Share this article

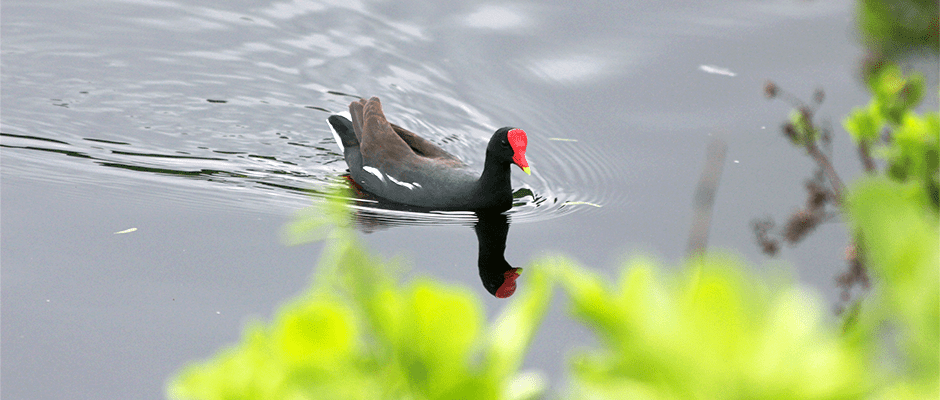

Hawaiian gallinules won’t leave home, putting them at risk

Endangered native Hawaiian waterbirds like the Hawaiian gallinule (Gallinula galeata sandvicensis) and the Hawaiian coot (Fulica alai) have benefited from habitat on national wildlife refuges and other protected wetlands, ultimately increasing from 60 gallinules and hundreds of coots in the early 1900s to 1,000 and 2,000 respectively today. But there’s still little known about the species’ genetics.

Researchers sought to change that in a study published in The Condor: Ornithological Applications. The team looked at the genetics of Hawaiian coots and gallinules with the purpose of answering questions about their genetic diversity and variation between islands and species.

“We really wanted to make sure we understood more about their genetics in order to help recover them,” said the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Jared Underwood, a co-author on the study.

Underwood and his colleagues analyzed mitochondrial and microsatellite markers from blood, tissue and feather samples for both species. They then used multiple analysis methods to look at differences in genetics.

“This was driven by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s recovery plan that says there should be populations of these species on most, if not all main Hawaiian islands he said. Right now, gallinules are found on only two Hawaiian Islands — Kauai and Oahu — but there are plans to reintroduce them elsewhere.

The team found for the gallinules, there was no gene mixing between the two island populations, which are about 100 miles apart. That stumped researchers.

“Gallinules are known to have quite the ability to move,” Underwood said. So why are they keeping to themselves?

Maybe the birds that have survived are the ones that stayed hidden in wetlands and didn’t move around, and this behavior has been perpetuated in the species, he speculated. Or maybe the population has not yet reached a level where the birds need to disperse to different islands.

However, the Hawaiian coot genetics showed the opposite.

“They retain the ability to move and they are mixing,” he said. “That bodes better for them as a species. If something does happen on one island, it won’t wipe out half of the genetic variability.”

In the past, Underwood said, hurricanes have contributed to extinction of other native Hawaiian bird species when they have small population sizes. The results of their study highlight the importance of creating additional populations, especially of gallinules, on other islands, he said. Managers may want to consider taking birds from both islands to preserve both genetic legacies.

“From a conservation standpoint, there’s a growing interest in trying to translocate the gallinule to additional islands,” Underwood said. “This is the next step in recovery for that species.”

Header Image: Hawaiian gallinules’ tendency to stay in one place puts the species at higher risk from events such as hurricanes. ©Jared Underwood