Share this article

Birds at greater risk of hitting windows in rural areas

Nearly 1 billion birds in North America are estimated to die annually from striking windows or building exteriors, and researchers conducting a recent comprehensive study of the phenomenon found the threat is greater for birds in rural areas than it is for urban birds.

“If you take the same building and put it in a very urbanized area, the number of window collisions we found was lower,” said Stephen Hager, a biology professor at Augustana College in Illinois and lead author of the study published in Biological Conservation.

To conduct their study, researchers took advantage of the Ecological Research as Education Network, a program for large-scale ecological, collaborative projects. The network provides a model for collaborative ecological research that results in publishable data, involving undergraduate students and faculty members. About 150 students from 40 North American colleges and universities participated, Hager said, and while each student played a small role, “small roles can add up to a big, amazing project.”

Hager previously published research in 2013 assessing factors that influenced bird-window collisions in northwestern Illinois.

“After the paper was published, we wanted to assess bird window collisions at a broader, continental scale,” he said.

To do this, Hager and his colleagues monitored bird mortality at almost 300 buildings on college and university campuses in North America. The buildings were a variety of sizes and surrounded by different types of landscapes.

Collaborators across the continent counted dead birds around buildings and took note of how much vegetation, including trees and grass, were in the area, and how close sidewalks and structures were. They also measured the number and area of the windows on the buildings.

Because there were so many collaborators, Hager said it was important to standardize the way the students collected data, so professors supervised their students to make sure they followed the same protocols.

After compiling the research, Hager and his colleagues found that as building size increases, window collisions increase. That was important, Hager said, but it wasn’t surprising. His previous research found the same correlation.

What he didn’t expect to find was that these collisions were more likely in less developed areas. Researchers aren’t sure why this is the case, but they have a few hypotheses they hope to test. One is that when birds migrate, they prefer to fly in less developed areas. Another is that birds in urban areas may develop learned behavior to avoid hitting windows that those in rural areas don’t.

Hager and his colleagues suggest implementing “Lights Out” programs at large buildings in all landscapes, ranging from low to high development, so that birds may avoid collisions at the riskiest types of buildings. Lights Out programs, promoted by the National Audubon Society, include turning out lights in buildings so that migrating birds flying overhead are not attracted to lighted windows.

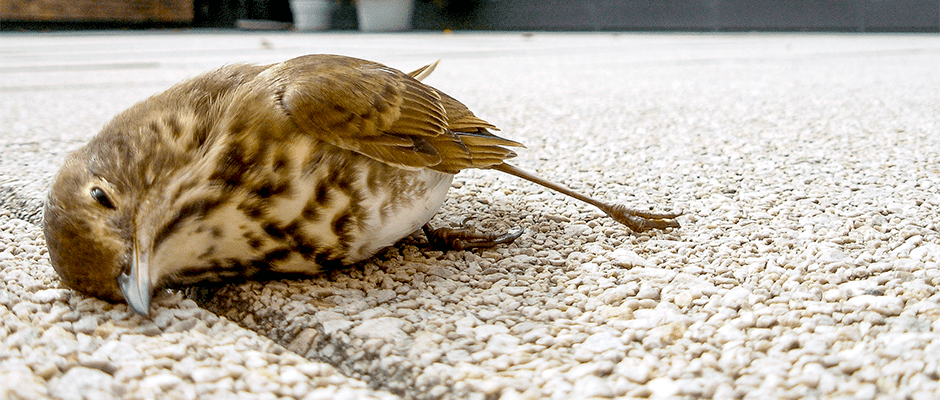

Header Image: Researchers monitored bird mortalities such as this hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus) at a campus building in Augustana College outside of buildings and found collisions with windows were more common on large buildings in rural areas than in urban areas. ©Stephen Hager