Share this article

For Yellowstone grizzlies, paths may lead out of isolation

When Yellowstone grizzlies lost their threatened status last June, advocates for the bears feared they were too isolated to sustain their populations without federal protections.

The grizzlies (Ursus arctos) are genetically isolated. The next nearest population resides in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, about 110 kilometers to the north, separated by mountain ranges; farm and ranchland; highways and urban areas including Helena, Butte and Bozeman, Montana.

But as the two populations grow and their ranges expand, the possibility of a northern male grizzly dispersing to the Yellowstone Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem becomes greater, raising hopes of more genetic mixing among Yellowstone grizzlies as well as fears of increased run-ins with humans along the way.

“I would not be surprised if we find evidence of a successful immigrant in the next couple of years,” said TWS member Frank van Manen, team leader for the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team and a coauthor on a paper in the Ecological Society of America’s open-access journal Ecosphere that mapped possible routes the bears could take.

By understanding the routes the bears might take, van Manen said, land managers can plan movement corridors, transportation officials can consider mitigating highway barriers in their way and communities can be ready to prevent grizzlies from appearing at trash cans and bird feeders.

“Bears are showing in places they haven’t been seen for 100 years,” said van Manen, a U.S. Geological Survey biologist whose team included researchers from the U.S.G.S.; Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks and Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

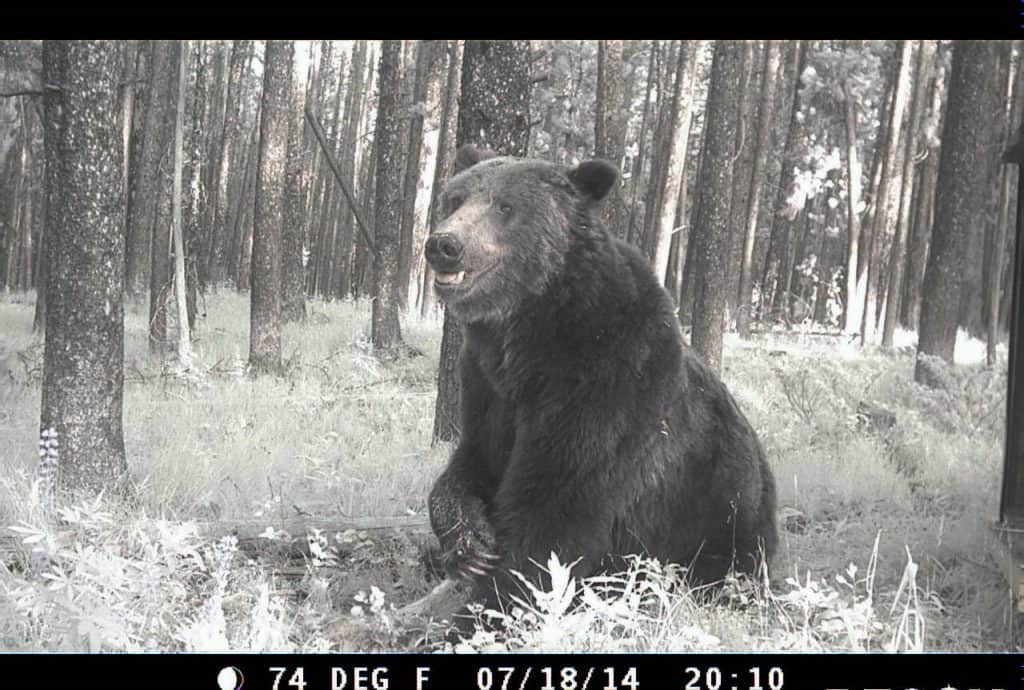

A remote camera documented this male grizzly bear in Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest in Montana, part of the Yellowstone Greater Ecosystem. Remote camera traps are one way to verify sightings of grizzly bears exploring new landscapes outside of the occupied range. ©USGS-IGBST

The team documented 21 instances of grizzlies outside their known occupied ranges, mostly from northern grizzlies dispersing toward Yellowstone. While they found no indication that a grizzly had ever crossed the entire distance from one ecosystem to another, the likelihood continues to grow, van Manen said. Male grizzlies typically disperse 30 to 40 kilometers — about one-third the distance between the two populations. But they have been known to travel as far as 170 kilometers, putting the two ecosystems within reach of a wide-ranging bear.

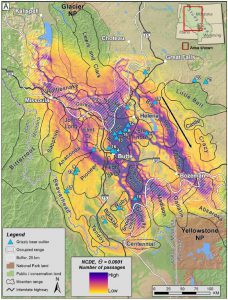

The team examined paths the bears would likely follow, based on an unusually rich dataset from the two ecosystems. Tracking collars on 124 male bears gave them hundreds of thousands of GPS locations showing how they move through their environments. Researchers combined that information with details about topography, streams and proximity to roads and homes to map out paths the bears would likely take, either through or around developed areas.

