional wisdom about alligators. Biologists had long believed the animals continued to grow throughout their lives, but Wilkinson’s studies called that into question. In 1993, he began observing that some of the animals reached a point where they stopped growing. After reviewing measurements from over the years of his research, the team found that many animals reached their maximum size at around 25 to 35 years of age. Rainwater said this growth pattern — called determinant growth — has been observed in some other crocodilian species such as freshwater crocodiles in Australia and caiman in Brazil, but it hadn’t yet been reported for wild alligators.

The team also found females continued to reproduce for many years after their linear growth ceased. In one case a female estimated to be about 68 years old was still nesting in 2014 and produced a fertile clutch of eggs. Previous literature reported that middle-aged females are the most fertile, Rainwater said, but this finding suggested that either older females can also produce fertile clutches or an alligator’s middle age is older than originally thought.

“We’re trying to uncover the answers to these questions,” he said. “We’re hoping to keep the project going for many more years.”

Rainwater hopes knowledge about Yawkey alligators will aid general alligator conservation. Although these alligators live in a 15,000-acre preserve where hunting is banned, he said, the research can provide baseline knowledge about patterns of growth and aging to compare with alligators outside the preserve where hunting is allowed.

“Removing large numbers of adults from the population is often unsustainable,” Rainwater said. Alligators exhibit low survivorship of eggs, hatchlings and juveniles, he said, but high survivorship among adults, and their delayed sexual maturity makes them particularly critical to maintaining the species.

“South Carolina is trying to be conservative about the number of alligators that are allowed to be taken during its annual public hunting season,” he said. “State biologists need more data to make informed decisions on these issues, and studies like ours and others will help provide this information.”

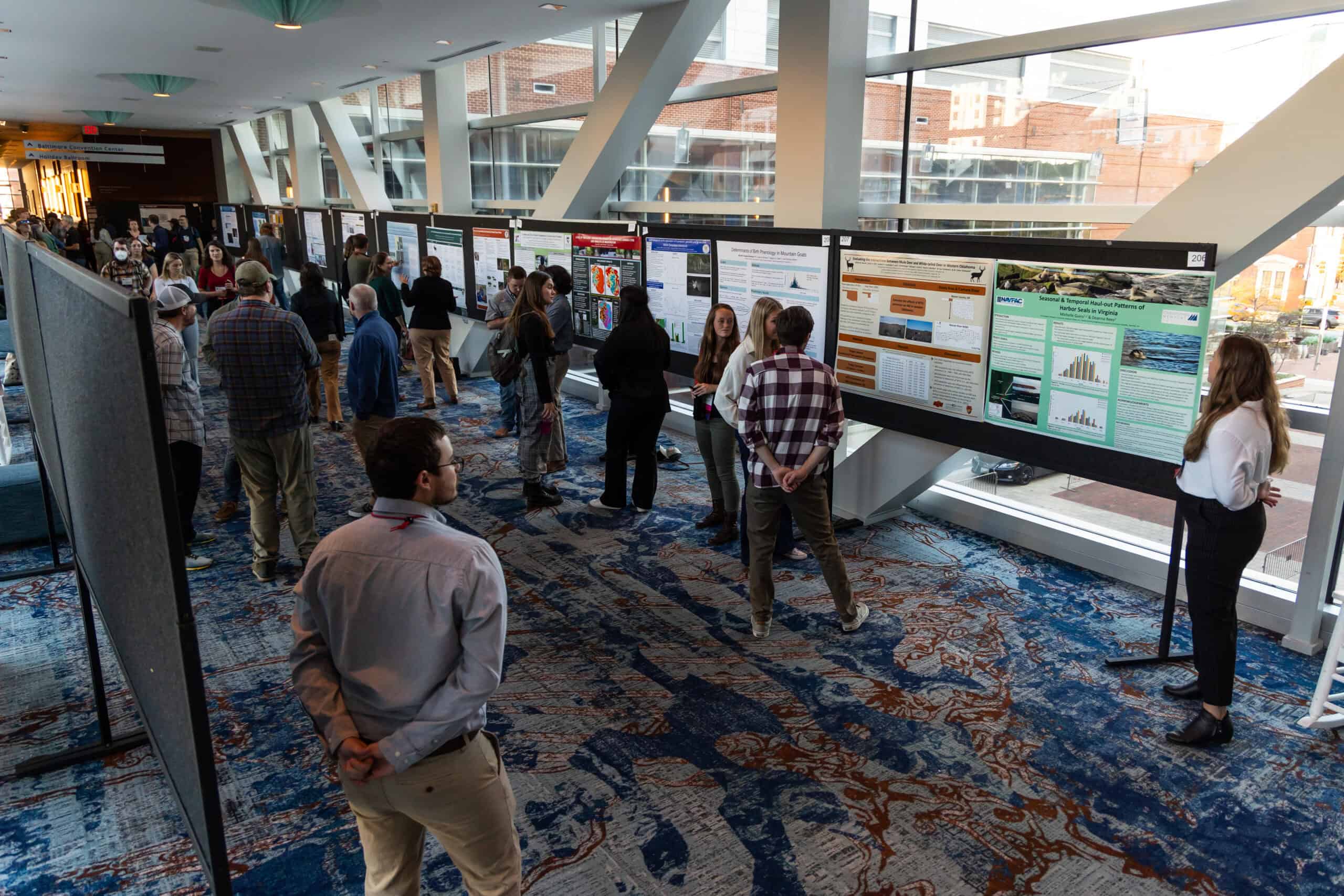

Header Image: Researchers measure an adult female alligator that they captured in Yawkey Wildlife Center. ©Anna Munoz