Share this article

Steps to managing climate change refugia for wildlife

Managing wildlife in the face of climate change is a Herculean task, but focusing on climate change refugia can be one way to help ease the pressure.

As part of that effort, researchers, for the first time, have developed an outline for resource managers to use climate change refugia — areas that appear largely unaffected by climate change — to protect wildlife. Climate change refugia also allow species to persist despite surrounding climate change issues. The scientists recently published their research in PLOS ONE.

“The main purpose is to make it tangible to managers — to take this concept and make it something you can enact on the ground,” said Toni Lyn Morelli, U.S. Geological Survey Research Ecologist with the Northeast Climate Science Center and the lead author of the study.

Morelli and her colleagues tried to determine what information is needed to identify refugia as well as what refugia look like. As part of the study, about 15 people including physical scientists, climatologists, ecologists and resource managers met for three days to synthesize the current literature on these lands and identify and fill current gaps.

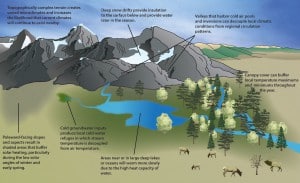

Different examples of climate change refugia, or areas that are likely to experience reduced rates of climate change. ©Toni Lyn Morelli, PLOS ONE

In the paper, the researchers presented a framework called the Climate Change Refugia Conservation Cycle that walks managers step by step through potential ways to tap into climate change refugia to protect wildlife. For example, Morelli says prioritizing conservation of these areas is important. “Ultimately, we hope that this can be information they can use when they’re prioritizing actions on the ground for climate adaptation,” Morelli said. “We know managers have to base their decisions on a number of things … I’m not saying this is the ultimate answer. But it’s a short-term solution while we work on finding long-term solutions to climate change.”

Morelli says colleagues’ work has shown that climate change refugia could help wolverines return to California since the females need a certain depth of snowpack to den. As a result, identifying refugia where snowpack is maintained on the landscape and is deeper than other places could help the species. Similarly, as part of her research at UC Berkeley, Morelli found that Belding’s ground squirrels (Urocitellus beldingi) used meadows that were identified as refugia.

“For us, we think about this as a hopeful message for trying to provide opportunities for managers,” she said. “It’s difficult to be managing in the face of climate change. This is another tool at their disposal and we hope it’s useful for them.”

Morelli and her colleagues are now working on making the information from this study more accessible to managers. Next week, she’s leading a workshop at the IUCN World Conservation Congress to pilot the climate change refugia conservation cycle with conservation practitioners from around the world. “We’re hoping we can formalize it for managers to use on a day-to-day basis.”

Header Image: Some Sierra Nevada meadows, like this one in Yosemite National Park, have been identified as climate change refugia that managers can protect to help conserve wildlife in the face of climate change. ©Toni Lyn Morelli