Share this article

Simpler rabies test a ‘game changer’ in remote spots

Rabies is a worldwide problem — a deadly disease affecting humans in much of the world and mostly wildlife in North America, but diagnosing it hasn’t been easy. It’s relied on lab work with expensive equipment in professional facilities, and that’s not a simple task for wildlife biologists in the field or doctors in rural areas.

But another test for rabies, called the DRIT, has recently been approved for worldwide use that will make it much easier to test for rabies in remote locations.

“This DRIT test was a game changer for wildlife rabies management,” said Richard Chipman, National Rabies Management Program Coordinator for USDA Wildlife Services, which provided thousands of samples that informed the approval.

The DRIT, or direct rapid immunohistochemical test, allows technicians to test for rabies using a light microscope and basic chemicals. Since 2005, Wildlife Services has tested over 90,000 samples and trained personnel in 21 states to administer the test.

In May, thanks in part to those samples, the general assembly of the World Association for Animal Health (OIE) approved the DRIT as an acceptable test for rabies diagnosis.

“It’s come a long way from us scratching our heads and saying, ‘No, this is crazy,’” said Charles Rupprecht, the former rabies chief for the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention who developed the test.

The DRIT requires a touch impression of brainstem tissue, 52 minutes of staining and a light microscope to look for magenta coloration within infected neurons that indicates a positive test. The standard rabies diagnostic procedure requires a fluorescent antibody test that can only be conducted in a laboratory.

“This test is based on sound diagnostic, scientific principles,” Rupprecht said. “The test should be thought of not just as confirmatory. Ideally it could and should be used as a primary test, after proper training.”

Among humans, rabies has the highest case fatality rate of any known disease, killing an average of one person every nine minutes globally, mostly children under the age of 15 who were bitten by an infected animal. In the United States, 91 percent of rabies cases are wild animals, mostly bats and raccoons with 5,000 to 6,000 positive cases diagnosed annually.

“We’re living in this sea of rabies,” Chipman said.

Wildlife Services is wading into that sea in an effort to stop the spread of rabies and gradually eliminate it. The $28 million NRMP targets rabies in wildlife by distributing more than 10 million baits containing oral vaccines from aircraft each year in an effort to reach animals in infected areas. The DRIT has helped find those infected areas, Chipman said, by allowing wildlife technicians to test suspected animals as soon as they turn up.

“We’ll always have rabies. We won’t be able to eradicate it,” Rupprecht said. But certain variants of it can be eliminated, he said, and having a simpler test can help make that happen.

Wildlife Services is a Strategic Partner of The Wildlife Society.

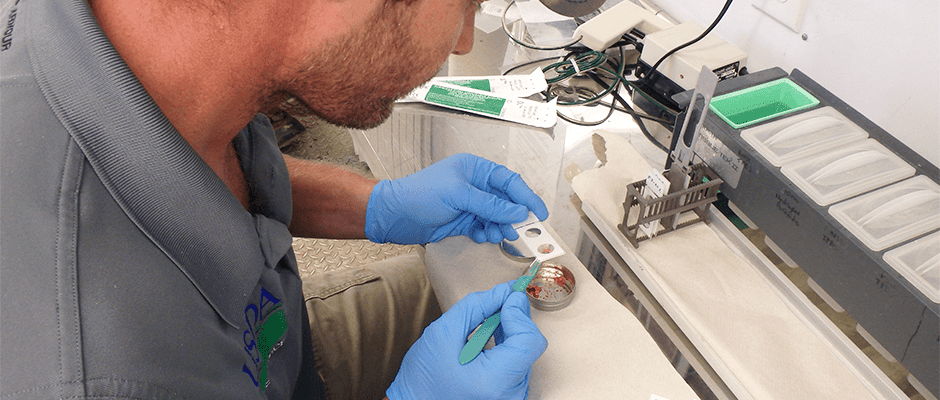

Header Image:

A wildlife technician checks a tissue sample for signs of rabies using DRIT. Wildlife Services has trained personnel in 21 states to administer this alternative rabies test that makes field diagnosis simpler.

©USDA Wildlife Services