Share this article

Genetics study aims to aid pronghorn conservation decisions

Where highways have been identified as barriers to seasonal movements of migratory pronghorn, a project just beginning in Wyoming hopes to highlight the genetic effects of these anthropogenic stressors on the once-abundant species.

Melanie LaCava, a second-year Ph.D. student at the University of Wyoming, outlined this research project during the Student Research in Progress poster session at the TWS Annual Conference in Raleigh last October. The poster won first place in the Ph.D. category, and although the project is in its early stages, the research shows promise for informing conservation decisions.

“We know that highways are definitely barriers for seasonal movements. What I’m hoping do is provide information on whether they’re also acting as a genetic barrier,” LaCava said. “There have been two [wildlife highway overpasses] built in Wyoming recently and they’re looking to build more. What I’m hoping to provide is an extra layer of information to help inform decisions like that.”

Melanie LaCava collects a muscle sample from a harvested pronghorn at a Wyoming Game and Fish Department hunter check station. ©Adele Reinking

Pronghorn populations bottomed out around 13,000 individuals in 1915, but saw gradual recovery up until the ’80s. Today, Wyoming is estimated to harbor about 400,000 pronghorn, half of the species’ current population. Some genetic research has been done on pronghorn in Yellowstone National Park and in the southern portion of their range, but LaCava’s study will be the first to sample the entire genome.

LaCava, working with Dr. Holly Ernest and a team of researchers in the Wildlife Genomics and Disease Ecology Lab, as well as the Wyoming State Veterinary Lab and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, have collected over 1,000 DNA samples. They will compare tens of thousands of genetic markers across these samples, which will provide an incredible amount of statistical resolution to get at fine-scale genetic patterns. According to LaCava, this statistical power will allow the researchers to investigate genetic connectivity at the level of the individual instead of pre-assigning individuals to populations. This is advantageous for a wide-ranging species like pronghorn that may not naturally cluster into populations.

LaCava is currently preparing several rounds of samples for sequencing so she can begin processing the raw genetic data on a super computer at the University of Wyoming’s Advanced Research Computing Center. Once the DNA sequences are processed, LaCava will be able to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms throughout the pronghorn genome to develop metrics of genetic variation among individuals in the study. She can then incorporate landscape data, looking for areas of low genetic connectivity that may align with geographic features such as highways or mountain ranges.

“Our null hypothesis would be an isolation by distance model, where individuals that are geographically closer together would be more [genetically] similar,” LaCava said. Deviations from the null model might indicate a landscape feature is acting as a barrier to gene flow.

Because the methods she is using are so intricate, LaCava tested them during a “pilot” study last summer, which laid the groundwork for her poster in Raleigh. She says presenting was important for her to interact with researchers from different fields of research who could provide important feedback as the project continues to develop. She is honored to win first place in the poster session and grateful for the insight she received. She also hopes to return to the conference and present on the results of the study once it is completed.

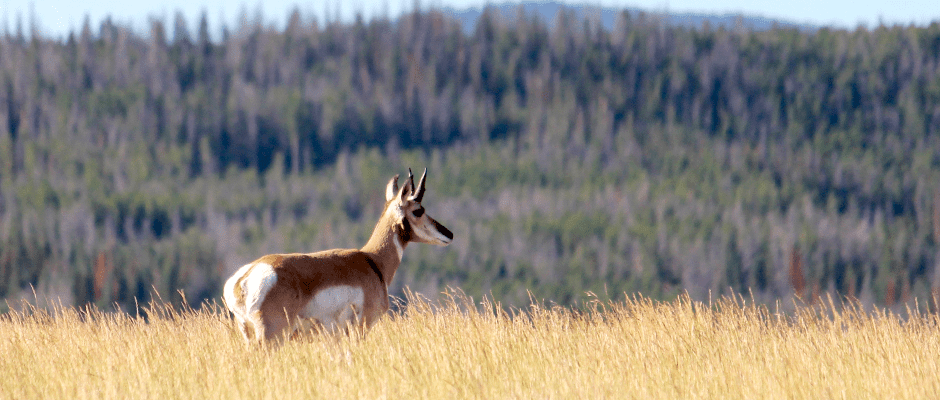

Header Image: A pronghorn buck in south-central Wyoming. ©Melanie LaCava