Share this article

Algae and warming water could be killing Michigan waterfowl

Since the late 1990s, an increasing number of waterfowl have been dropping and drowning in the Great Lakes due to more frequent botulism outbreaks. Biologists recently found evidence that warming waters and greater amounts of algae could be driving the bird die-offs by creating more favorable conditions for toxic botulism bacteria to proliferate.

Botulism poisons and paralyzes birds by infecting their food resources, just as it affects humans. Records dating back to the 1960s document the bacterial disease killing off thousands of waterfowl over the summer and fall in the Great Lakes region. But Karine Princé, lead author on the paper published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, wanted to figure out why the deaths became more widespread in recent decades.

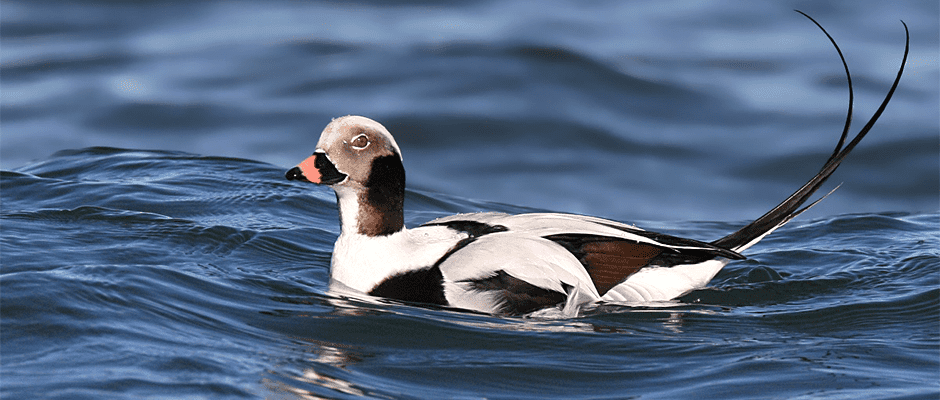

A University of Wisconsin-Madison postdoctoral research associate, she and her colleagues analyzed a United States Geological Survey citizen science database of waterfowl botulism mortality, examining counts of beached carcasses and sick birds in northern Lake Michigan from 2010 to 2013. Commonly afflicted species included the common loon (Gavia immer), red-breasted merganser (Mergus serrator), long-tailed duck (Clangula hyemalis), herring gull (Larus argentatus), ring-billed gull (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae), double-crested cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus), red-necked grebe (Podiceps grisegena) and white-winged scoter (Melanitta deglandi).

Using satellite data on lake surface temperature and chlorophyll concentration as an indication of the prevalence of green algae, the researchers looked for a link between the mortality events and fluctuating environmental factors.

There was a “synchrony,” they found, between die-off spikes and occurrences of warmer waters and higher algal production. The team thinks aquatic environments are becoming increasingly oxygen-depleted and favorable for botulism bacteria as climate change raises water temperatures and invasive zebra mussels intensify the growth of algae by filtering the water and letting through more sunlight.

“Seasonal fluctuations in lake surface temperature and chlorophyll concentration were important in the spread of avian botulism,” Princé said.

Through shedding light on the conditions correlated with peaks in botulism deaths, the scientists said, the study could allow bird monitoring programs to track lake water temperature and chlorophyll levels to predict and proactively respond to worsening outbreaks. They believe citizen science initiatives will remain crucial to this mission.

“We got important information from this citizen science program,” Princé said. “Volunteer citizens help gather data at large spatial and temporal scales, which could not be achieved using a classic research experiment.”

Header Image: A long-tailed duck swims on Long Island, New York. ©Wolfgang Wander