“We basically let the bears tell us where those paths would be,” van Manen said.

A map illustrates predicted paths for male grizzlies from the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

©Ecological Society of America

The bears also told them if they were right. Mapping the observations of confirmed bear sightings, they found the actual bear paths hewed close to their predictions.

“There was pretty remarkable agreement,” van Manen said.

Although they are isolated, the Yellowstone grizzlies aren’t in any immediate danger from a genetic standpoint, he said, but increased genetic diversity would give them greater resiliency to environmental conditions. Bears reaching from one ecosystem to another will probably be a rare event, van Manen said, but it won’t take many northern bears sharing their DNA to increase the Yellowstone population’s diversity.

“This might still take a little bit of time,” he said, “but as the populations are allowed to expand, that probability will likely increase over time.”

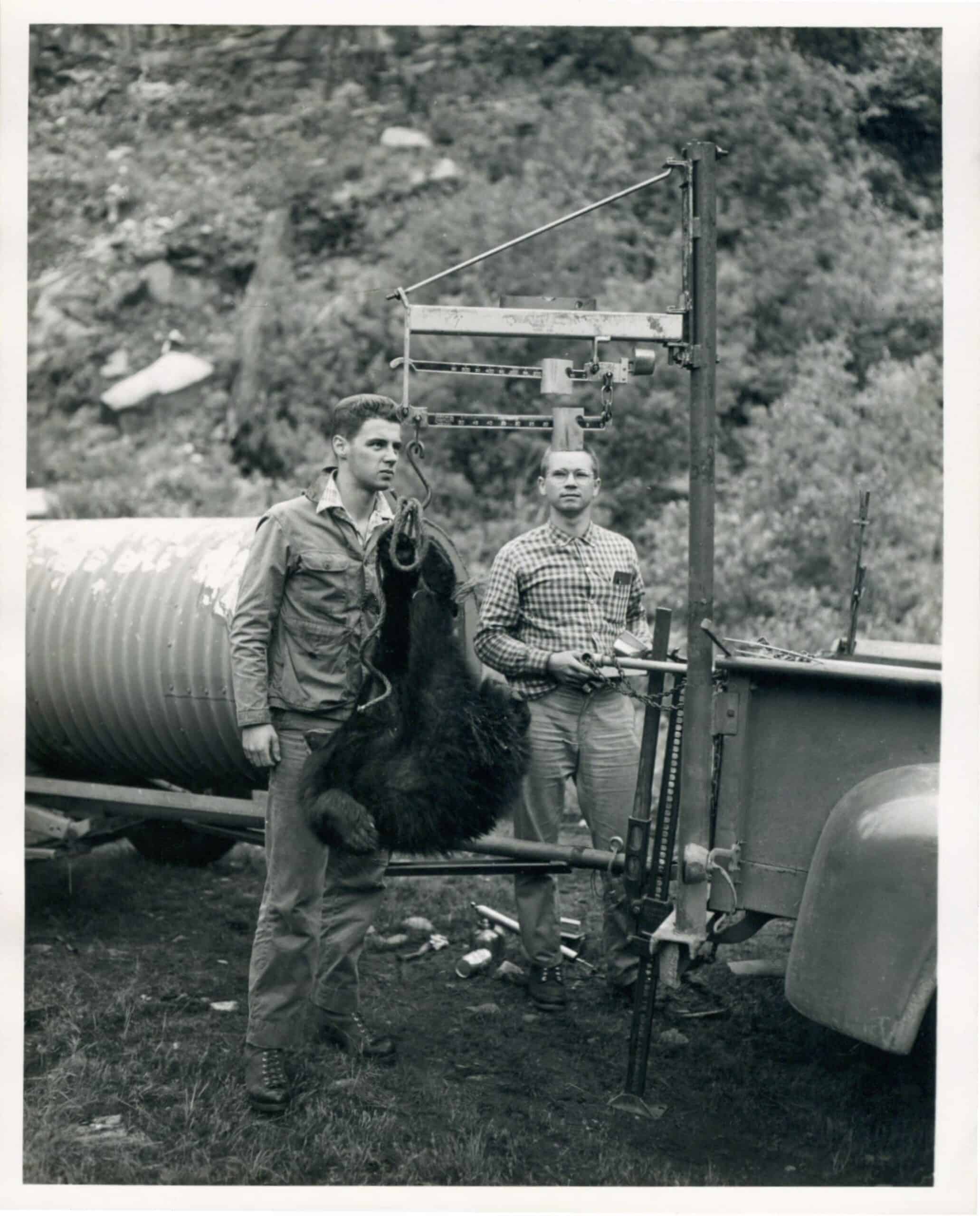

Header Image: Chad Dickinson, a biological science technician with the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, fits a Global Positioning System collar on a male grizzly bear in Yellowstone National Park. The team used GPS telemetry data from males like this one to map possible pathways that could unite these bears with populations to the north. ©Frank van Manen