Share this article

WSB: Seeking bullets lethal to small mammals, not scavengers

At MPG Ranch, a conservation ranch in Montana’s Bitterroot Valley, most of the golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) wintering on the property have elevated concentrations of lead in their blood. Much of that probably came from lead ammunition used to hunt big game, biologists figured. If a deer or elk is shot but the hunter doesn’t recover the animal, or if bullet fragments remain in a gut pile left behind, scavengers that feed on the carcass or gut pile can ingest the lead, leading to possible health impacts and sometimes death.

Lots of studies had already looked at big-game hunting and lead poisoning. But what about the shooting of squirrels, prairie dogs and other small mammals? These animals are hunted recreationally and shot by farmers as pests, but state laws don’t require their carcasses to be removed, as they do for big game.

“We were curious if that was possibly a vector for raptors accumulating lead,” said Michael McTee, an environmental scientist at MPG Ranch, where biologists from Raptor View Research Institute, a nonprofit raptor research organization based in Missoula, found 89 percent of the golden eagles on the property had elevated lead concentrations.

McTee and his team set out to see if some lead bullets might carry less risk of poisoning scavengers than others, and if nonlead bullets, often made of copper, would be effective against small game.

“The way we looked at this was from a skeptic’s perspective,” said McTee, lead author of the study in the Wildlife Society Bulletin. He suspected some types of lead bullets would result in more fragmentation than others and pose greater risks to scavengers. Overall, however, his team found that all of the lead bullets included in the study could poison scavengers, although some bullets pose more of a risk than others.

“If you use lead rounds at all, there’s going to be a risk of poisoning scavengers,” he said.

Columbian ground squirrels are often shot for recreation and damage control on farms and ranches. ©Jeff Clarke

Nonlead bullets, on the other hand, proved to be just as lethal to small game as lead bullets, without the risk to scavengers. “This shows you can use nonlead rounds,” McTee said. “They work well.”

In May 2016, McTee and his team looked at what happened when shooters at ranches in Montana and Idaho controlled populations of Columbian ground squirrels (Urocitellus columbianus) by shooting them with three types of rifle — a .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire, a .22 long rifle and a .223 Remington — using both expanding and nonexpanding lead and nonlead rounds.

They found all types of lead bullets left lead in at least a third of the squirrels. They expected fragmentation would be higher in expanding bullets, but in the .17 HMR, the variability in fragmentation was so high, the estimated lead concentration was the same. Squirrels shot with expanding ammunition in the .17 HMR and .223 Rem rifles showed the highest lead levels.

But what about the nonlead bullets?

“One thing we wanted to address with this study was, do nonlead rounds work as well as lead rounds?” McTee said. “A lot of people are concerned about the performance of nonlead ammunition.”

The nonlead rounds, they found, proved to be just as effective at incapacitating the squirrels, at a cost only slightly higher than lead rounds.

“Our results indicate that nonlead bullets eliminate the risk of additional lead exposure to scavengers while maintaining the lethality of lead bullets,” they concluded.

The study didn’t include copper .22 bullets, which weren’t available at the time, but McTee said they are available now and likely to be just as effective.

With recreational shooters, farmers and ranchers taking millions of small mammals each year, McTee said, he hopes they consider nonlead rounds as an alternative.

“Maybe one day we won’t see so many eagles with elevated levels of lead at MPG Ranch,” he said.

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper on early view in the Wildlife Society Bulletin. Go to Publications and then Wildlife Society Bulletin.

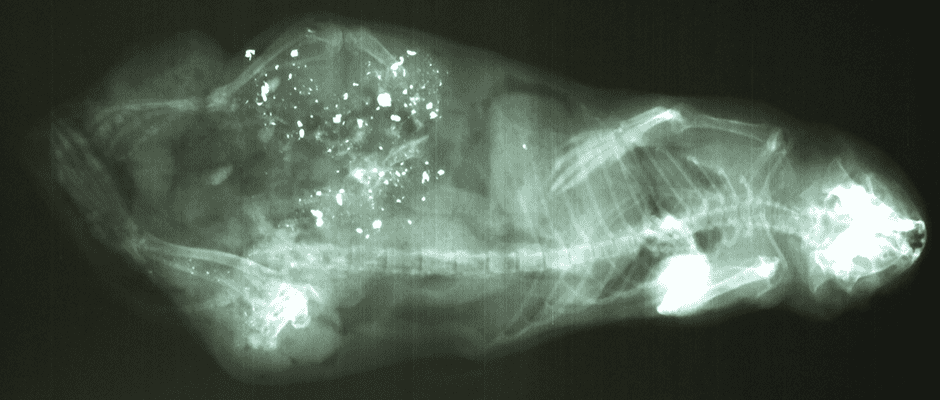

Header Image: A radiograph of a Columbian ground squirrel shot with a .17 HMR rifle reveals a constellation of bullet fragments. ©Sapphire Animal Hospital