Share this article

WSB study: Wing swabs can help identify threatened bat species

As white-nose syndrome devastates bats across the continent, scientists are scrambling to better research and conserve them. Biologists in western Canada recently discovered they could use wing swabs for noninvasive genetic sampling and species identification in bats, which is vital to understanding their ecology and protecting the caves where they hibernate.

“We’re trying to find what species are using these underground environments, which will help managers decide what level of protection needs to be applied to these habitats,” said Cori Lausen, co-author on the study in Wildlife Society Bulletin. “Swabbing the inside of the wing and getting epithelial cells is a great way to identify the species of bat.”

Some species look so similar in the field, she said, that “it’s almost impossible to tell them apart.” The Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis) and little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) are two such bats that roost together and require genetic testing to be distinguished from each other. Despite their morphological likeness, only the little brown myotis is federally listed as endangered. It has a single breeding population that’s now decimated in the eastern part of Canada by the white-nose fungus, and the die-off is expected to continue as the disease proliferates westward, where the species is still fungus-free and abundant.

“It became important to tell these species apart at the hibernaculum because according to species-at-risk legislation in this country, any place a little brown is hibernating is critical habitat and takes on a level of protection,” said Lausen, a bat specialist with the Wildlife Conservation Society-Canada.

She and her colleagues tested swabs as a less harmful alternative to biopsy punches, which leave holes where they extract wing tissue to identify species through DNA analysis. These wounds don’t heal for bats going into hibernation since their bodies focus their resources on conserving energy over winter, so the animals might suffer long-term because of the persisting damage.

In 2014 and 2015, Lausen’s team lightly rubbed swabs across the wings of 55 already identified bats captured in nets across northern Alberta and British Columbia during summer and fall. The researchers gathered a lot of genetic material in the form of outer skin cells that they then sent to the lab to determine the various species the DNA had come from. All species identifications from swabs taken inside the wing — Yuma myotis, little brown myotis, northern myotis (Myotis septentrionalis), long-eared myotis (Myotis evotis) and silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans) — were correct, said Lausen, a TWS member.

While testing for white-nose syndrome during wintertime in the eastern United States, she said, scientists from Northern Arizona University also found they could use wing swabs to acquire DNA and identify bat species last year. Wing swabs are a better way to genetically sample bats in hibernacula than the guano used in other circumstances, she said, because bats don’t excrete while hibernating. Wing swabs are also less disturbing and easier to obtain than rougher swabs biologists have long used to collect cells inside bats’ cheeks, where the animals can chew, clamp down on or swallow the tool.

“This is good timing for people to realize this technique is dual-purpose sampling,” Lausen said. “People are swabbing bats for the white-nose fungus in hibernacula. If they push a little harder, they’ll get DNA. That opens the opportunity not just to tell what species you have, but also to do population genetics studies.”

Lausen and her fellow researchers are working with other biologists and cavers trained to handle bats to take wing swabs in fall and winter, facilitating the discovery of new hibernacula and the species inhabiting them.

“Every data point we get in the West is golden because we don’t know much about our bats, especially what their species need for hibernation,” Lausen said.

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper in the September issue of Wildlife Society Bulletin. Go to Publications and then Wildlife Society Bulletin.

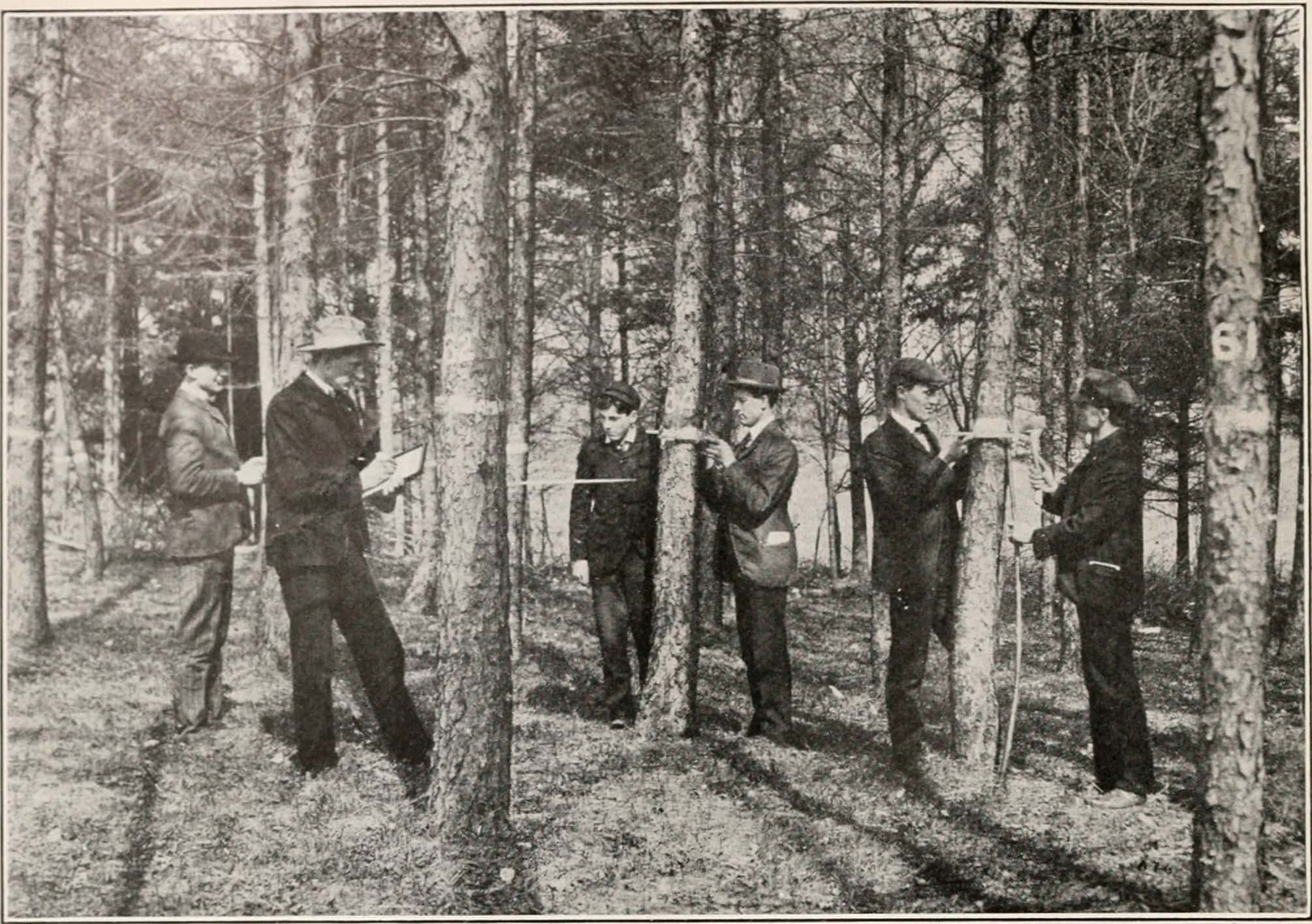

Header Image: A researcher gently runs a swab across a little brown myotis’ wing. ©Jared Hobbs