Share this article

Skipping the layover, Arctic geese opt for a direct flight

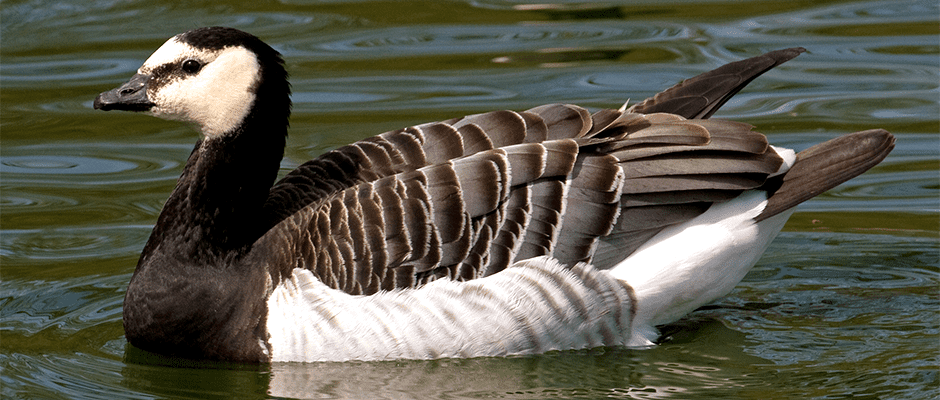

Rather than using their historical migratory stopovers, Barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) have begun making nonstop journeys from the Netherlands to their Arctic breeding grounds. Scientists say the reason is climate change.

In a study published in Current Biology, researchers tracked female barnacle geese traveling in the spring from the North Sea coast where they winter to the Russian Arctic where they nest. The birds had been known to use stopover sites along the Baltic and Barents seas along their migration journey. But with a warming climate, researchers were curious about how their journeys may be impacted.

“The climate is warming so rapidly in the Arctic, much more rapidly than anywhere else in the world,” said Bart Nolet, a professor at the University of Amsterdam and a researcher at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology who was senior author of the study. “This means the birds face difficulty in tracking those changes.”

Nolet and his colleagues already noted anecdotally that the birds stopped using a particular stopover site in the Baltic region in the past 20 to 25 years. That showed them that the birds are capable of changing their migrating behavior.

Nolet and his colleagues used GPS tracking, remote sensing, stable isotope techniques and field observations among the birds’ flyway. What they found surprised them.

With snow melting earlier in the Arctic, the team found the birds didn’t make long stopovers anymore. Instead, they sped up their journey from their wintering areas to the Arctic and migrated more or less nonstop, Nolet said. “Up to that moment, we thought they would need stopovers to fuel their migration and also bring enough body stores to the breeding grounds for eggs and incubation.”

As a result of this fast migration, the birds arrived in the Arctic earlier in the year when there wasn’t any snow. They then took about seven days to refuel after a long journey, but because of the timing, they can no longer take advantage of peak vegetation. As a result, Nolet said gosling survival tends to be low. When goslings hatch, the quality of the grass is already dropping, which is not so good for their growth, he said.

While this seems like bad news for the barnacle geese, Nolet said this isn’t the full story. “We just looked at survival of goslings in the summer and not the whole year-round,” he said, adding that there may be some compensation later on in the winter as they migrate to their wintering areas. Further, with fewer goslings migrating, he said there may be less competition later on in the season.

Nolet also noted some geese stopped migrating, likely due to habitat changes in their wintering areas. He plans to compare the migratory and nonmigratory groups to understand the costs and benefits of migration.

“The Arctic is warming rapidly, much more rapidly than other areas,” he said. “And Arctic migrating birds have trouble to keep up with the rapid changes. Some birds adjust to it and others may not. We’re just figuring out how they are dealing with this problem.”

Header Image: Barnacle geese forage after a long migration. Researchers found with a warming climate, the species is stopping less on their migration to their breeding grounds. ©Tony Hisgett