Share this article

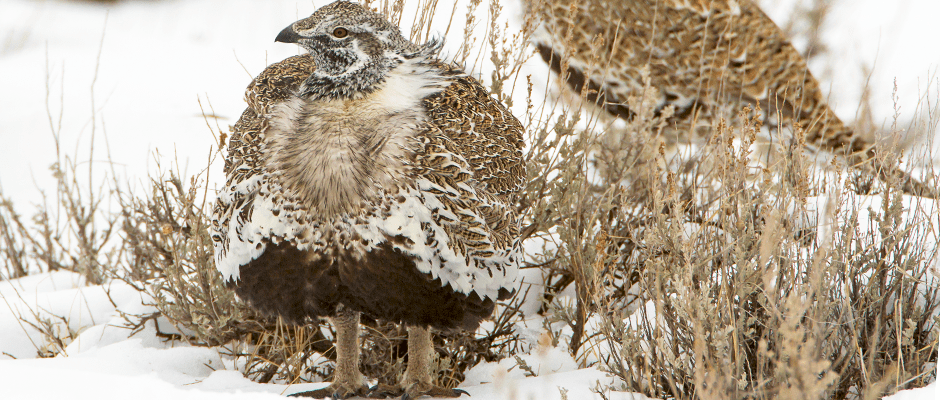

JWM study: Greater sage-grouse use ‘stepping stones’ for long migration

About 10 years ago, researchers using VHS telemetry were surprised to find greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) traveled 240 kilometers between Saskatchewan and north central Montana — the longest documented migration of any grouse.

With the newer technology of GPS collars, researchers were recently able to determine more specific information about that journey. They found that the birds were not just making one straight shot to their migratory habitats. Instead, they were using “stepping-stone” behavior, using frequent stopover sites, similar to the behavior of migratory big game populations such as mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus).

That’s possible, they found, thanks in part to Montana’s conservation of sage-grouse core areas, the Bureau of Land Management’s sagebrush steppe rangelands and private land easements that protect the bird’s migratory pathways.

“They’ve done a fantastic job of encompassing migratory pathways,” said Jason Tack, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Habitat and Population Evaluation Team (HAPET) office, and a coauthor of the recent study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management. “Continuing to work across fences in this landscape will be critical in maintaining migration for a suite of species.”

He and his colleagues captured sage-grouse on leks during their breeding season and fitted them with GPS collars. The GPS technology relayed four locations per day, every six hours.

“What motivated this study was the how, when and where of migration in order to make sure it was working in this landscape,” said Tack, A TWS member.

Tack was also interested in finding out how the birds reacted to extreme winter weather over the course of the study. “It was the most snowfall we had seen in 30 years,” Tack said. Through GPS data, the team observed that sage-grouse made a detour about 64 kilometers south of their usual migration route, using rugged habitat more typically used by bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis).

“We suspect it was the only sagebrush available in that landscape,” he said.

Sage-grouse preferred gently rolling grassland and sagebrush flats, the team found, using private and public lands but avoiding cropland. During autumn migration, they spent a day at an average of nine different stopover sites while traveling 41 to 126 kilometers in 14 days.

Tack is currently working on further research to determine overlaps between sage-grouse and pronghorn (Antilocapra Americana) migration, which he hopes will also provide further conservation implications for both species.

Header Image: Two greater sage-grouse stand in the snow during their 240-kilometer migration. ©John Carlson